Perspective: ‘Without this bill, I will die’

Imagine the fortitude it takes to sit in front of a legislative committee to testify that without passage of the bill being discussed, you will die. And then to hear comment after comment about why this bill needs to die, with barely a word acknowledging your presence.

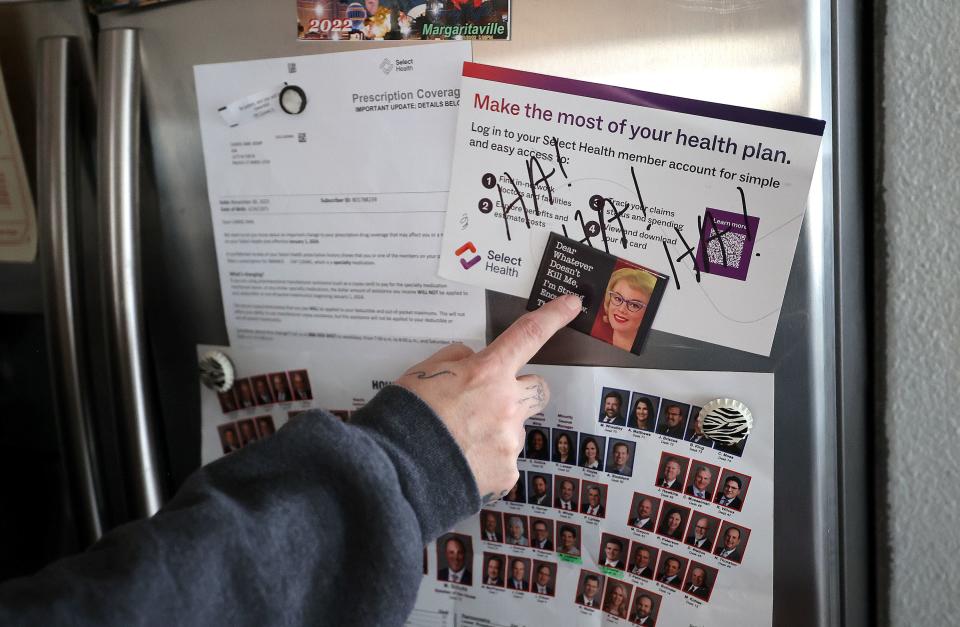

Carrie Ann Kemp, also known as the “Maturation Lady,” sat through that very uncomfortable experience last Thursday, when SB152 was up for discussion. As opponents discussed this bill, she was left feeling like she had no value as a human being.

The bill in question is one that deals with copay accumulators, or programs whereby insurance companies take money meant to help patients meet their annual out-of-pocket maximum and instead pocket the money.

For Kemp, her journey began in 2011, when she was diagnosed with breast cancer, a diagnosis that meant eight months of chemotherapy, a bilateral radical mastectomy, a complete hysterectomy and 18 reconstructive surgeries. She then had 10 cancer-free years, a milestone that usually means the cancer is not coming back.

In April 2022, five months after celebrating a decade of being cancer-free, she was stunned to learn cancer had returned, and this time there is no cure. However, there is hope in a drug treatment that keeps her cancer from progressing. That medication is Ibrance, a drug that costs $24,000 per month.

On Kemp’s current health insurance, her out-of-pocket maximum for a year is $12,000. For the last two years, Pfizer, the company that makes Ibrance, sent the pharmacy that dispenses the medication a $12,000 payment, meant to benefit Kemp. This year, however, her insurance company did not apply that $12,000 to her out-of-pocket max, but instead kept it and told her she still has the full $12,000 to go.

She cannot pay it.

When asked what it means to have no medication for February, let alone the foreseeable future, she said, “It means I’m actively dying.”

Who is affected?

Cancer patients like Kemp are not the only ones impacted by insurance companies refusing to put pharmaceutical company dollars toward the patient’s account. Patients with diseases like ALS, or “Lou Gehrig’s” disease, multiple sclerosis, hemophilia and cystic fibrosis, Crohn’s, HIV/AIDS and others are also harmed under these practices.

These copay accumulator adjustment policies (CAAPs) disproportionately impact patients suffering from serious illness and are particularly harmful to patients who are low-income or who are persons of color, according to the national group “All Copays Count Coalition.” Of the people who depend on copay assistance programs nationwide, 69% make less than $40,000 a year.

CAAPs end up interrupting necessary treatment, driving down the effectiveness of the treatment and leading to an increase in other costly health issues. Or, in Kemp’s case, death. The practice is so egregious that the Federal Employees Health Benefit Plan announced earlier this year that it would not accept any plan that employs it.

Utah is not alone

Bills banning the practice of not applying money to a patient’s copay have been introduced in the Utah Legislature for the last three years. In 2022, it was Sen. Evan Vickers, R-Cedar City, running the bill. For the last two years, Sen. Curt Bramble, R-Provo, has been the originating sponsor.

Opponents of the bill include insurance companies and businesses who claim that eliminating copay accumulators would significantly increase health care costs for all.

There are currently 19 states, plus Washington, D.C., and Puerto Rico, that ban the practice of copay accumulators, including three of Utah’s neighbors: Arizona, New Mexico and Colorado. Other states include Texas, Georgia, Oklahoma, Arkansas, Kentucky, Tennessee and Virginia. Data from these states indicate that there is no difference to consumers in the price of health insurance, whether a state has banned copay accumulators or not.

Last fall, a federal district court struck down a federal rule that allowed health insurers to not count drug manufacturer copay assistance towards a beneficiary’s out-of-pocket costs, calling the rule “arbitrary” and “capricious”. The U.S. Department of Health and Human Services appealed the court ruling in late November, and less than two months later, dropped its appeal.

The rule that the court struck down only applies to insurance companies governed by state governments, hence the need for Utah’s bill. And, as some argue, a federal solution.

For Carrie Ann, she knows this is her one shot.

“Next year”, she said, lawmakers “can come visit me at Eastlawn (Memorial Cemetery) and tell me how it’s going.”

Holly Richardson is the editor of Utah Policy