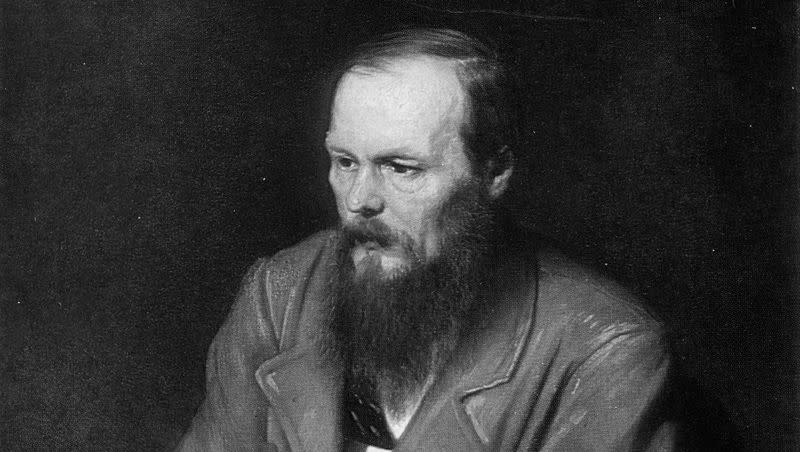

Perspective: What Dostoevsky can teach us about suffering and faith

- Oops!Something went wrong.Please try again later.

- Oops!Something went wrong.Please try again later.

In August 1867, at a museum in Basel, Switzerland, the Russian writer Fyodor Dostoevsky found himself standing before a painting of Christ, unable to look away.

The work, entitled “The Body of the Dead Christ in the Tomb” and painted by Hans Holbein, depicts the disfigured reality of Christ’s mortal frame after the crucifixion.

Dostoevsky’s second wife, Anna Grigorievna, wrote that the painting “portrays Jesus Christ, who has suffered inhuman torture. ... His swollen face is covered with bloody wounds, and he looks terrible.”

She described her husband’s reaction: “The painting made an overwhelming impression on my husband, and he stood before it as if dumbstruck.” This experience later bled into Dostoevsky’s work when he wrote “The Idiot,” which was published in serialized form.

That novel, in many ways, explores a central question that relates to Holbein’s shocking painting: How do we reconcile Christ’s literal resurrection with the brutal reality of his death? It is a question many Christians around the world may ponder this weekend as they journey from the sorrow of Good Friday into the glory and triumph of Christ’s Easter resurrection.

Whether consciously or not, Dostoevsky answers the question through the novel’s protagonist, Prince Myshkin. The prince, known as an “idiot” for his epileptic seizures and his innocent child-like view of the world, was Dostoevsky’s creation of a “perfectly beautiful man,” one who spoke the now-famous phrase “Beauty will save the world.” Dostoevsky’s prince was someone who embraced and loved the world all while perfectly knowing its darkness.

In creating such a character, Dostoevsky inevitably made a literary mirror of Christ, the Prince of Peace. Paradoxically, however, in creating his fictional prince, Dostoevsky drew from the mundane realities of his own life.

For example, Prince Myshkin, like Dostoevsky, also traveled to Basel and saw the original Holbein painting of Christ. In the novel, while discussing the painting, another character asks Myshkin, “Do you believe in God?”

The question repeats: what value, what beauty, could ever come from something so lowly as this crucified Christ?

Myshkin replies, “A man could … lose his faith from that painting!” Continuing on, he does not answer the question directly, but instead tells a story of a woman he once saw with her 6-week-old baby.

He recounts seeing the infant smile up at the mother. After this, she made the sign of the cross with great piety, and Myshkin asked why.

“It’s just that a mother rejoices,” she said, “when she notices her baby’s first smile, the same as God rejoices each time he looks down from heaven and sees a sinner standing before him and praying with all his heart.”

Related

Of the many personal attributes Dostoevsky gave to the fictional Myshkin, the most autobiographical was his deep and sincere love for children. At the beginning of the novel, Myshkin speaks to a group of children, talking with them as if adults, holding their opinion in high esteem. He hides nothing from them and lets them “come unto him,” entrusting to them, as Christ would, the full truth of anything he had to say, noting that “a child can give extremely important advice even in the most difficult matters.”

Myshkin’s love for children becomes all the more profound when Dostoevsky’s infant daughter passes away only five months after the novel began its serial publication.

His grief is as painful to behold as the visage of Holbein’s Christ: “This little three-month-old creature, so poor, so tiny, was already a person and a character for me. She was beginning to know me, to love, and smile when I came near. ... And now they say to me in consolation that I’ll have other children. But where is Sonya? Where is this little personality for whom, I say boldly, I would accept the cross’s agony if only she might be alive?”

The most famous story of the novel also comes from Myshkin, who tells of a man “led to a scaffold, along with others, and a sentence of death by firing squad was read out to him, for a political crime.” Twenty minutes pass after the man hears his final sentence when a pardon is given to save his life. Myshkin says for “a quarter of an hour at the least, (he) lived under the certain conviction that in a few minutes he would suddenly die.”

Like the stories cited above, Myshkin’s tale comes directly from Dostoevsky’s life. Before Dostoevsky began his literary career, he was sentenced to die before a firing squad for a political crime, only to be pardoned moments before his execution.

In that moment of imminent death, Dostoevsky drew on his faith in Christ to save him. The records state that as Dostoevsky awaited his execution, he turned to his peers and said: “We will be together with Christ.” And from this moment of intense beauty, inches from death, sprang the well of light that is the work of Dostoevsky.

That beauty, the beauty in Christ, not only saves Dostoevsky, but will, as Myshkin prophesied, save the world. For Dostoevsky, faith in Christ, even with Christ in the most lowly of forms (as he is depicted in the Holbein painting, and as he was on Good Friday), is the only answer to the woes of life: to the inexplicable suffering or death of a child, to the ravages of war, even to facing one’s own imminent execution.

We live in a world that often feels like Holbein’s Christ, dead and dying still; a world full of wars and rumors of wars, where the hearts of men continue to fail them day and night. We currently live under the real threat of nuclear war, as Dostoevsky before the firing squad. We stand before this world as Dostoevsky before the dead Christ, “as if dumbstruck.” Yet beyond the dark chaos there is light — and that light is Christ, the one who overcame this world.

No matter the human torture that was forced upon Christ, or however we try to limit Him with our words, our poetry, even our painting, he is still the light of the world. Whether wrapped in swaddling clothes, hanging on the cross or descending in robes of crimson, Christ is the King of Kings, and the hope of the world — the beauty that will save the world.

Scott Raines is a writer and doctoral student at the University of Kansas.