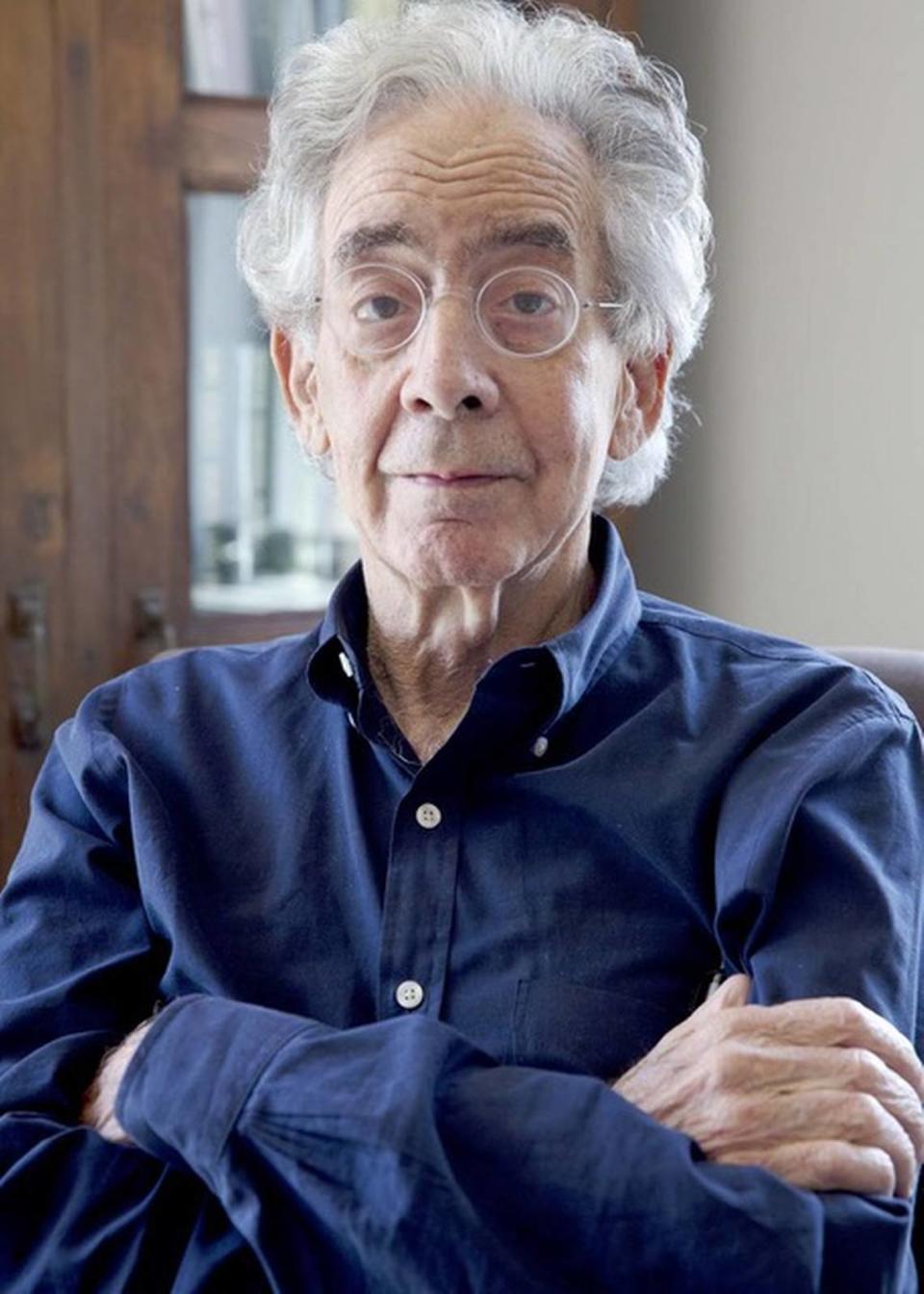

From ‘photo shacks’ to showcasing Miami: Educator, author Michael Carlebach dies at 78

Michael Carlebach worked long hours with his students, laboring together over vats of chemicals in darkrooms. He taught them the entire process, from taking the photo to admiring the final print.

A former student and now award-winning photojournalist, Brenda Ann Kenneally, stayed in touch with Carlebach long after leaving the classroom. Kenneally, the author of Upstate Girls, a years-long project centered in her home region of upstate New York, remembers that Carlebach was there (with a camera) at her wedding and her son’s christening, and he always kept on top of the awards she won for her work.

Carlebach — photographer, educator, mentor — died Aug. 22 at his home in Asheville, North Carolina. He was 78.

Carlebach as a scholar

Michael Carlebach began teaching photography at the University of Miami in 1978, and continued until 2005, mentoring hundreds of students until he retired and became professor emeritus.

Carlebach led the program with friend and fellow photographer David Kent. The culture of the program under Carlebach’s leadership was scrappy, communal, and driven by a real love for the art of photography.

Kenneally feels a sense of “impossibility” looking back on the program Carlebach ran at UM.

The photography classes were held in old, tucked-away Bahamian-style buildings, built during World War II and used as ROTC training grounds, Kenneally said. The program lovingly called the wooden buildings “photo shacks.” Though they weren’t in modern, airy buildings with ample space and resources, that didn’t matter to Carlebach and his students.

“We were the misfit nerds of photography,” Kenneally said. “We weren’t an art photography program. What we were going to do was not geared towards selling stuff. We saw truth. We were encouraged to go after it. This kind of program does not exist anymore.”

Carlebach’s educational philosophy stressed the importance of context in photojournalism. He taught his students not just how to take photographs, but also how to speak about them and share them responsibly.

“We weren’t just getting photography,” Kenneally said. “We were learning integrity as people, which couldn’t be separated from the work we were doing.”

Carlebach’s role as a scholar of photojournalism informed this contextual approach. He received his doctorate in American Civilization from Brown University in 1988, and authored nine books, including “American Photojournalism Comes of Age,” a historical account of the photographs and photojournalists who shaped American news in the early 20th century.

At UM, he directed the American Studies program and chaired the Department of Art History. During his time at the university, he won the Wilson Hicks Conference Award, the Freshman Teaching Award, Excellence in Teaching Award, and a Provost’s Award for Scholarly Activity.

To Kenneally, Carlebach was more than a teacher. He was a bridge to a new way of life.

After being in and out of the juvenile justice system and hitchhiking to Miami, Kenneally began studying photography under Carlebach. His mentorship led her to a career as a photojournalist.

“Michael,” she wrote in a scrapbook that former students gave Carlebach when he retired, “I can never thank the one who has allowed a commoner like me to walk among kings — photography has given me a life — you gave me photography.”

A survivor of illness

Carlebach was a survivor of multiple illnesses against all odds. As a child, he lost four siblings to cystic fibrosis, a condition with which he himself was diagnosed as an adult.

“That [loss] always hung over him and affected his worldview and his dark sense of humor,” said his wife, Margot, an architectural writer and historic preservation planner.

With cystic fibrosis, lung problems were always a part of his life. He survived infections of pneumonia and COVID, a doctor who mistakenly punctured his stomach with a feeding tube, and a double lung transplant in 2005.

The transplant drastically improved his quality of life, said his wife, giving him many more good years.

His son Joshua said that although his father wasn’t a big man, “boy, he could take a punch and keep coming.”

Alongside his freelance photography work, Carlebach made time each year to photograph the children at Nicklaus Children’s Hospital’s Ventilation Assisted Children’s Center sleepaway camp.

The camp draws children with respiratory issues from around the world to South Florida for a week of activities such as swimming, camping and games. As a volunteer photographer for the camp, Carlebach spent time with children who, like him, dealt with respiratory illnesses, and gave each family a printed portrait of their child at the end of the week.

The man in the darkroom

Those who knew Carlebach knew that he could often be found in a darkroom, either by himself or with students, developing photos by hand well before the digital downloading of today.

Though he grew up in upstate New York, raised on fishing and hiking in the woods, his influence as a photographer is particularly strong in South Florida.

Throughout his career as a photojournalist, Carlebach was a staff photographer for the Miami Herald and The Village Post in Coconut Grove. As a freelancer, he contributed to the Herald’s Tropic magazine, Time and the New York Times.

In 2010, Carlebach gathered a series of photos from his three decades in South Florida into a book, “Sunny Land: Pictures From Paradise.” The photos track the lives, culture and grittiness of a bygone South Florida: a woman diving into a Key West pool, Haitian refugees at the Krome detention center, demolition derby drivers in Hialeah.

In 2011, Carlebach donated images from his personal archives to the University of Miami Libraries’ Special Collections. Anyone can now view the 5,000 silver prints, color slides and publications of the Michael L. Carlebach Photography Collection. It includes images from George McGovern’s 1972 presidential campaign and the flora and fauna of the Everglades.

“I look for meaning at the edges of things,” Carlebach said on his personal website about his work, “avoiding the incendiary characters who bully their way into our lives whether we like it or not ... to see and appreciate what is subtle, funny or poignant right in front of us. That’s my job.”

Survivors and services

Carlebach is survived by his wife, Margot Ammidown; sons Adam and Joshua; brother Stevenson; grandchildren Dominic and Leed; his dog Addie, and a vast network of former students and mentees.

The family encourages donations in Carlebach’s memory to be made to the University of Miami Libraries Special Collections or the Cystic Fibrosis Foundation. His family hopes to hold services at UM at a later date to honor his life and work.