Perspective: The pioneer legacy is an immigrant legacy

Seth Maxfield was a pioneer, settling in Utah in 1870. Like so many others, he made the trek west after arriving in the new country.

He was also my great-great-great-great-grandfather.

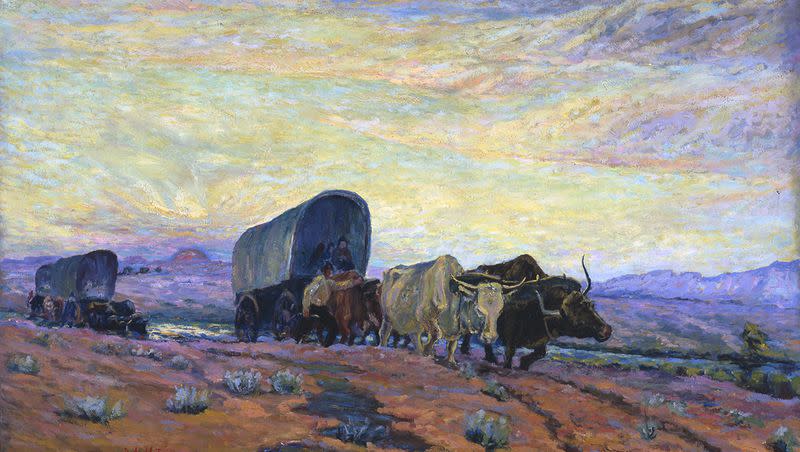

Much like I remember my ancestor, many Utahns will celebrate their pioneer heritage this July 24. On Pioneer Day, we remember the sacrifice and resilience of the state’s settlers. We honor their sacrifice, their devotion and their fortitude. Much like the Latter-day Saint pioneers found a place for their families to live safely and peaceably, we can celebrate this Pioneer Day by supporting immigration reforms so that other modern-day pioneers can find their own refuge.

The pioneer legacy is an immigrant legacy. After being forced out of Illinois and Missouri, 19th-century Latter-day Saints turned beyond the borders of the American frontier looking for peace. Thousands upon thousands of faith-driven individuals trekked along the barren plains of Iowa, Nebraska and Wyoming to reach the Salt Lake Valley. For many, this was not their first migration. By 1890, more than 70% of Utah’s occupants were born outside of North America, mostly in western Europe.

These two-time pioneers — champions of both the trail and the sail — were products of a systematized, efficient emigration system. As early as 1840, Latter-day Saint missionaries in England organized the passage of shiploads of converts from Liverpool to the United States, where they traveled by rail, steamboat or wagon to Nauvoo.

By the time Brigham Young led the Latter-day Saints westward to the Great Basin in 1847, this system had become superb. Entire ships were chartered; guidebooks and instructions were delivered; the Perpetual Emigrating Fund was formed to offer loans to migrants, according to financial need. It was, as one historian wrote, “the only successful, privately organized emigration system of the period”; wrote another, it was “the most successful example of regulated immigration in United States history.”

But despite its effectiveness — and, perhaps in part, because of its effectiveness — the Latter-day Saint immigration system faced the suspicion of United States officials. The state-sanctioned violence that plagued Latter-day Saints in Illinois and Missouri was past, but now the attack was at the highest level.

At his annual address to Congress in 1883, President Grover Cleveland proposed a blanket ban on Latter-day Saint immigration into the U.S., similar to the existing Chinese ban. Shiploads of Latter-day Saints were held at Castle Garden (the predecessor to Ellis Island) on dubious claims of “pauperism.” American diplomats traveled through western Europe and Scandinavia, begging those country’s civic leaders to keep Latter-day Saints from leaving for America.

The days of religious-based discrimination in our immigration policy is not that far behind us. But even if the motive is not religious, large groups of migrants face similar hardships today. In addition to the religious-based persecution that causes many refugees and asylum-seekers to migrate, many other immigrants face other challenges that cause them to abandon their homes in search of better opportunities — and refuge — in the U.S.

Related

The Dignity Act is a way to protect these migrants. The bill is supported by both Republicans and Democrats, and it addresses priorities for both camps. It offers funding for security at the southern border, and it creates a path to citizenship for many of the undocumented, law-abiding individuals already living within the U.S. It also would make significant changes to the asylum system, some aimed at efficiency, though the proposals raise concerns about asylum access.

Both of Utah’s senators — Mike Lee and Mitt Romney — descend from Latter-day Saint pioneers. Several of Lee’s ancestors became Latter-day Saints and walked across the plains. Romney’s ancestor, Miles Romney, joined the church in England and migrated to Nauvoo. His son, Miles Park Romney, was forced to flee to Mexico to practice his religion. Lee’s and Romney’s support of the Dignity Act, in many ways, will honor their family’s pioneer legacy.

This Pioneer Day, in addition to remembering the bravery and resilience of our pioneer ancestors, let’s remember the immigration system they built and the refuge they found — and let’s help others find a place, too.

Jennie Murray is president and CEO of the National Immigration Forum.