The petrifying return of nuclear anxiety

The world might end with a mistake.

New computers or sensor equipment could generate unreliable data, for example. Perhaps a military exercise, intended to simulate the outbreak of war, could be perceived as the real thing. A breakdown in communications might leave officers in the field uncertain of their orders. Or a rogue general or political faction could hijack crucial units or weapons without the approval of their governments.

For a generation of writers, filmmakers, and other artists, scenarios of unintended Armageddon were raw material. After the Cuban Missile Crisis in 1962, publishers and studios created a whole genre of popular culture about the outbreak of nuclear war. Unlike postapocalyptic fictions that imagine life after a more or less devastating exchange (a scenario that continues to thrive in video games), films like Fail Safe (1964), The Bedford Incident (1965), and, of course, Dr. Strangelove (1964) focused on the events leading up to the fatal launch. In what sequence of events, they asked, could it seem reasonable and even necessary for decent men (and they were mostly men) to do the unthinkable?

Despite a revival in the Reagan Era, the genre waned in the 1990s. In the military thrillers of the period, terrorists tended to replace Soviets as the atomic enemy. The moral problematic correspondingly shifts from the paradox of mutually assured destruction to an encounter with suicidal insanity. The plot of By Dawn's Early Light (1990), among the last big productions to imagine nuclear war between the United States and USSR, prefigures the shift. In its version, the apocalypse is unleashed by Communist hardliners who contrive to launch a NATO missile based in Turkey at the USSR. Ominously, their target is the city of Donetsk, in the Donbass region of Ukraine that Russia still places within its sphere of influence.

Not all these works amounted to great, or even good, art. While authors and producers sometimes boasted of their technical accuracy, their main goal was to sell books, tickets, and advertising slots. Still, commercial motives can serve civic and even moral purposes. Precisely because they gave audiences the scare they were looking for, they underlined an essential fact about nuclear war: Once the process of escalation gets underway, it could be extremely difficult to interrupt.

Especially for younger Americans who don't remember the Cold War, the stagnation of the Russian invasion of Ukraine is an occasion to learn that lesson all over again. The New York Times reported on Tuesday that experts are increasingly concerned that the prospect of strategic defeat might lead Vladimir Putin to order the use of a nuclear weapon. A number of dominos would have to fall before that course would be considered, they caution; still, the chances of confrontation between the world's largest nuclear powers are higher than at any time in more than thirty years.

Military planners and scholars never ceased to consider these risks, of course. The Times report emphasizes the dangers of new weapons, which have reduced destructive potential that might make them more tempting to use. But tactical or non-strategic arms have been part of the nuclear arsenal for decades. In fact, they're central to the plot of The Bedford Incident, which was conceived as a serious alternative to the satirical Doctor Strangelove but ends the same way —with the outbreak of World War III.

The truth is, no one knows how the United States would answer the Russian use of nuclear weapons, tactical or otherwise. As my colleague, Jason Fields, notes, one of the terrors of nuclear escalation is that the specifics of any response must remain secret until actually executed. There are also political complications. Although the U.S retains unilateral control of our nuclear weapons, including those based in Europe, significant changes in their deployment, let alone use, would require coordination with other NATO members. The issue is apparently on the agenda for Thursday's emergency meeting in Brussels, although it's worth balancing any information that transpires against the adage that "those who know don't say, those who say don't know."

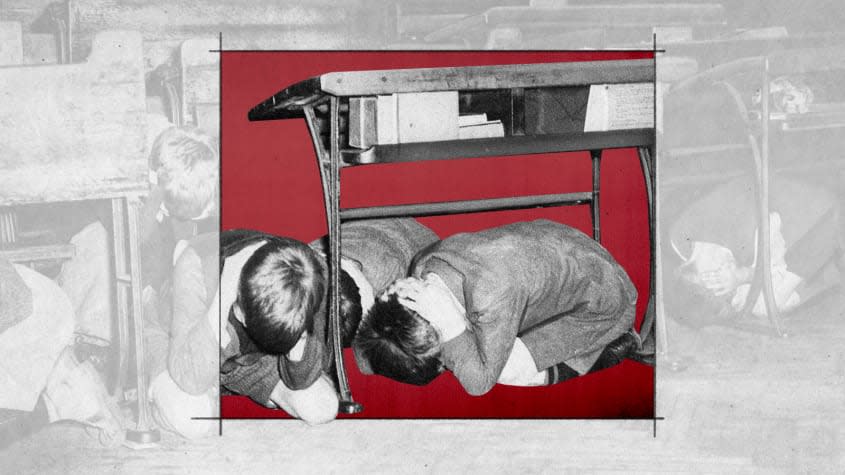

Widespread opposition to a no-fly zone is an encouraging sign that we haven't entirely forgotten the lessons of the Cold War. If we make it out alive, this crisis might even stimulate a revival of the kind of geopolitical popular culture that may have played a small role in preventing the nightmare of nuclear war by depicting it so personally and vividly — an intentional contrast to the visual abstraction and clinical vocabulary that dominate fictional war rooms.

In the meantime, though, there are worse ways to spend an evening awaiting news from Ukraine than revisiting the old Cold War classics. Still not scared? Spend a few minutes on the Nukemap website and reacquaint yourself with the sum of all fears.

You may also like

Putin quotes Jesus to justify invasion of Ukraine

Gen. David Petraeus explains how Ukraine keeps picking off Russian generals

Putin's invasion is hastening Russia's decline. Let's heed the warning.