Perspective: How religious faith and a sense of agency corresponds with mental health

“Sisterhood is powerful.” That was an early slogan of feminism, but it’s hard to imagine it being used to describe young women today.

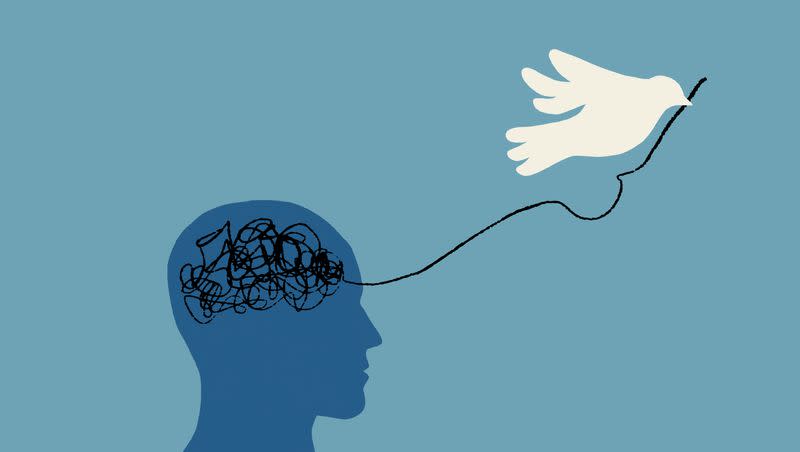

In fact, as a number of scholars have recently noticed, the mental health crisis being experienced by many teen and young adult women may have something to do with how little power they feel they have.

Writing for the Free Press recently, Jonathan Haidt cited a widely accepted theory in psychology about differences in how people perceive how much control they have:

“Some people have an internal locus of control — they feel as if they have the power to choose a course of action and make it happen, while other people have an external locus of control — they have little sense of agency and they believe that strong forces or agents outside of themselves will determine what happens to them.”

And, he noted, “Sixty years of research show that people with an internal locus of control are happier and achieve more. People with an external locus of control are more passive and more likely to become depressed.”

A number of factors have led young women — and liberal young women in particular — to have more of an external locus of control than previous generations or than their conservative peers. Social media certainly seems to have had an outsized effect on girls.

But it is also the messages that young progressives have embraced as a result of their political ideology — especially the idea that the world is made up of oppressors and victims (or good people and bad people) and the idea that another person’s words can cause a person deep and lasting harm.

What’s interesting is that these are ideas that liberals often associate with being a conservative or being strongly religious. It is not uncommon to see the secular media portray religious young people as powerless, simply following orders from their elders or from God.

Related

Perspective: How religion helped teens during the pandemic — and one way it didn’t

Finding the light: The science behind spirituality as an antidepressant

And it is also not uncommon to see religious folks portrayed as believing that the world is made up of good people and bad people, or as being so sensitive as to think that a few words can cause them real harm. They are the ones who want to “ban” books and who condemn swearing or taking the Lord’s name in vain.

But multiple studies have found religious belief is correlated with positive mental health. An interesting paper on Orthodox Jews published in the Journal for the Scientific Study of Religion found that during the pandemic, “A Closeness-to-God Index predicted lower levels of depression and anxiety, less perceived stress, and less loneliness.”

“Congregational prayer also predicted lower stress and less loneliness, but the magnitude of the effect was smaller.” The authors concluded: “The findings provide empirical support for … the positive effects of religion on mental health.”

In other words, good mental health was not simply because these community members had friends or did things together. It was something about the way they felt in relation to God and the world around them that led to better mental health outcomes.

So what is the difference between this conservative religious worldview and the progressive secular one?

For one thing, rather than making kids feel like cogs in a machine, religion teaches them that God sees them as individuals who are valuable and helpful. Secular progressives see structural barriers to change and increasingly believe that these are all but impossible to change without massive government interventions.

My fifth grader this year was shown a video in school that said the world would end in 2030. It’s hardly the kind of thing that makes one feel empowered; rather, it just makes you feel like you’re doomed and there’s nothing you can do (though one girl did announce she was going vegan as a result). Religious folks are still of the opinion that small actions by individuals have the potential to fix things.

This idea of human dignity — so central to Judeo-Christian teachings — is a vital part of helping people feel like they have agency in a world that otherwise can feel overwhelming. While secular liberals may divide the world into good people and bad people, or oppressors and victims, religious people tend to believe that everyone is capable of good and evil. But this too gives them a sense of power — power that they can change themselves and that they can influence the behavior of others.

The current attitudes among young progressives were not always the attitudes on the left. Individual empowerment (which often led to communal empowerment) was commonly preached in the past. Indeed, it was preached by folks on the left who were often religious themselves.

While Haidt suggests that one answer is restricting the use of social media or getting colleges to stop teaching all this victimhood claptrap, it’s also worth thinking about how religious affiliation helps young people find meaning and take control of their lives. We may not be able to talk everyone back into a faith-based community, but perhaps the constant derision of them might not be warranted.

Naomi Schaefer Riley is a senior fellow at the American Enterprise Institute, a Deseret News contributor and the author of “No Way to Treat a Child: How the Foster Care System, Family Courts, and Racial Activists Are Wrecking Young Lives,” among other books.