Perspective: What is a mother?

Consider the case of Mina, a pseudonym for a real individual, who after fertility treatments finally became pregnant with twins through in vitro fertilization. After their birth, a court ordered the children be taken away and given to two separate families — not because Mina had done anything wrong, but because the IVF clinic had mistakenly implanted embryos from other couples into her womb.

The court declared Mina was not the mother of these children.

What is a mother? What does it mean to be a mother? How does that differ from being a father? Or does it not differ at all?

These are the deep questions raised by University of Colorado law professor Jennifer Hendricks in her newly published book, “Essentially a Mother: A Feminist Approach to the Law of Pregnancy and Motherhood.” Mina’s case appears on the very first page.

Hendricks observes that throughout history, identifying the mother of a child was a straightforward matter: a particular child was delivered of a particular woman. A mother was a woman who carried a child for nine months and gave birth to the child.

Identifying the father of a child was a trickier situation. Historically, Anglo-Saxon law deemed the husband of a woman to be the father of her children, no matter the circumstances. The man gained that right as the result of his prior commitment through marriage to the mother of the child.

With the arrival of DNA technology, paternity became both identifiable and claimable on the basis of genetics alone. A man could claim to be the father of a child, with the right of access to and decision-making power over the child, even if he had no ongoing relationship at all with the mother of his child. With the advent of this technology, our legal system faced a moment of decision it had never faced before: do genes establish parenthood?

According to Hendricks, it was both easy and unjust for modern courts to base parenthood on genes. It was easy because both a father and a mother pass on genes in equal measure: the courts could assert sex equality in reproduction by adopting a genetic standard. But this standard was also wrong, according to Hendricks, because genes are clearly not all there is to successful reproduction. Our understanding of the role of DNA has not changed the huge disparity in reproductive effort between men and women: women invest labor for nine months, with attendant possibilities for serious illness, serious injury and even death.

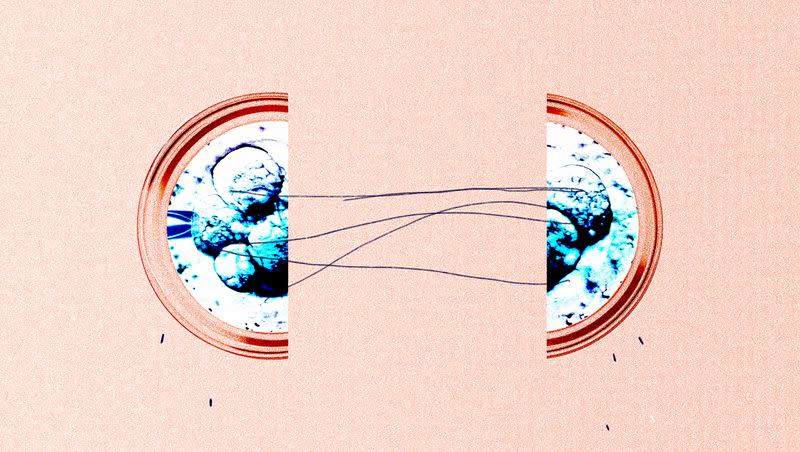

In addition, science has also demonstrated through recent discoveries that the woman’s body is no mere passive incubator of a child. Maternal-fetal microchimerism takes place, where cells from the mother’s body become part of the fetus, and cells from the fetus become part of the mother’s body. The uterine environment, we now know, plays an enormous role in shaping the epigenetics of the fetus, with results affecting the rest of their life.

Furthermore, the fetus is primed to be soothed in an emotional sense specifically by the smell and sound of the woman who carries it. Breastfeeding is also a reproductive effort not shared by men, and one which also shapes the newborn both physiologically and psychologically, with long-lasting effects on the child (and also the mother).

Related

These enormous differences between men and women in reproductive effort and the enormous differences in intensity and intimacy of the relationship established with the fetus are erased in a legal context where genes alone determine parenthood, and that can only lead to mischief, argues Hendricks. Whereas in the early part of the 20th century, courts looked to the caretaking relationship, the symbol of which was the mother-child bond forged in pregnancy, childbirth and lactation, to adjudicate parenthood, “the law switched to defining women’s parental rights in terms of men’s biology, with the contributions of genes trumping the relationship of pregnancy ... courts turned genetic fatherhood into a tool for genetic fathers to force connections with both children and their birth mothers.”

The most egregious example of the mischief that ensued was U.S. courts granting rapists parental rights with regard to the child. But Hendricks provides many other examples, such as the right of unwed fathers, even those who have never met the child they sired, to block a mother’s decision that adoption is best for the child. As Hendricks puts it, “defining parenthood in terms of genes denigrates gestation, which in turn denigrates women as a class and caretaking as an activity.” The emphasis on genes is “fake equality because it ignores an important biological difference for the sake of making sure men can automatically get what women have.”

This societal mischief was intensified by other technological advances that allowed the extraction of ova from women. Now the ovum of one woman could be placed in the uterus of another. In such a case, who is the mother of the resulting child? Once again, the law took the easy but also unjust path of concentrating solely on genes: Hendricks notes that “because gestation has no analog in biological fatherhood, (courts) disregarded nine months of caretaking to write gestation out of the parentage formula.”

It would be the ovum and who paid for procuring that ovum that determined who the mother of the child was, not who bore the child in her body. Indeed, in the case where an ovum was purchased by a male, the child would have no mother at all, according to our current legal framework: both the woman who produced the ovum and thereby donated genes to the child, as well as the woman who formed an intense and intimate biological relationship with the child through gestation, are completely erased.

Because the law elevates men’s mode of reproduction as the template for establishing parental rights, the outcome can only be described as misogynist. According to Hendricks, the law sees genes as a blood tie, “but for mothers, (connection) includes the actual shared blood of gestation as well as the metaphorical blood of a genetic tie.” Unless this is acknowledged, parenthood is being defined in solely male terms, which “treats gestation as a menial and meaningless contribution to the creation of a new life,” despite science telling us emphatically that it is neither.

Indeed, we even have examples of legal frameworks from other cultures in which the reproductive labor of women is taken extremely seriously in a way that ours does not. For example, in Muslim societies, if a mother breastfeeds another mother’s child, then her children and the other child she breastfed become something akin to siblings (“milk siblings”) as a result, and these children can never marry each other, just as genetic siblings cannot. Her reproductive labor forges a legally significant relationship where none previously existed — her labor is both meaningful and powerful.

While Hendricks is not arguing for milk siblingship, what she is doing is inviting us to rectify the injustices in our law that stem from not taking the reproductive labor of women into account at all, of stripping that labor of its meaning and power. To do so, we must “reason well from the body.” We must look — really look — at what male and female bodies are and are not doing, and write our laws accordingly.

For Hendricks, this means that “the person who gives birth to a child is that child’s initial family. She is therefore also the person who should make initial decisions about who else should join that family. ... Genes alone are not enough [to] claim connection with a child.”

Hendricks is forthright about what that rectification would look like in a legal sense. In the case of unwed mothers, that means the court’s deference to her decision whether or not to parent the child with the genetic father or to place the child for adoption. In the case of surrogacy, it means that surrogacy contracts should be made unenforceable, and that the relinquishment of a child in surrogacy must be placed under the same legal framework as adoption. This is precisely the current legal approach taken by the United Kingdom with regard to surrogacy.

Jennifer Hendricks has done us all a service by problematizing a legal framework that does not respect sexual difference between men and women. In doing so, she gives us the chance to restore both humanity and justice to our law.

Valerie M. Hudson is a university distinguished professor at the Bush School of Government and Public Service at Texas A&M University and a Deseret News contributor. Her views are her own.