Perspective: The ‘God-sized hole’ in the American university

Fifty-one percent of Americans believe that “public colleges should stop offering degree programs that lead to low-paying jobs,” and 40% say that students in these programs shouldn’t receive federal financial aid, according to a recent report.

Among the degrees listed as most culpable in “wasting students’ money” were gender studies, art history, religious studies and ethnic studies.

Interestingly, the survey found “no notable differences” between Republicans and Democrats in how they responded to these questions.

When I shared these statistics, a friend who teaches at a well-known university in the Midwest, laughed and said, “Is it really only 51%? You sure it’s not higher?”

He added, “College is so expensive, you can’t just expect these kids to accrue that much debt in exchange for little to no practical skills.”

My friend is right, of course. Average tuition costs for four-year public universities in the U.S. have risen a staggering 23 times since 1963, while the national inflation rate has risen just under nine times. This means that if a school’s annual tuition cost $1,000 in 1963, it would now, on average, cost $23,000. With this kind of increase in tuition alone, one must seriously question the utility of any degree at all before enrolling.

The purpose of a university

The university, however, hasn’t always been merely a pathway for getting a job.

In an interview, Jessica Hooten Wilson, the Fletcher Jones Endowed Chair of Great Books at Pepperdine University, told me that “people have forgotten the purpose of the university system.”

She explained that universities have unfortunately been conflated with the utilitarianism of public school, but they were once “about wisdom and the liberal arts.”

“They were about creating theologians and creating schoolteachers. We think of colleges as a place holder, as a step you have to take, but that’s not how the university system should be.”

She continued, explaining that “universities are supposed to be the places where you increase knowledge in the world: What can we know about human beings in the humanities? What can we know about God with theology? What can we know about the world via science? And if we don’t have those enterprises creating and discovering knowledge for us, the whole society loses out, and not just the university.”

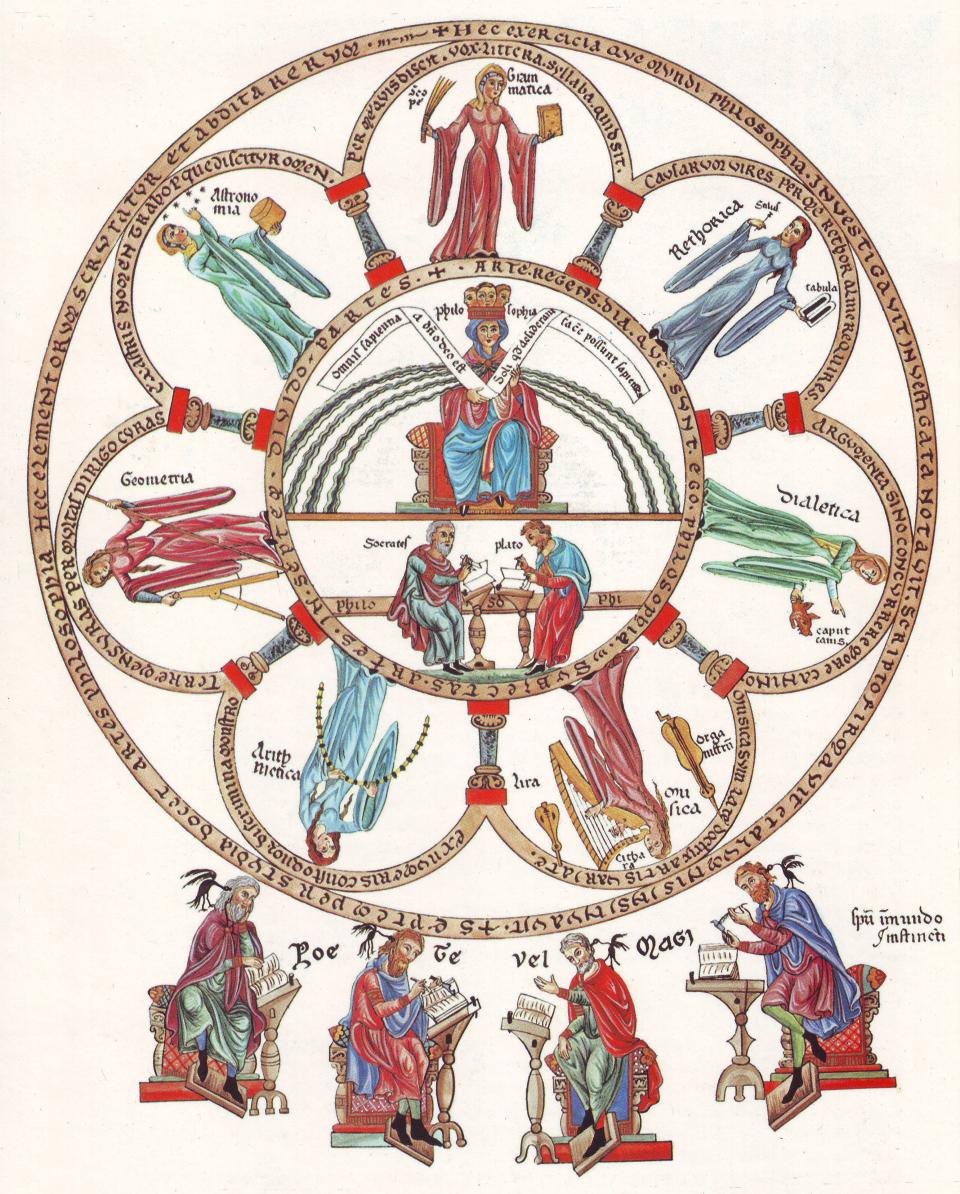

Her comments harken back to the founding of the medieval universities in Europe and their grounding in what were once called the seven liberal arts.

Related

How religious universities can help restore the broken promise of American education

Perspective: How universities can build the next generation of interfaith leaders

Described first by Plato in “The Republic,” the first four arts (or skills), called the Quadrivium, consisted in the study of arithmetic, music, geometry and astronomy. The other three, called the Trivium, were grammar, rhetoric and logic.

These seven disciplines were called the liberal arts because only one who is free from labor and work (“liber” meaning free in Latin, from which we get, for example, “liberated,” meaning “freed”) could have the free time to study them.

This meant that strictly nobles and upperclassmen — those who need never care about the field or the plow for their food — had time to dedicate to these finer or more refining arts and skills.

The liberal arts became the basic curriculum of study for the first universities in Europe and led the student to deeper knowledge and wisdom (philosophy), ultimately converging at the highest form of knowledge in better understanding God (theology).

Hooten Wilson said that “the Trivium and Quadrivium were primarily those practices or arts that enabled one to be able to think and to cultivate one’s soul — not just in times of crisis, avoiding despair by knowing one has a soul, but also in civil engagement.

The students, then, “were thus able to think transcendentally, to think eternally, even to think prophetically in order to create the institutions and policies and laws and literature that would help continue a free society. And all of these things are lost if we lose the liberal arts.”

She added, “a society that decides to embrace liberty needs the practices of the liberal arts because the liberal arts form free souls.”

A place to find God

Hooten Wilson’s talk of transcendence, eternity and the soul reflects the sacro-secular nature of what the university once was. In a sense, the university was a humanist temple of knowledge, intimately tied to the Catholic Church in medieval times and other Christian denominations in colonial America. The university was seen as almost a holy place in which one was symbolically “reborn” and “fed” from their “alma mater,” a Latin phrase for “nourishing mother.”

It was a place beyond money and mere utility. It was a place to find intellectual and spiritual gold, a place to find wisdom and a place to find God.

This religious grounding of the university gave (and in some cases continues to give) the institution a transcendent meaning far beyond “what kind of job are you looking for after college?” or “how much money are you going to make when you’re done?”

It was a place beyond money and mere utility. It was a place to find intellectual and spiritual gold, a place to find wisdom and a place to find God.

Universities and colleges have changed considerably since their founding in both medieval times and early America, as has the broader social understanding of what constitutes useful knowledge and study.

With the rationalist influence of Enlightenment philosophers, the purpose of knowledge and the university curriculum as a means to form and transform the soul, or even to draw nearer to God, slowly morphed into knowledge for knowledge’s sake. This left a soul-sized — or, we might say a God-sized — hole at the center of the university — one that we have yet to fill.

This centuries-long change in values from seeking transcendent knowledge and developing the soul, to values based merely on “useful” information exchanged for monetary gain, has slowly stripped the university of one of its primary sources of meaning. This is now reflected, somewhat ironically, in a general disapproval of the liberal arts.

Missing God in modern universities

I spoke about the university’s God-sized hole with a friend who is a business professor at the University of Kansas, where I teach. While talking, I mentioned the university logo. He was quite surprised to learn that the logo contains an image of Moses and the burning bush. Surrounding the image is Exodus 3:3 in Latin which reads: “I will now see this great sight, why the bush does not burn.”

The religious imagery at the University of Kansas, however, will likely change in the coming years. Many university and university press logos have shifted away from similar religious symbolism (symbolism based on the ideals of the liberal arts and religious foundings) to a vague blend of AI and the unbearably boring. Oxford University Press recently eliminated the Latin phrase Dominus iluminatio mea, or “The Lord is my light,” from its logo for a spiral staircase leading to nothing at all. It is a soulless sign for an ever growing soulless curriculum.

As the fundamental ideals of the university continue to slip from their origins, the question begins to steer away from “what’s the point of a gender studies course?” to “what’s the point of a $120,000 MBA,” or “why pay to study computer science when you can do so for nearly free online?”

The survey is already proving more prescient than simple public opinion. West Virginia University recently cut all language and linguistics degrees and faculty, and is proposing to cut nearly 30 more programs, eliminating 160 faculty positions. While the headlines highlight cuts to puppetry and other “useless” majors, the fine text shows that other disciplines, including civil engineering and education administration, among others, are on the chopping block.

In their book “Permanent Crisis: The Humanities in a Disenchanted Age,” Paul Reitter and Chad Wellmon argue that the humanities form a means to “compensate for deficits of modern life.” They write that “modernity destroys the humanities, but only the humanities can redeem modernity, a circular story of salvation.”

One of the great problems of modernity, however, is the general lack of belief in God. The German philosopher Friedrich Nietzsche famously wrote “God is dead. … And we have killed him. How shall we comfort ourselves, the murderers of all murderers?”

This was not a cause for celebration, but a call of emergency. For what will we do, Nietzsche asked, without God as the bedrock of social life and stability? “What festivals of atonement, what sacred games shall we have to invent? Is not the greatness of this deed too great for us?”

A similar question must be asked of the university. How shall we find nourishment if our alma mater only seeks money, and our students only seek high-paying jobs? How can we gain knowledge and wisdom as a society when we are only seeking content and computations? Where is the soul in all of this? Will we be able to fill a God-sized hole with an infinite stream of funding and endowments?

Professor Hooten Wilson, along with professors Roosevelt Montás, Zena Hitz and Jonathan Tram will wrestle with some of these questions in New York on Sept. 28 at the launch of the book “The Liberating Arts: Why We Need Liberal Arts Education.”

We need the liberal arts in their truest sense: We need the wisdom; we need the nourishment of the soul; we need God.

Scott Raines is a writer and doctoral student at the University of Kansas.