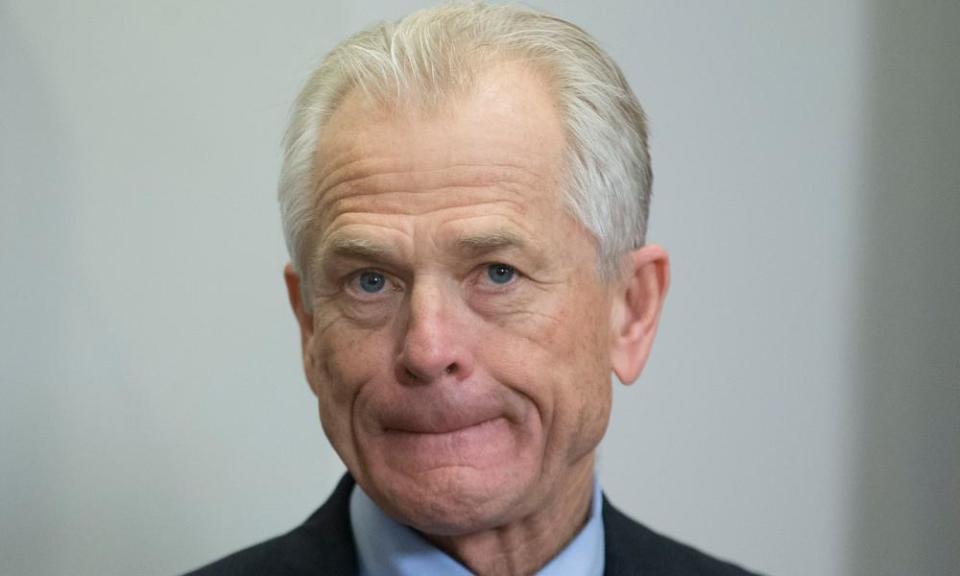

Peter Navarro; the economist shaping Trump's economic thinking

The White House’s metals tariffs plan has numerous casualties, the big winner is the man in charge of trade and manufacturing

Donald Trump’s threatened trade tariffs have claimed many victims: international trade, domestic steel consumers and Trump’s dissenting economic adviser Gary Cohn. But so far there has been one big winner – Peter Navarro, director of the Office of Trade and Manufacturing Policy.

Navarro was a key architect of Trump’s “America First” policy of economic nationalism and a tireless critic of China’s economic policies – one of his books is decorated with a map of America being stabbed in the heart with a knife marked Made in China.

Although he has agitated for aggressively protectionist trade policy since joining the Trump campaign in 2016, the tariffs are his first key victory.

During the campaign, Navarro, the only economics PhD in the Trump team, described his role as merely a facilitator. “The president – he’s the man who leads,” he told the Wall Street Journal. “He says, ‘I want to do this. How do we do it?’ The way I help is figuring out how you might do it.”

On his first full day in office, Trump announced he would pull the US out of the Trans-Pacific Partnership (TPP) but, hemmed in by free-traders, subsequently he has so far taken few steps to enact Navarro’s anti-China agenda.

But the resignation of the National Economic Council director Cohn earlier this week was a clear signal that the globalists in the White House are in retreat. Navarro, 68, is one of several names being floated to fill Cohn’s position.

That appointment might be no more than symbolic; Navarro’s hand is strengthening, and the metals tariffs Trump announced last week may be no more than an hors d’oeuvre to a larger economic agenda – one that strikes fear into free-traders.

Trump’s former campaign director Steve Bannon was Navarro’s early champion, announcing at the March 2017 Conservative Political Action Conference that the University of California, Irvine economics professor would be part of a team “rethinking how we are going to reconstruct our trade arrangements around the world”.

Navarro has long argued that trade imbalances and intellectual property theft by China are the true threat to US economic power. His thinking on China was laid out in two books: Death by China and Crouching Tiger: What China’s Militarism Means for the World.

In the first, he described China as “turning into the planet’s most efficient assassin”, and urged regulators to block Chinese acquisition of US companies. He also advocated that the US form partnerships with Europe, Japan “and other victims of China’s mercantilism” to resist China and bring actions against it through the World Trade Organisation.

In the second, he laid out a fearful scenario of Chinese “carrier killer” ballistic missiles and advocated maintaining military strength and regional alliances to defend America against the Chinese threat.

Despite being thwarted by Cohn and other more traditional thinkers in the White House during the first year of the Trump administration, aspects of Navarro’s philosophy still surfaced. It was Navarro who pushed Trump to threaten to pull out of Nafta and to use tariffs to force a renegotiation with Canada and Mexico; and it was Navarro who shaped Trump’s warning on German trade surpluses.

In a Wall Street Journal op-ed in March 2017, Navarro argued that “running large and persistent trade deficits also facilitates a pattern of wealth transfers offshore”. He warned “that foreigners will eventually own so much of the US that Americans will wind up working longer hours just to eat and to service the debt.”

That, it seems, was music to Trump’s ears. Navarro argued that “reducing a trade deficit through tough, smart negotiations is a way to increase net exports – and boost the rate of economic growth.”

Suppose, he proposed, “America successfully negotiates a bilateral trade deal this year with Mexico in which Mexico agrees to buy more products from the US that it now purchases from the rest of the world. This would show up in government data as an increase in US exports, a lower trade deficit, and an increase in the growth of America’s GDP.”

But while Cohn led the White House economics team, Navarro’s brand of economic nationalism was forced to take a back seat. Navarro was originally appointed head of a newly created National Trade Council; then head of the Office of Trade and Manufacturing Policy, reporting to Cohn.

Now with Cohn gone – a move the JP Morgan chief Jamie Dimon described on Thursday as “unfortunate” and “terrible” – Navarro may be unleashed.

On Wednesday, Navarro announced that under the administration’s tariffs plan Canada and Mexico would remain free of the new tariffs if they successfully concluded negotiations rewriting Nafta.

“There’s going to be an opportunity for Canada and Mexico to successfully negotiate a fair new Nafta, but if that is unsuccessful then tariffs will be imposed,” he said.

But will Navarro make it to become White House chief economics adviser? He told Bloomberg TV he’d be “honored” but added he was “not on that list, let me be clear”.