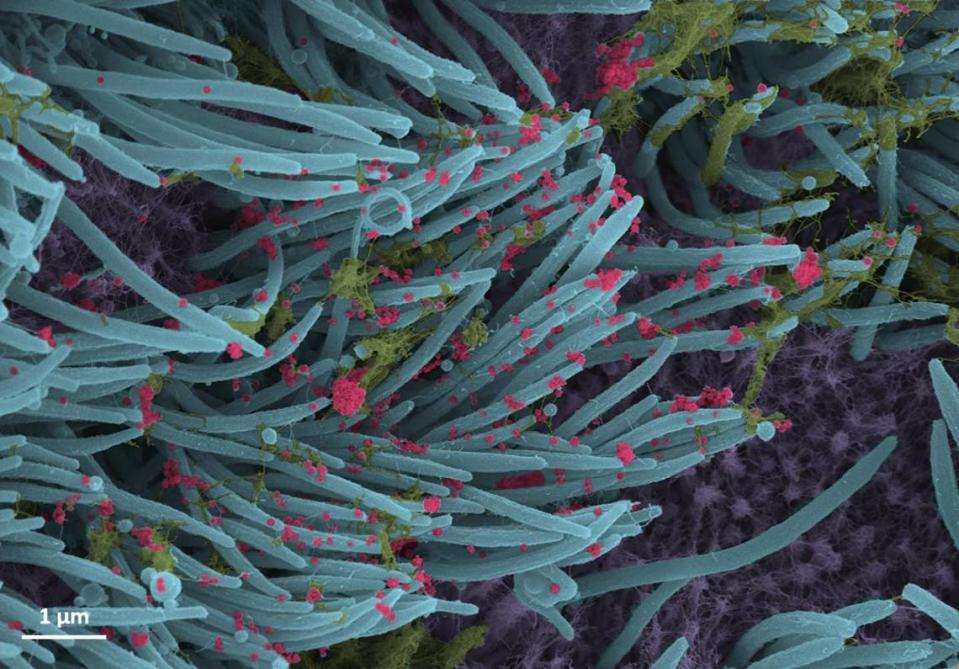

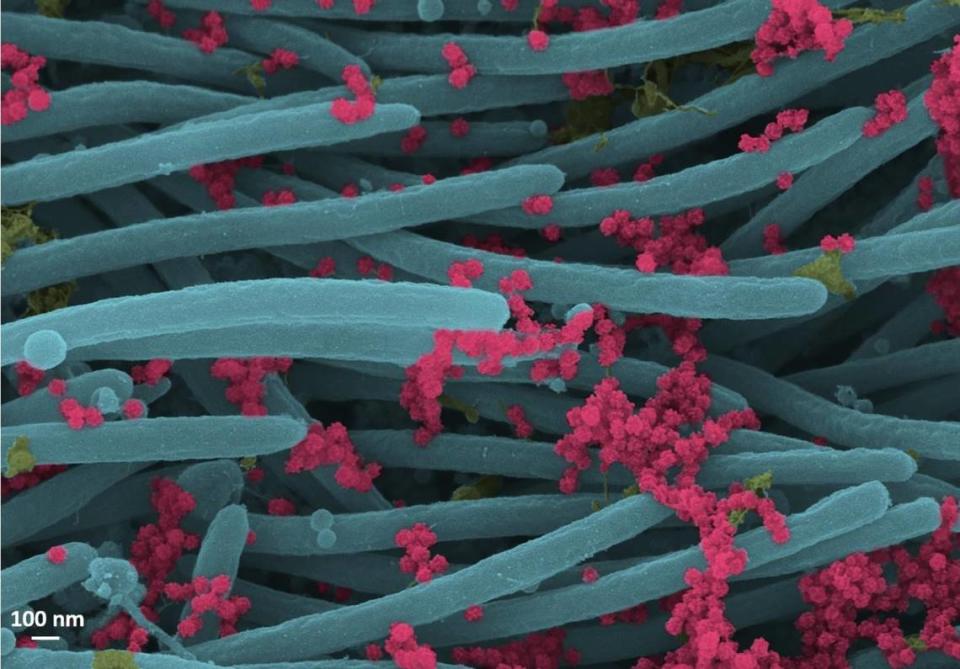

Photos of coronavirus attacking lung cells show how ‘intense’ infections can get

New detailed images of lung cells under a special microscope illustrate how “intense” a novel coronavirus infection in the airways can be, according to researchers from the University of North Carolina, Chapel Hill. The photos provide a visual explanation behind the rapid spread of SARS-CoV-2.

The snapshots show red-colored coronavirus particles glued onto the blue tips of ciliated cells, or spaghetti-like structures that line the surface of a human airway. These ciliated cells help transport mucus (pictured in yellow), dust and trapped viruses and bacteria up and out of the lungs.

To capture the images, researchers infected lung cells with the coronavirus in a laboratory, according to Dr. Camille Ehre, a pulmonologist and assistant professor of pediatrics at UNC School of Medicine. They revisited the cells 96 hours later and examined them using scanning electron microscopy.

“This imaging research helps illustrate the incredibly high number of virions (infectious forms of the virus) produced and released per cell inside the human respiratory system,” the researchers said in a Sept. 10 news release. “The large viral burden is a source for spread of infection to multiple organs of an infected individual and likely mediates the high frequency of COVID-19 transmission to others.”

“These images make a strong case for the use of masks by infected and uninfected individuals to limit SARS-CoV-2 transmission,” the researchers added.

To prevent further coronavirus spread, the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention recommends wearing a face mask over your nose and mouth when around others.

The photos were published Sept. 3 in the New England Journal of Medicine’s section called “Images in Clinical Medicine.”