Phoenix isn't what it once was because of climate change. But it's not too late to save it

I was born at John C. Lincoln Hospital in Phoenix when the global atmospheric concentration of carbon dioxide was at 343 parts per million and the population of the metro area was 1.7 million.

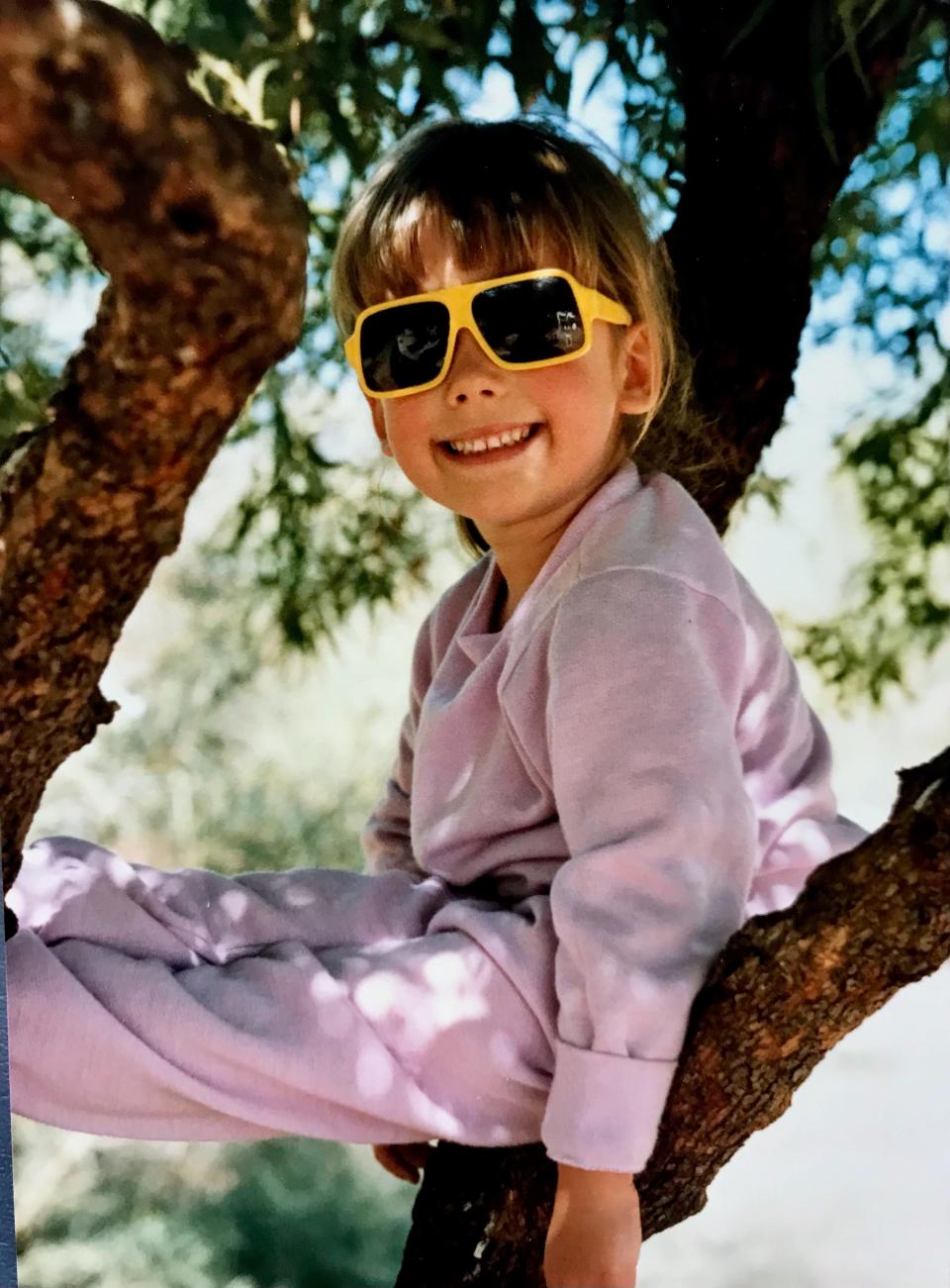

Since then, I have lived in many places. Since then, metro Phoenix has ballooned to nearly 4.7 million people, and counting. Since then, the tree in the front yard of my childhood home, in what used to be north Phoenix but has now been swallowed up by central Phoenix, the tree in whose branches I used to perch with my notebook and write stories about what I saw, has disappeared.

I return to Phoenix at an atmospheric carbon dioxide concentration of 418 ppm. Each additional molecule of carbon dioxide, along with those of other greenhouse gases industrialized humans and other sources have emitted into the atmosphere, absorbs energy and traps heat in this bubble dome we all call home, eventually changing what it means to live here.

In Phoenix, this is obvious. Over the past five decades (I’m not that old, but the data is), the average local summer temperature has increased by 3.6 degrees Fahrenheit (2 degrees Celsius). There are nine more days per year now when Phoenix logs a temperature over 110 degrees. And the average summer overnight low has risen by 5.5 degrees, offering less and less relief to Phoenix residents trying to stay in their desert homes. Air quality worsened by wildfires, access to sufficient water and rising food prices also pose challenges our grandparents didn’t have to consider. It’s a different world now.

This week the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change shared its sixth assessment from its Working Group II. In this report, top scientists from all over the world looked at the available evidence and predicted, to the best of science’s current ability, what the impacts and vulnerabilities of a warming climate will be in different habitats, and how we might be able to adapt.

More than 270 experts have been working, as volunteers, on this particular report since January 2019, when Phoenix’s population hadn’t yet passed 4.5 million and the global CO2 measured at 411 ppm.

The findings predict many things we already guessed: Drought in the West will worsen, wildfires will become more frequent and severe, average temperatures will continue to rise and already-vulnerable peoples will be the most vulnerable to it all.

Hotter summers, bigger fires, less water: How Arizona is adapting to new climate norms

On Sunday the secretary-general of the United Nations, António Guterres, called the new report "an atlas of human suffering and a damning indictment of failed climate leadership." He declared humanity in the midst of a "frog march" toward destruction.

It is too late to avoid all of the consequences of human-caused climatic change, the report found. Stronger, more erratic storms are on their way. Many species will be lost. Agriculture will have to change. Human migration away from uninhabitable deserts and rising seas will irreversibly shape the distribution of people on our planet, and likely the conflicts that arise between them.

But the report also spelled out hope. And Guterres expressed confidence that we can still limit emissions, transition to renewable energy, invest in adaptation, prepare workers for green jobs and work together as a global community to mitigate and prepare for what's to come.

If the staggering changes Phoenix has undergone since I left as a child prove anything, it is that we can change again. The rate at which this community, and the global one, has shifted and adapted to new technologies and lifestyles in recent decades is impressive. The challenge now is to make similar strides in a not-quite opposite, but a different direction.

A study published on Valentine’s Day in the journal Nature Climate Change found that 42% of the decline in soil moisture since the year 2000 can be attributed to human activity influencing a changing climate. The report's authors determined that the Southwest region of North America is currently in the worst drought of the past 1,200 years, since the year 800. If you have lived here long, you may have guessed this trajectory already.

It would make no sense to compare today’s average consumption of energy and fuel, or the mileage efficiency of modern modes of transportation to those used by people in the year 800, or to suggest that we return to some more sustainable past. Similarly, it may be hard now to imagine the extent to which common habits in the world could change in the future. But we created that change, or at least 42% of it since 2000. So we know we have the power to affect world-altering positive change now.

It won’t be easy. But neither was transitioning from horses to oil-burning engines to cars we can now recharge at increasingly available battery stations, or from messenger pigeons to emails. We can’t unbuild the metro area. And we can’t capture all the carbon we’ve put into the atmosphere since I sat perched in a tree in my Phoenix front yard as a child. There are innumerable false solutions.

But the IPCC report laid out some tangible solutions too. And Phoenix, with its blistering heat, withering soils and rapid population growth along with some of the best sunsets I've ever seen, is uniquely positioned to be a leader in sustainable building, renewable energy, agricultural advances and the purposeful reintegration of nature into our lives.

Report: Population growth brings greater climate risks to metro areas, but also hope

I don't know what kind of trees I climbed here as a child. The photos don't show enough detail to say for sure. It's likely I hung from the branches of Aleppo pines, Pinus halepensis, which used to cast shade across many more Phoenix parks and playgrounds than they do today.

Last June the Arizona Department of Forestry and Fire Management issued a Forest Health Alert, warning that "excessive summer heat is creating stressful conditions for mature Aleppo pines" in low elevation desert communities. The department advised homeowners to deep-water these "high value" trees through the summer months to keep them from succumbing to heat stress. Dropping reservoir levels at Lake Mead, however, make it pretty clear that Arizona doesn't have the water for this to be a complete solution.

The Aleppo pine has been a popular past landscaping choice in the Phoenix regionbecause of its sheltering stature, lush needles and the fact that it was thought to be well-suited to our dry climate and alkaline soils.

But it is native to the Mediterranean region. It's not a fully desert-adapted plant. And it's certainly not a record-breaking-drought-adapted plant. Not much really is. Horticulturists at the University of Arizona's Maricopa County Cooperative Extension now recommend people avoid planting Aleppo pines in their yards because they might not survive our climate future and can be expensive to remove.

While the Aleppo pine can't adapt at the pace that may be required by ongoing climate change, humans have many more options. The story of this century will be about whether or not we decide to take them.

That’s my story. Now I want to hear yours. I want to tell yours. How has the changing climate affected your life in Arizona? Have you experienced climate impacts in unexpected ways? Write to me at joan.meiners@arizonarepublic.com.

Joan Meiners is the climate news and storytelling reporter at The Arizona Republic and azcentral. Before becoming a journalist, she completed a Ph.D. in Ecology. Follow Joan on Twitter at @beecycles or email her at joan.meiners@arizonarepublic.com.

This article originally appeared on Arizona Republic: How Arizona climate's past, present and future affect Phoenix