He photographed some of the ugliest Civil Rights moments, including Emmett Till’s trial

- Oops!Something went wrong.Please try again later.

- Oops!Something went wrong.Please try again later.

History can be erased or obscured if nothing is done to prevent it. This is particularly true for Black history. And this is where Ernest Withers’ photography steps in.

“It provides historical truth and visual proof that African-American history and its culture are important,” says Rosalind Withers, Ernest’s daughter and director of the Withers Collection Museum & Gallery in Memphis.

Withers’ photography is on display through Thursday, Aug. 31, at The Arts and Recreation Center (The ARC), in Opa-locka, in an exhibition titled “Flash Points: The Photography of Ernest C. Withers.”

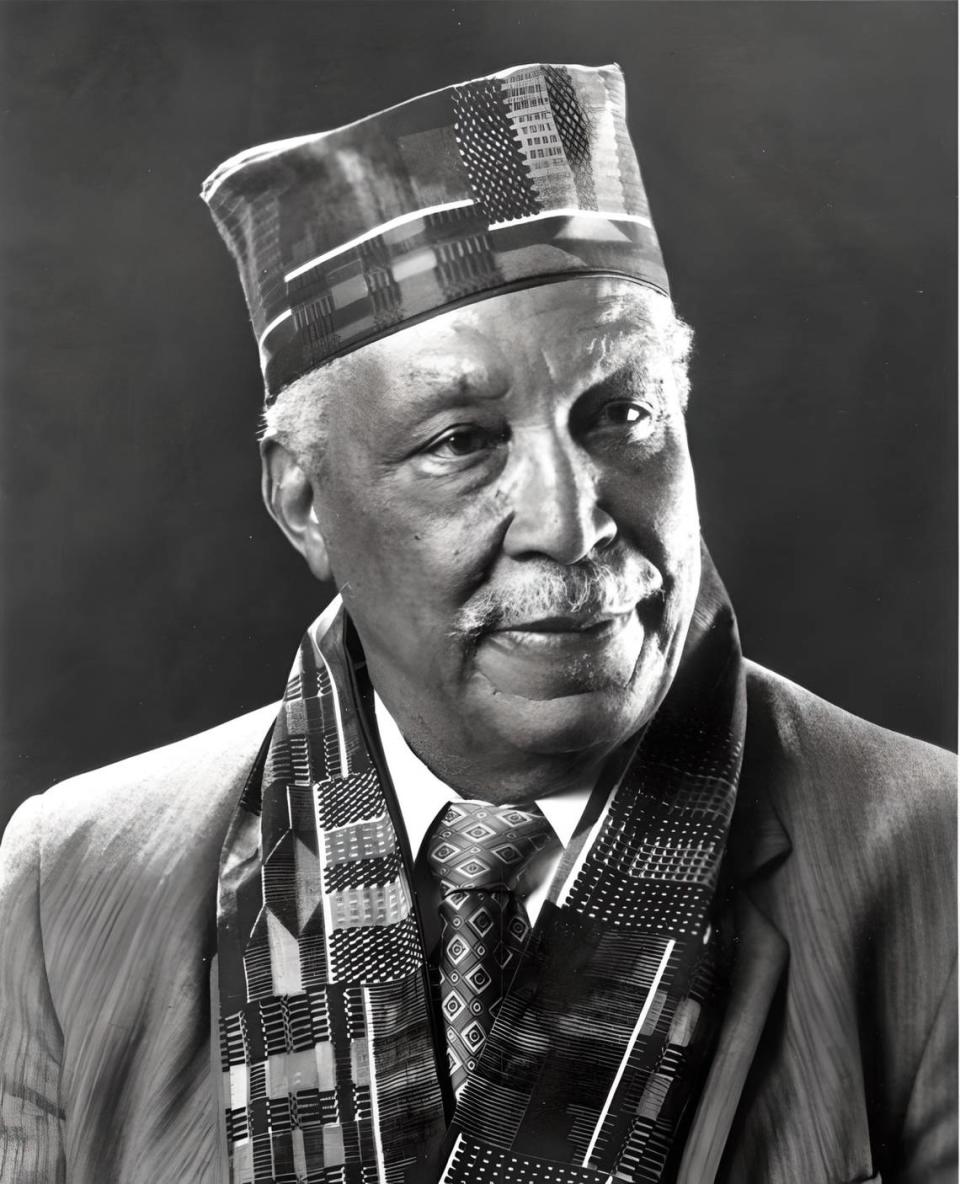

Curated by Ten North Group, in partnership with Rosalind Withers, the exhibit showcases 41 photographs by Memphis-born African-American photojournalist Ernest C. Withers, who documented pivotal moments of the Civil Rights Movement.

Born in 1922, he died at the age of 85 in October 2007 in Memphis. The exhibition is representative of his 60-year career and features striking images from the nation’s Civil Rights battles, including the Montgomery, Alabama, bus boycott of 1955-56; the Memphis ‘I AM A MAN’ sanitation strike; and the 1955 Sumner, Mississippi, murder trial of Emmett Till. (The Rev. Martin Luther King had gone to Memphis to support the sanitation workers’ strike, which led to his assassination in Memphis on April 4, 1968.)

“These images reflect people and communities at the precipice and center of change. We see people actively working toward resisting oppression. working toward self-preservation in a world that has discarded, discounted and devalued them,” says Joel Diaz, director of the Ten North Arts Foundation and the co-curator of Flash Points.

Withers’ images capture the intimate portraits of the Southern landscape during the Civil Rights era, Diaz said. Many of the moments are documented in large part because of Withers’ photography, he adds.

“In Flash Points,” Diaz continues, “the images — presented alongside one another — provide a chronology of the events that ushered forward new experiences for Black Southern people. The black-and-white film photographs hold emotive sensitives, tensions and commemorations that together offer a visual language of the era.”

The exhibit focuses on historical moments that ignited actions and ultimately influenced outcomes within the Civil Rights Movement. It features images of Tent City in Fayette County, Tennessee, the result of voter registration/suppression efforts in the early 1960s that led to the evictions of many of Fayette County’s Black residents.

Took photos at Emmett Till murder trial

“Flash Points” also features images of the desegregation of Central High School in 1957 in Little Rock, Arkansas, and the Memphis Thirteen, a group of 13 African American first graders who integrated Memphis schools in 1961.

The exhibit also showcases photographs depicting the aftermath of 14-year-old Emmett Till’s murder in 1955. He was kidnapped, tortured and shot in the head, his body dumped from the Tallahatchie River Bridge in Mississippi. Withers stood as one of the few photographers to visually record the trial proceedings.

The “Flash Points: The Photography of Ernest C. Withers” exhibit is happening in a particular context for Black history in Florida.

“Currently, the Florida state governor has made it clear that African-American history and culture should not be taught in any educational platform to the constituents of his state. He feels that African-American history is not significant,” says Rosalind Withers.“That’s not the case. This exhibit is clearly to exemplify the importance of letting the public know that this history exists — that this is not just African-American history, it is American history.”

In February 2011, Rosalind Withers established the Withers Collection Museum & Gallery with the purpose of safeguarding her father’s pictorial legacy.

Rosalind noted the importance of imagery and how it can change the course of history. She cited the George Floyd video that went viral two years ago and sparked protests around the world.

“Imagery,” she explains, “is profoundly important. It is something that is etched in people’s minds. And when you get that etched in people’s minds, it’s not something that is erased. It’s something that is retained. And the world in which we live in today, that world lives on imagery.”

Photographing Negro Leagues players

Ernest Withers’ lens not only documented the Civil Rights Movement but also immortalized legendary figures in the realms of entertainment and sports. Within the music industry, he captured artists who were then striving to establish themselves, including Al Green, Tina Turner, B. B. King and Isaac Hayes.

His portfolio extended to the world of sports, encompassing shots of Jackie Robinson, Satchel Paige, Roy Campanella, Ernie Banks and others who played baseball in the Negro Leagues.

While the exhibition features only 41 images from Ernest Withers’ body of work, the collection is quite extensive since it spans over six decades.

Rosalind Withers, entrusted with the guardianship of her father’s legacy, said the entire collection encompasses a minimum of 1.8 million images. Only a fraction of these images, specifically less than 1 percent amounting to around 17,000 photographs, have been digitized to date.

“For me personally, when I first got the responsibility as being his trustee, I had to walk into the room where his whole body of work was. And it was just very daunting. You walked in there, it just looked like a mass of material that was just everywhere, and it was endless,” she says.

But the work is important, she said, as it documents history. She noted the Black Wall Street massacre in Tulsa, Oklahoma, and attempts to bury that history. The massacre began during the Memorial Day weekend in the Tulsa neighborhood of Greenwood in 1921. But it wasn’t until 1996 that the Oklahoma Legislature authorized a formal investigation into the tragedy, which resulted in hundreds of Black residents killed, their homes and businesses destroyed.

“But guess what? There were some photographs that were found, and those photographs helped to bring that story to life. And that’s the beauty of this body of work. You can say that our history is not important, but when we have proof of our history, you can’t erase it.”

WHAT: ‘Flash Points: The Photography of Ernest C. Withers’

WHEN: Through Thursday, Aug. 31

WHERE: The Arts and Recreation Center (The ARC), 675 Ali Baba Ave, Opa-locka, FL 33054.

COST: Free

INFORMATION: 305-687-3545 or olcdc.org/flash-points

ArtburstMiami.com is a nonprofit media source for the arts featuring fresh and original stories by writers dedicated to theater, dance, visual arts, film, music and more.