Peru’s Economic Miracle Destroyed by Non-Stop Political Chaos

- Oops!Something went wrong.Please try again later.

- Oops!Something went wrong.Please try again later.

(Bloomberg) -- A year ago today, Peru fended off the biggest challenge to its democracy in years. The ensuing months have only proved that the country is still deeply broken.

Most Read from Bloomberg

Carlyle’s Rubenstein Is in Talks to Acquire Baltimore Orioles

Americans Rush to Portugal Ahead of Changes to Expat Tax Breaks

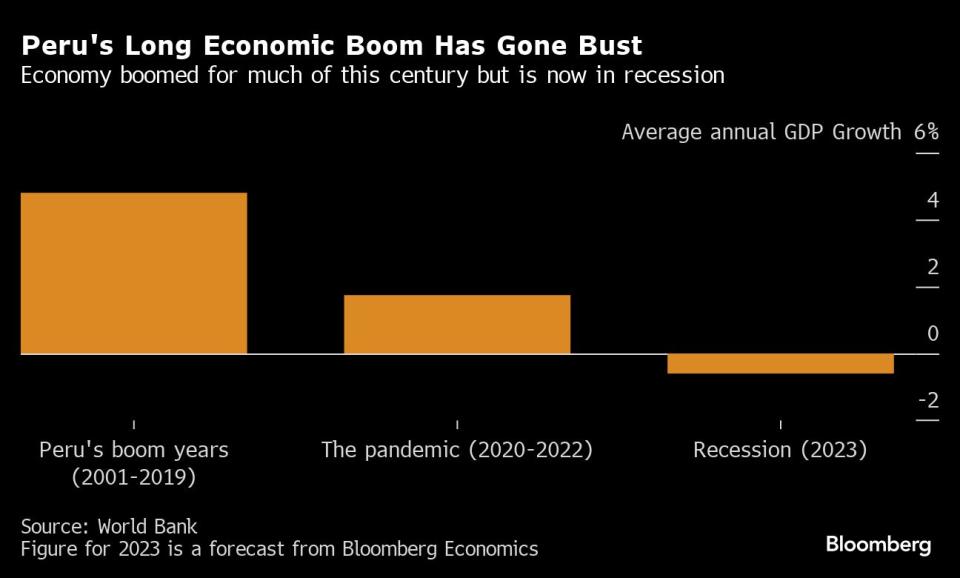

The attempted coup by then-President Pedro Castillo came at a time when the South American nation was already vulnerable from years of political chaos that had begun to overshadow its potential as a mining and agriculture powerhouse. Now under President Dina Boluarte, it is mired in the harshest recession in two decades excluding the pandemic. Its branches of government are all in crisis and experts are sounding alarm bells not just about its economy, but about the health of its democratic institutions.

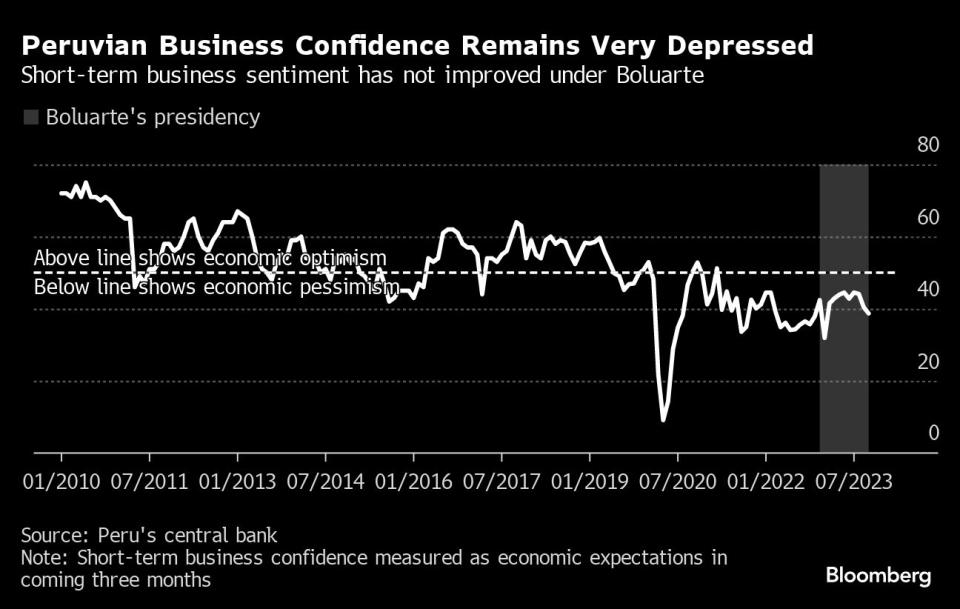

The nation is grasping for ways to make its government more stable after cycling through seven presidents in eight years. But it has not found a fix — and investors know this. Business confidence is close to historic lows and rebooting a once fast-growing economy will be challenging. For a country that averaged 4.8% growth for almost 20 straight years this century, its economy is now expected to contract 0.6% in 2023.

Read the story in Spanish here.

“The hidden costs of political instability are sometimes underestimated, but in practice they are very important,” Alex Contreras, Peru’s finance minister, told Bloomberg in an interview last week. “I think what we need is to restore a balance between the different branches of government,” he added, referring to Peru’s unique political system, where congress can easily fire the president.

It all serves as a cautionary tale in a world where politics has become more and more polarizing. Peru’s experience shows there is a real cost to political volatility, including for its more vulnerable. Poverty levels in Peru are at 27.5% of the population, as high as they were in 2011, undoing over a decade of growth that was supposed to lift people from poverty. What’s more, the government acknowledges it will rise again this year. Unemployment, too, is rising due to the recession.

Boluarte and congress are facing single-digit approval ratings. Prosecutors allege their own attorney general conspired with lawmakers to trade votes for impunity. Peru’s top judges are defying the country’s commitments to international organizations. Dozens were killed in anti-government protests under Boluarte, but nobody has been charged for their deaths.

“Our democracy is now like a walking corpse, but it has no blood or pulse,” said Denisse Rodriguez-Olivari, a Peruvian political scientist at the European University Institute in Italy. “It looks like we are living in a democracy, it looks like everything is fine, but it is not fine.”

The country’s economy was only able to outrun its political problems for so long because of the steadiness of its central bank and finance ministry. It has a manageable deficit, low debt and no immediate liquidity needs. What drags the country down is by and large its endless political crises.

Read more: Impeachment Mania Unravels an Economic Miracle in Latin America

A central bank survey shows just how much that sentiment has become entrenched. In October, it asked business owners what factors were most limiting growth. The top two answers — political instability and social unrest — simply did not exist the last time the bank published the same survey in 2015.

Capital Flight

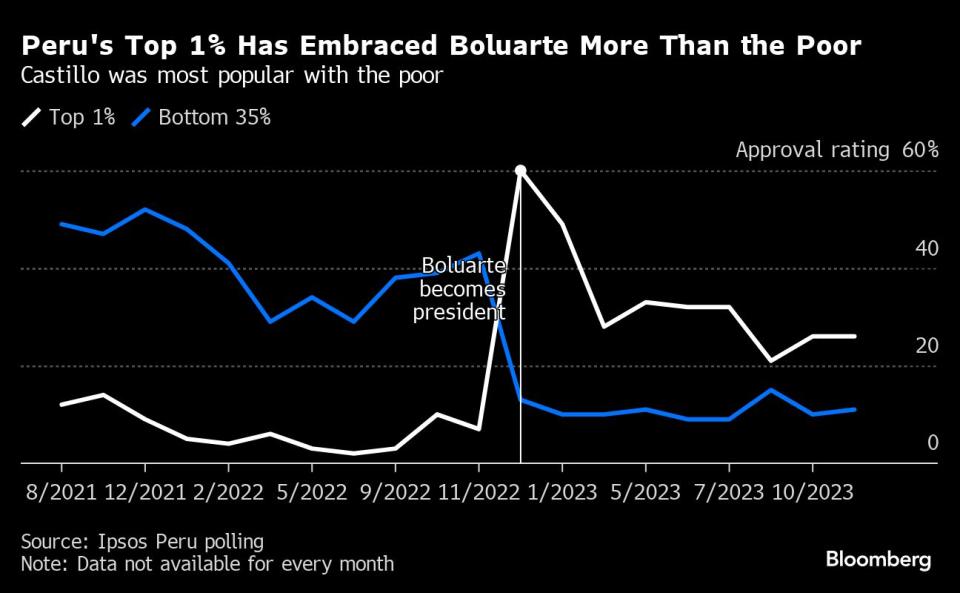

Peru’s business class has embraced Boluarte, who was initially elected as vice president in 2021 under Castillo. According to one poll, just 1% of Peruvian CEOs approved of Castillo’s leadership yet 79% approved of Boluarte.

Those results are mimicked in national polls, where Boluarte’s approval ratings with the rich are more than double those with the poor. Castillo’s erratic campaign for the presidency focused on uplifting the poor. While he did not help their cause, Boluarte has positioned herself closer to the tiny business elite.

The deaths at the beginning of her presidency still weigh over her popularity and post-presidential prospects. Peru is notorious for imprisoning more former presidents than any country in the world — Castillo himself is in prison over his failed power grab — and Boluarte has recently been hit with a constitutional complaint alleging she’s responsible for “homicide” over the lost lives.

Read more: Peru Frees Ex-Leader Fujimori, Defying International Court

Castillo was popular exactly where Boluarte is not. The almost 50 citizens who died in protests under Boluarte overwhelmingly came from rural and poor backgrounds likely to have supported Castillo, significantly alienating that sector of the population. Peru’s poorest region, Puno, sustained most of the deaths, and Boluarte has not visited the region once during her presidency.

Still, by the time Boluarte took office in 2022, some of the economic damage was already in motion.

Castillo’s Marxist-Leninist party was so scary to the country’s elites that it triggered the biggest capital flight in Peru’s history — $17 billion — in 2021. Similar bouts of capital flight have since taken place in Chile and Colombia.

Read more: Socialist Wave Sends Money Flying Out of Latin America

And by the end of Castillo’s presidency private investment had begun to fall and business confidence was as low as it is now. His government was so chaotic that at one point he was appointing a new minister every six days. While fears of a radical-left turn and a rewrite of the constitution turned out to be overblown, as they were never implemented, it merely compounded concerns among investors already on edge in the wake of the pandemic.

That confidence in the economy never recovered. Capital flight restarted again, with $1.9 billion leaving the country in the third quarter of this year, according central bank data. That’s the highest amount in over a year.

Saving Face

In public, business leaders have tried to be bullish about Peru’s economy.

Last month, the country’s largest industry groups hosted a conference focused on promoting confidence in the economy and a pledge to return to economic growth.

At the conference, Boluarte’s top deputy Alberto Otarola blamed the economic struggles on Castillo, and promised a swift turnaround under a business-friendly administration.

“We have three years to jointly govern,” he told the audience, referring to the time left in Boluarte’s term.

Business leaders certainly consider Boluarte an upgrade from Castillo.

“I am an optimist, I think the storm already passed and it was a very big storm,” Luis Enrique Romero, the chairman of Credicorp Ltd., told Bloomberg. Credicorp, owner of Peru’s largest bank, has warned it is bracing for increased loan delinquency due to the weak economy and looming rains triggered by El Nino. But once that is over, Romero says the country should return to growth.

“The dark clouds ahead are related to El Nino,” Romero said.

Contreras, the finance minister, pointed to what he sees as some silver linings. For example, congress has preliminarily approved adding a senate chamber and allowing for lawmakers to be reelected, which could limit political volatility if confirmed. Another positive note is tacit, he said, because Boluarte is not going to push for redrafting the constitution, a key concern under Castillo that was never put in motion.

Low Confidence

For all the public optimism, economic indicators and private remarks point to a different outlook.

Peru’s economy has contracted for five months in a row, private investment has plunged for four consecutive quarters, and employment has begun to fall. What’s more, tax revenue is coming in significantly below expectations, widening the fiscal deficit.

Peru’s credit rating with Fitch Ratings and S&P Global Ratings remains two notches above junk, but its outlook has been negative for over a year. With Moody’s Investor Service, it is three levels above junk, and its outlook has been negative for close to a year.

“With the rating agencies, yes, governance indicators have played against us,” Contreras said.

Business confidence, as measured by the central bank, is facing its longest negative streak in over a decade.

The country’s stocks and bonds are lagging the broader market rally this year. The benchmark stock index is up just 5.4%, compared to an average 15% gain across Latin America. And the 6.4% return generated by its dollar-denominated bonds trails the 10.7% average return on Latin American government debt, according to a Bloomberg index.

The finance ministry is betting the economy can grow next year by 3%, a virtually-unattainable goal even if it is to benefit from a low base of comparison this year.

But there’s a bigger problem in sight: Economists don’t think Peru can grow at a fast rate anymore. A fiscal watchdog estimates its GDP potential at 2.6% a year, and Contreras estimates 3%. Neither is enough to restore Peru’s pre-eminence among Latin America’s major economies or bring much change to its current state.

“What we are trying to do is to revert this low potential growth,” Contreras said.

--With assistance from Nicolle Yapur.

Most Read from Bloomberg Businessweek

Salesforce Signals the Golden Age of Cushy Tech Jobs Is Over

How the Biggest Boutique Fitness Company Turned Suburban Moms Into Bankrupt Franchisees

Hottest Job in US Pays $80,000 a Year, No College Degree Needed

At World Central Kitchen, José Andrés Is in the Middle of a Mess

SpaceX’s Colossal Starship Sets Pace in Race to Build Larger Rockets

©2023 Bloomberg L.P.