Perspective: How impeachment lost its power

- Oops!Something went wrong.Please try again later.

- Oops!Something went wrong.Please try again later.

- Oops!Something went wrong.Please try again later.

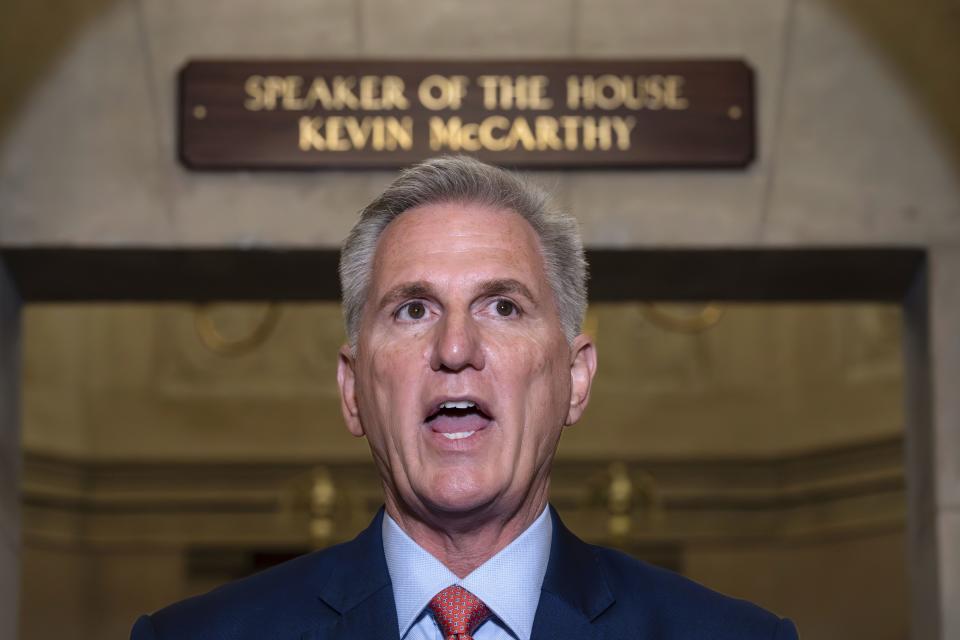

New York Times columnist David French has written an excellent article excoriating House Speaker Kevin McCarthy — and Republicans more broadly — for hypocrisy and for “dangerous escalation of American political combat” by opening an impeachment inquiry without clear evidence of “profound misconduct.”

In other words, for using their power for a “fishing expedition.”

French is largely correct. But in my view, he misses one thing: In the sense that most ordinary people think of these things, none of this really matters.

I don’t mean that impeachment will have no effect on coming elections. It clearly will have at least some effect, although it may not have the effect McCarthy expects. Nor do I mean that the degeneration of the use of impeachment as a political tool will not negatively affect our politics in the long run. It will.

And it will, of course, have immediate political effects within Congress. It may even save McCarthy’s speakership from radicals in his own party that want to dethrone him.

But as a tool for punishing or removing an out-of-control president, this exercise could not be more meaningless. President Joe Biden has as close to zero chance of being removed from office as you can get, and every player in Washington knows it.

I could cite to you the fact that several Republican senators have already thrown cold water on this inquiry, and given that Democrats essentially have 51 votes against impeachment already, there is a greater likelihood of two-thirds voting against conviction than the constitutionally required two-thirds voting for it.

Or I could cite the fact that McCarthy hasn’t even held a vote on this in the full House, which is not required but has traditionally been done, and he’s not doing this, in large part, because he almost certainly does not have the votes, even among his own troops in the House.

But that isn’t really the issue either.

The real issue is that the constitutional provision for controlling an out-of-control, unethical or lawbreaking president is broken. It was broken before McCarthy launched this inquiry. Impeachment and removal no longer present a serious threat to a president’s continuation in office. We’ve seen this repeatedly.

There have been four presidents who have faced removal from office vis-a-vis impeachment. The very old example of Andrew Johnson is the odd man out. He was impeached in the aftermath of the Civil War, over complicated issues concerning power over his own cabinet, exacerbated by partisanship. He survived conviction in the Senate by one vote.

Richard Nixon resigned rather than face an impeachment vote he knew he was going to lose, and a trial in the Senate that former presidential nominee Barry Goldwater, a member of Nixon’s own party, assured Nixon would convict him. But since then, things have changed.

Bill Clinton was impeached for obstruction of justice and perjury but not removed. Not even a majority of the Senate voted to remove him. Donald Trump was impeached twice, once for quid pro quo’s with a foreign power to help his own campaign, and then for the acts leading up to the attack on the Capitol on Jan. 6, 2021. In neither case was he convicted, although a bare majority voted to remove him in the second impeachment.

Since Nixon, the pattern is clear: The vast majority of partisans in the House will vote to impeach “the other guy,” and the vast majority of partisans in the Senate will not vote to remove “their guy” from office.

Related

Perspective: From Clinton to Trump, James Dobson was right about our moral tailspin

Opinion: Will Biden face impeachment if we avoid a government shutdown?

In the case of Nixon, the idea of civic duty beyond partisanship, an “important trust” given to the Senate, as the Federalist Papers put it, mattered to many Republican senators, particularly Goldwater, who told Nixon he’d personally vote to convict.

But the opposite happened in the cases of Clinton and Trump, cases in which the facts were, in large part, not disputed.

In 2021, most partisans, with the notable exception of Mitt Romney (who voted for both Trump impeachments) and a few other Republican senators (only one of whom faced voters in 2022), were simply not willing to anger their voters by removing another member of their party from office. It wasn’t really more complicated than that. The important trust given to the Senate was not a paramount concern. At least, not if it was bad for the next election.

McCarthy knows this. As does every Democrat expressing outrage at McCarthy’s inquiry.

In this current environment, it is clear that impeachment, no matter how disturbing the facts, is not a serious threat to remove a rogue president from office, nor bar him from holding office in the future. Thus, it is free to be used as simply a tool to make interesting political theater. Impeachment is only happening now because nobody is really taking this seriously. Everybody knows Biden won’t be removed.

So in a sense, French and others are correct that this is a fishing expedition and is lowering the bar for impeachment inquiries to begin. But this is happening in an environment where the intended consequence of impeachment, a subsequent conviction in the Senate, is, for all practical purposes, nonexistent.

The recent consternation over the prosecution of Trump, which I favor, is a direct result of this breakdown. If Trump had been removed and barred from office in 2021, which I believe he should have been, the consequences of a subsequent prosecution would not be anywhere near the same. It would not involve, as it does now, the prosecution of a potential political opponent of the current administration. Thus, one political dysfunction leads to another serious political problem.

Biden is clearly guilty, at minimum, of overlooking overtly sleazy behavior by his family in illicitly cashing in on his high offices. He may be guilty of more. It is a serious problem that this impeachment inquiry is occurring with relatively light evidence of any serious misdeeds. But what is perhaps more serious is the fact that, even if Biden is guilty of worse than we know now, there is little chance he’ll be removed from office.

This is the result of a quarter-century of political degradation. The impeachment and removal power of Congress is now neutered and amounts to little but political theater, meaning there is no clear way to hold a reprobate president accountable. And that is a much deeper problem.

Cliff Smith is a lawyer and a former congressional staffer. He lives in Washington, D.C., where he works on national security related issues.