PFAS contamination in south Tucson challenges historic cleanup, revives health concerns

TUCSON — Linda Shosie drove down the streets of southside Tucson pointing out, across several blocks, what she’s determined are “clusters” of disease.

Knocking door-to-door, through home visits and phone calls, she collected testimonies of people who, like her family, suffer from cancer or other severe illness, presumably linked to drinking water contaminated decades ago.

Shosie grew up near the Tucson International Airport, where companies leasing the land for industrial and military defense-related activities produced hazardous waste that seeped into aquifers from the 1940s to mid-1970s. Community pressure and the early death toll linked to water contamination prompted the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency to declare the area a Superfund site in 1983, a national priority area for long-term cleanup.

But remediation is not over, and the government keeps identifying new unregulated contaminants to add to the list.

Over two decades ago, water testing revealed the presence of 1,4-dioxane in wells near the Superfund site, and an additional treatment facility was built 12 years later.

Then “forever chemicals,” or PFAS, were found. Tucson Water tested and shut down wells, blended water and invested in treatment, even though there is still no federal regulation for the contaminant. Residents of southside Tucson don’t receive water from these or any other contaminated wells, but past exposure and its effects continue to worry residents. Many contend broader health screenings and compensation are still due.

For nearly three decades, southside residents were unaware they were drinking and bathing in water contaminated with trichloroethylene, a volatile organic compound that is linked to several types of cancer and that can have harmful effects on the immune and nervous system and can lead to birth defects.

Hughes Aircraft Co. and McDonnell-Douglas Corp routinely dispose of degreasing products, solvents and other chemicals used in aircraft manufacturing, maintenance and training that contaminated water and soil. The finger-shaped TCE contamination plumes stretched about 1.5 miles wide and 5 miles long.

The EPA declared the companies, acquired in 1997 by Raytheon and Boeing respectively, responsible for the environmental contamination. The U.S. Air Force, the city, and the Tucson Airport Authority were also added to that list and forced to establish a trust fund to pay for the remediation. In 1994, Tucson Water began operating the Tucson Airport Remediation Project or TARP, initially built to treat TCE exclusively.

Dioxane and PFAS, short for perfluoroalkyl and polyfluoroalkyl substances, were likely also used at the air bases, but agencies and the utility didn’t test for them until years later.

There is still no maximum contaminant limit for dioxane nor any PFAS chemicals.

Treatment for dioxane, classified by the EPA as a “likely human carcinogen,” started in 2014. An EPA spokesperson said the agency expects to officially add the chemical to the Tucson Superfund site’s list of contaminants of concern in February. There is still no discussion about adding PFAS to that list.

In December, the federal regulator requested all responsible parties to perform a remedial investigation and site investigation for PFAS. The Air Force, the Air National Guard and the city agreed to start sampling. The Tucson Airport Authority will start a site assessment in March, which will eventually lead to sampling.

After parties complete the remedial investigation, the EPA will evaluate remedial alternatives for cleanup, officials said. There is no definite timeline for PFAS remediation.

Fears of PFAS: Arizona prepares to test hundreds of drinking water systems for toxic 'forever chemicals'

Mapping community illness

Shosie attributes a string of family health issues to the polluted water, including the death of her 19-year-old daughter to lupus more than a decade ago. Six of her eight children suffer atypical health complications. Her oldest child was born prematurely in 1975 with several ear, nose and throat problems. Her second child was born prematurely with a nasal deformity. Her third child was born with a cleft palate and bone age delay.

A doctor’s note from Southwest Pediatrics El Rio, viewed by The Arizona Republic, said her granddaughter’s illness “may be associated with some chemicals she has been exposed to in her environment.”

In 1984, the Agency for Toxic Substances and Disease Registry surveyed residents near the Superfund site and found significantly high ratios of skin problems, anxiety or nervousness and cancer. But the agency could not conclude that these higher rates of disease could be attributed to “any specific exposure.” Follow-up studies were required.

To this day, no one has completed a long-term study that would give Tucson’s southside residents a holistic picture of how all of the pollutants have affected their health.

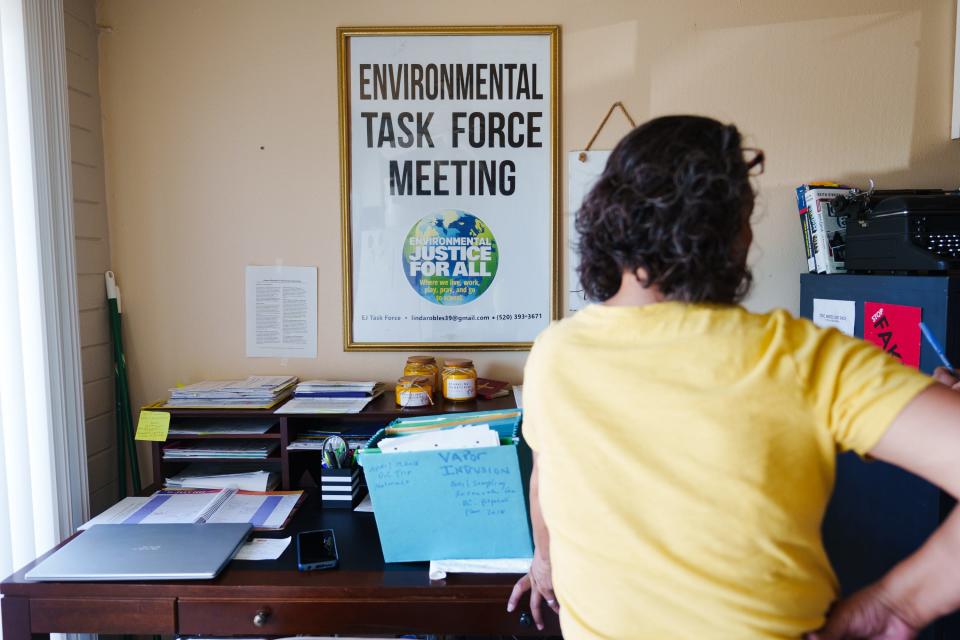

Mapping the dimension of the tragedy was Shosie’s way of coping. In 2014, she started her own survey. It seemed that at every second house, someone was suffering from a severe disease.

“You can imagine I'm crying with every mom that I've interviewed because many mothers like myself witnessed the death of their child,” she said.

Asking simple questions like name, address or ZIP code, phone number and health issues, Shosie collected about 470 responses, many of them on paper, stored away in a filing cabinet. Her survey, and personal experience, shows a trend that warrants further investigation, she said.

Shosie spearheaded the filing of new claims against the U.S. Air Force, rallying residents, and has sought attorneys to start a new lawsuit. None has come to fruition yet.

More environmental news: Arizona says developers lack groundwater for big growth dreams in the desert west of Phoenix

In 1985, the law firm of Baron and Budd filed a mass tort lawsuit, involving 1,618 residents of southside Tucson, against the city, Hughes Aircraft, and Tucson Airport Authority. The last settlement was reached in 2006. Behind it was a decades-long process of community action.

At the time, it was one of the biggest groundwater lawsuits in the country.

The scenario could hardly repeat itself today, according to Rick Gonzales, a southside Tucson resident and law firm associate in the claim.

“Back then, we had the horse in front of the cart,” Gonzales said. They had an extensive amount of evidence, national attention, and a scientific and medical team working by their side. They were also arguing for damages from TCE contamination.

Affected residents would need to prove that other contaminants caused their illness above and beyond any effect from TCE. They would also need to prove that exposure came from the airport area, which was a challenge, considering there are traces of PFAS in many products and of dioxane.

Southside residents have not been drinking water from those wells since 1981.

Early lawsuit agreements guaranteed that residents near the Tucson International Airport would receive water from Avra Valley well fields. After the TARP treatment plant started operating in 1994, the utility sent that water to about 60,000 residents living north of Irvington Road. That came with its own challenges.

In 2016, with the change in EPA health advisories, Tucson Water expanded PFAS testing and found high concentrations of the chemical in the Superfund area.

TARP had no system in place to treat PFAS, but the carbon filters used in the process to treat dioxane were retaining it.

“This was the serendipity,” said Tucson Water Director Jon Kmiec. The utility had installed the granular activated carbon filters as part of the process to “quench” hydrogen peroxide used to remove dioxane from water.

“What we found out is it was actually taking out PFAS, that we had no idea was in the water,” Kmiec said.

The utility started monitoring the contaminant and changed the GAC filters every six months to remove PFAS, an unforeseen $600,000 increase in operating costs.

“This was never a PFAS treatment plant,” Kmiec said. “We've just been living and making sure that we can treat PFAS while we are serving the community.”

2 contamination plumes to treat

Under Superfund agreements, the TARP plant is required to treat TCE and dioxane only. But the presence of PFAS, and its threat over public health, has complicated and even disrupted operations.

For about five months, from mid to late 2021, the city and the utility temporarily closed the plant. Water testing indicated that PFAS levels in wells south of the TARP plant had jumped dramatically. GAC filters that were already sequestering PFAS would not handle the increase. This new level of contamination could “overwhelm the facility,” officials said. After establishing new measures to lower PFAS levels and getting EPA approval, TARP now sends water, cleared for PFAS and all other contaminants, into the Santa Cruz River wash.

Agencies and responsible parties have studied, delimited and reduced both the TCE and dioxane plumes. Kmiec said the utility still does not know the size of the contamination plume of PFAS coming out of the Tucson International Airport area. The utility has spent over $30 million out of pocket to deal with PFAS contamination across its distribution area. It could take tens if not hundreds of thousands of dollars more to solve the issue.

The growing challenge to deal with PFAS also threatened to interrupt unfinished work: cleaning up the water from TCE.

The Arizona Department of Environmental Quality and then-Gov. Doug Ducey announced the allocation of $25 million in federal funding in December to build a PFAS treatment facility next to TARP and allow remediation to continue. Tucson Water estimates it will take at least three years to design it.

More Arizona news: Arizona State of the State: Water supply, education major priorities, new governor says

"When 1,4 dioxane was first discovered, it probably took 10 years before (the federal government) actually started doing anything about it," said Yolanda Herrera, a southside resident and longtime community advocate for safe drinking water.

She believes it’s about time for PFAS regulations and treatment.

For over 28 years, Herrera has been a volunteer on the Unified Community Advisory Board, a board of residents and agencies that meets quarterly to track the Superfund cleanup progress, and has served over 10 years as the community co-chair. She continues to advocate for safe drinking water just as her father did in the late 1980s. She believes there is a need for new community members, especially younger generations, to sit at the table and hold the responsible parties accountable.

“The only people that don't retire are volunteers," Herrera said. "Our job is to keep asking the questions: 'What else are they finding?'"

Turnover in agencies and the changes in administration are an obstacle to consistency and one of the greatest challenges, she said. New elected officials must assist, and continue to attend, UCAB meetings and realize this issue affects their constituents to this day, Herrera said.

Longtime southside residents and activists have expressed gratitude for the work the city and utility have been doing to fix the PFAS issue, regardless of nonexistent regulations. Yet there continue to be mixed feelings in the community.

Daniel Sullivan, an assistant professor at the University of Arizona who is researching the mental health effects of the Superfund site on Tucson’s southside residents, said some interviewees expressed the feeling that their experiences continue to be denied. For example, some residents feel they should have access to free or reduced health care for illnesses associated with the Superfund site, which has never materialized.

Officials saying there is nothing to worry about often seems a dismissal.

Herrera, who has lost numerous family members to severe illness, has heard researchers assert that the effects are not generational. Yet her parents' generation and her generation got severe health issues, as well as her siblings' children’s generation and their children. Stories of loss that echo across the neighborhood.

To many elected officials, what happened in southside Tucson decades ago is a “done” issue, Herrera said.

But it’s not, she said. Not until the water is clean.

Anyone interested in preserving groundwater quality and learning more about the process of removing TARP-area contaminants may attend a UCAB quarterly meeting. The next meeting is scheduled for Wednesday, Jan. 18, 5:45 p.m., at the El Pueblo Neighborhood Center, 101 W. Irvington Road.

Attendees can also join remotely using this link or call 213-379-9608 (passcode 144 125 347#).

Clara Migoya covers environment issues for The Arizona Republic and azcentral. Send tips or questions to clara.migoya@arizonarepublic.com.

Environmental coverage on azcentral.com and in The Arizona Republic is supported by a grant from the Nina Mason Pulliam Charitable Trust. Follow The Republic environmental reporting team at environment.azcentral.com and @azcenvironment on Facebook, Twitter and Instagram.

Support environmental journalism in Arizona. Subscribe to azcentral today.

This article originally appeared on Arizona Republic: Tucson's water contaminated by PFAS; health concerns amplified