New Photos of Pluto and Moon Surprise, Puzzle Scientists

The first up-close images of Pluto and its biggest moon, Charon, are making scientists rethink the inner workings of these and other icy, far-flung worlds.

The new Pluto photos, which were captured by NASA's New Horizons spacecraft during its historic flyby on Tuesday (July 14), show that both the dwarf planet and Charon have been geologically active in the recent past.

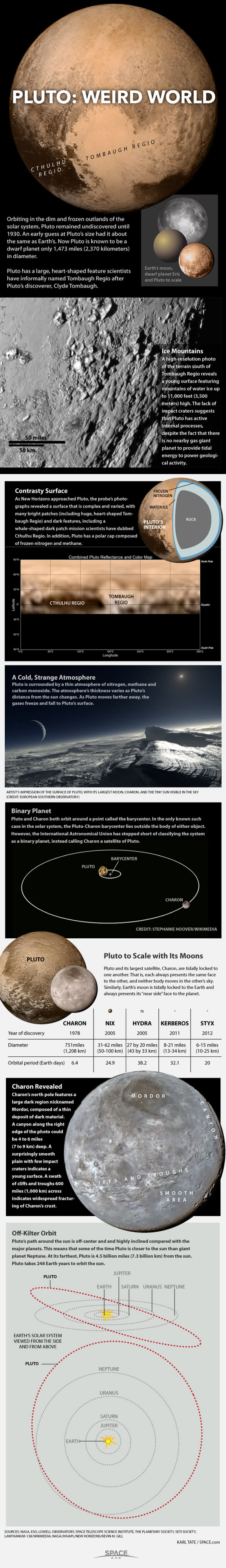

Pluto harbors giant ice mountains, for example, while miles-deep chasms score Charon's surface. And craters are surprisingly scarce on both bodies, indicating that they've been resurfaced relatively recently. [Watch NASA Unveil New Pluto Photos (Video)]

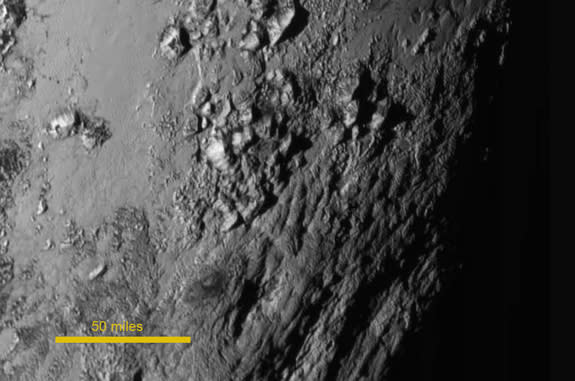

"The most striking thing about this image is, we have not yet found a single impact crater on this region," John Spencer, of the Southwest Research Institute (SwRI) in Boulder, Colorado, said during a news briefing Wednesday (July 15), referring to the newly released photo revealing Pluto's ice mountains.

"Just eyeballing it, we think it has to be probably less than 100 million years old," added Spencer, the deputy leader of New Horizons' geology and geophysics investigation (GGI) team. "It might be active right now. With no craters, you just can't put a lower limit on how active it might be."

Indeed, the 1 percent of Pluto captured by the new photo "is one of the youngest surfaces we’ve ever seen in the solar system," fellow GGI team member Jeff Moore, of NASA’s Ames Research Center in Moffett Field, California, said in a statement.

Signs of recent or ongoing geologic activity have been spotted on other smallish bodies in the solar system, including Saturn's geyser-spewing moon Enceladus and the extremely volcanic Jovian satellite Io. But the interiors of these latter objects are warmed as a result of gravitational tugs from their huge parent planets, in a process known as tidal heating.

"That can't happen on Pluto, because there is no giant body that can deform it on a regular basis," Spencer said. "This is telling us that you do not need tidal heating to power geologic activity on icy moons. That's a really important discovery that we just made this morning."

Pluto and Charon aren't tugging hard on each other, either, and haven't for eons.

"Pluto and Charon are in tidal equilibrium," said New Horizons principal investigator Alan Stern. "Charon orbits in the equivalent of geosynchronous orbit, and it is also spinning at the same rate that Pluto spins. So there is no significant exchange of tidal energy anymore."

Furthermore, the heat generated by the mammoth, long-ago collision between a proto-Pluto and a proto-Charon, which is thought to have shaped the system, likely dissipated in the ancient past, mission team members said.

So the evidence of recent activity on Pluto and Charon comes as quite a surprise. Mission scientists aren't sure what has been powering this activity — they just saw the new photos for the first time on Wednesday, after all — but a couple of possibilities spring to mind.

For example, Pluto and Charon may have held onto their interior radioactive heat for much longer than scientists had thought possible. (Heat from radioactive decay is still a force here on Earth, but our planet is far bigger than Pluto and Charon, which are about 1,470 miles [2,370 kilometers] and 750 miles [1,200 km] wide, respectively.)

"This may be telling us that, even very small bodies, if they're icy — radioactive heat is enough to produce this activity," Spencer said.

It's also possible that Pluto and Charon possessed subsurface oceans that froze very slowly, releasing heat into the bodies' crusts over time, he added.

"Whether the heat generation is ongoing or it’s still living off this reserve of stored energy from its formation, that's for a lot more work to decide," Spencer said of Pluto.

The discovery that even relatively diminutive Charon was geologically active not too long ago makes Pluto's distant realm, known as the Kuiper Belt, and its many denizens even more intriguing, Spencer said.

"I think we've tended to think of these mid-sized worlds — Makemake, those kind of objects — as probably candy-coated lumps of ice," he said. "This means they could be equally diverse and equally amazing, if we ever get a spacecraft out there to see them close up."

Follow Mike Wall on Twitter @michaeldwall and Google+. Follow us @Spacedotcom, Facebook or Google+. Originally published on Space.com.

Copyright 2015 SPACE.com, a Purch company. All rights reserved. This material may not be published, broadcast, rewritten or redistributed.