Perspective: The dressing down of America

U.S. Sen. John Fetterman of Pennsylvania recently returned to the Senate after treatment for clinical depression. While his endeavor to seek help is commendable, his appearance upon his return was disgraceful.

Fetterman stepped out of his car and greeted onlookers in workout shorts, gray sneakers and a baggy Carhartt sweatshirt. His look, or lack thereof, caused an uproar on social media. And rightfully so.

Saagar Enjeti, a co-host of the podcast “Breaking Points” who has long been critical of Fetterman’s indecorous appearance, tweeted “no words.” For what else could anyone say?

no words https://t.co/4bqpQvMa1I

— Saagar Enjeti (@esaagar) April 18, 2023

But Enjeti went on to write, “People who buck proper dress code at the highest levels of public service are narcissists who think their personal comfort/‘brand’ supersedes decorum. They’re not trying to relate, they think they’re above everyone else.”

It’s true that dressing down is part of Fetterman’s brand, and it might play better in some parts of the country than in others. In The Washington Post, Kara Voght writes that the “comfort-craving Fetterman” tries to embody a kind of anti-fashion which “bolstered his everyman image during his successful run for office last year.”

It made national news when he wore a suit and tie on his first day in the Senate. As a candidate, he welcomed President Joe Biden to Pittsburgh while wearing shorts.

Coming back from treatment for depression, as Voght writes, “the question of what the senator should wear was part of a larger challenge, which is reintroducing Sen. John Fetterman to Washington — on his own terms.” And therein lies the problem — the focus on his own interests and desires and not his role as a public servant.

Sadly, however, Fetterman’s attire reflects our broader culture of unkempt appearance and dress. We act as if dress isn’t important. But what we wear isn’t simply a matter of decorum; rather, it reflects one’s heart and metaphysical well-being. How one dresses the body mirrors the soundness of the soul and the mind, and signals respect for both the beauty of the world and those who live in it.

And in Washington, in particular, dignified dress reflects the order, virtue and beauty of our democracy, as well as the dignity of those our elected officials represent.

Related

The importance of dress is something I learned from my maternal grandfather. Though he passed before I was born, his character continues to influence me. While growing up, my mother frequently relayed one of his favorite phrases: “You can never overdress, but you can always underdress.”

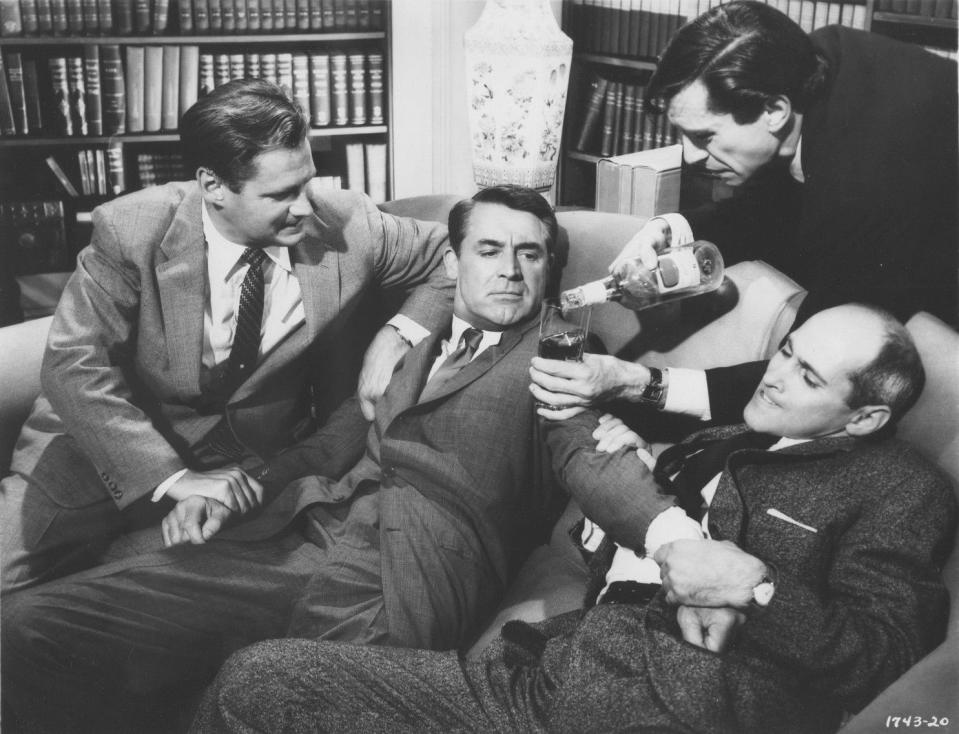

The idea reflects the now-lost culture my grandfather knew, a time when almost all men dressed in suit and tie for every social exchange. Consider, as one small example, Alfred Hitchcock’s 1959 film “North by Northwest.” Every scene features men dressed in suit and tie as a normal part of everyday life. For a man today, such dress constitutes attire only for the year’s most important occasions (if that): weddings, church services or, supposedly, the dress of a public servant. (And the attire at many church services, it must be noted, has become distressingly informal.)

My grandfather’s aphorism would hardly be intelligible to many of today’s men and women. In fact, the mentality has inverted to “less is best.” Comfort is king.

I see the cultural inversion in my university students who come to class looking like models in a Hanes underwear commercial. Rarely do I see a student well dressed and put together, having made the morning sacrifice to dress as if he or she had some sense of personal self-worth. Most students are content to show up and feel “comfy” — the anthem of contemporary fashion.

Writer Esmé Partridge says the decline in contemporary style is commonly accepted as “going goblin mode,” saying that “teenagers today are doing away with all ideals.”

“They like their celebrities upholding hardly any standards at all — celebrities like Billie Eilish who sport baggy clothes, tired eyes and an almost aggressively anti-sexual demeanor. A truly post-modern celebrity, Billie Eilish goes against the ‘grand narratives’ of the pop music industry. Even if she is right to do so, what her fame represents is clear: the latest form of anti-Platonism, fit for the 21st century.”

Ironically, Partridge’s essay coincided with a fashion line introduced by Ralph Lauren, wherein the company partnered with Morehouse and Spelman, traditionally Black colleges, on “a capsule collection inspired by the unique style of students who attended these institutions and others like them from the 1920s to 1950s.”

The clothes are sophisticated and refined, regal and royal. The dress of these student-models reflects sacrifices made to attain education, to better the world and to make their surroundings more beautiful. They reflect responsibility, personal dignity and hope for the future, not a state of self-destructive degeneracy into goblin mode.

Ralph Lauren unveils HBCU collection exclusively for Morehouse, Spelman College https://t.co/oltYBa5sX6 pic.twitter.com/QjqoFV8hDv

— philip lewis (@Phil_Lewis_) March 15, 2022

Our clothes are a measure of our cultural health, and we are ill as a society. Even our elected officials are now showing it to us plainly.

The philosopher Roger Scruton wrote that of the many problems of modernity, there is “a desire to spoil beauty in acts of aesthetic iconoclasm. Wherever beauty lies in wait for us, the desire to pre-empt its appeal can intervene, ensuring that its still small voice will not be heard behind the scenes of desecration. For beauty makes a claim on us: it is a call to renounce our narcissism and look with reverence on the world.”

That claim of beauty is a moral responsibility for ourselves, and for our neighbors. For a U.S. senator, it is the claim of the virtue and intrinsic value of those whom he represents. Whether intentional or not, Fetterman’s dress signals to the world that he cares nothing for the ideals of our national legislative bodies, let alone the people they represent.

The days of the 1920s and 1950s — the days of my grandfather — with men and women in respectful every-day dress are gone, but not lost. While we’ve traded those days for a society of sweats, we can still regain the ethos of “overdressing over underdressing.”

Scruton said that “beauty is vanishing from our world because we live as though it did not matter; and we live that way because we have lost the habit of sacrifice and are striving always to avoid it.”

Will we continue to allow ourselves, and our public officials, to avoid this duty for the fake-sake of comfort? Or will we stand and sacrifice and work to further beautify our world?

Scott Raines is a writer and doctoral student at the University of Kansas.