How pianist James Williams altered my life's path

On the phone, James Williams would often greet me with an ebullient “What’s up Daddy-O?” Followed by “When are you coming to visit the greatest city in the world?”

Several birthday well-wishes contributed to the “In Memory of James Williams” Facebook group page tells a good part of the late pianist’s story: his generosity, positivity and what he still means to jazz community.

The posts from several of the more-than-600-member group arrived in recognition of what would have been Williams' 72nd birthday on March 8. The proud Memphis native, turned avid New Yorker, succumbed to cancer as a 53-year-old on July 20, 2004.

Yet 19 years after his passing, there remains an annual outpouring of love and affection for Williams. Accomplished jazz musicians comprise almost half the Facebook group — many shared the stage and recorded with the pianist, many incorporate Williams’ noteworthy contributions into their work.

We also are fortunate that William Paterson University, in Wayne, N.J., whose jazz department Williams directed from 1999 until his death, archived his quite substantial work, despite a career tragically cut short.

Williams is likely the number one reason I became involved with the jazz industry. That’s different than simply being a fan of the music.

I saw and got to know Williams in the mid-1970s, having heard him play in a variety of configurations, mostly in New York City. There were his solo, duo and trio dates, as well as overlapping stints with the likes of trumpeter Art Farmer and saxophonist Benny Golson, including during his four-year stint (1977-1981) as a member of Art Blakey’s Jazz Messengers — where he met and worked alongside Bobby Watson.

I arrived in Columbia in August 1978. In the mid-1980s, still a fairly recent University of Missouri School of Journalism graduate with my master's degree, I managed to sell DownBeat magazine on a profile on Williams. In the midst of researching and contacting Williams, Murry’s had recently opened. Former owners Gary Moore and Bill Sheals — two friends and fellow jazz lovers — inquired if any of the players I was covering would be willing to perform at the restaurant. I had no idea but said I would ask.

The Williams profile provided me with that opportunity. Little did I know it would radically alter my life.

In September 1985, Williams became the first nationally-known artist to play at Murry’s. It fell on me to drive him to the airport. On the way to St. Louis, Williams held the tape recorder microphone. I asked him questions and he loquaciously answered them, providing me with the sought-after material.

Upon his return to New York, Williams, a fixture on the scene, spoke positively about his Murry’s experience. Within days my phone began to ring, calls arriving from numerous artists I had seen perform. These were “famous people," some of the world’s best musicians. Initially, I was taken aback, but realized the outgoing Williams must have spread the word.

To quote Humphrey Bogart in “Casablanca," it was “the start of a beautiful friendship.” I began to represent and often go on the road with groups led by or including Williams. Knowing and working with “J.W.,” as I often called him, provided me with entrée into what I consider an extremely special world, one not to be taken for granted.

Williams, also an entrepreneur and producer, did not shy away from larger projects. Among his groups was I.C.U. — Intensive Care Unit — a jazz-meets-gospel ensemble. The septet featured two saxophonists, a piano-bass-drums rhythm section and two vocalists. While the challenges of landing performances for that ensemble seemed measurable, the Williams-concocted Contemporary Piano Ensemble took logistics to an entirely different level.

The group served as an homage to both Memphis and its iconic native son Phineas Newborn Jr. Williams, Harold Mabern and Donald Brown, fellow Memphis natives and pianists, along with pianists Mulgrew Miller — Williams’ college roommate — and Geoffrey Keezer took to the road with four Yamaha-provided grand pianos plus bassist Christian McBride and drummer Tony Reedus, Williams’ nephew. Traveling with the pianos, the group held 19 concerts in 23 days, including one at the Missouri Theatre.

Between 1995 and his 2004 passing, Williams made several “We Always Swing” Jazz Series appearances, again, appearing in a number of configurations.

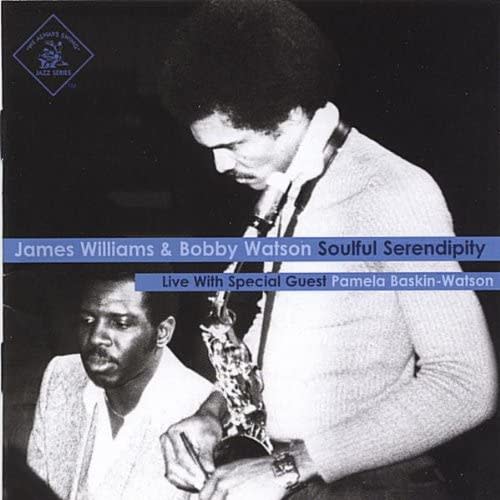

His final recording — a duo with saxophonist Watson, with Watson’s wife Pamela Baskins adding a vocal track — served as a Jazz Series “House Concert”-fundraiser. The date: June 14, 2003.

This was not a pre-determined recording. Titled "Soulful Serendipity," microphones were hurriedly placed when, on the way from the hotel to the host home, Williams and Watson discovered that despite sharing a stage thousands of times as Jazz Messengers and throughout their careers, they had never played as a duo.

When Williams died 13 months later, releasing the recording became a desire. Watson agreed to sequence selections; the Jazz Series produced the recording, with net proceeds going to its education programs, named after Williams several years earlier. The recording, which included in-depth descriptive liner notes and musician comments, was released nationally in 2006.

J.W. — Happy No. 72.

What other artists thought of Williams, from the "Soulful Serendipity" liner notes

“I called him ‘The Historian’ because he knew so much about the music and the musicians who played it.”

— Marian McPartland

“In all the years I knew James, he never let the realities of the ups and downs of a jazz life affect his warmth and kindness to his fellow colleagues. His demeanor made quite an impression on me as I grew up in New York. He was a marvelous talent, but even more so a marvelous man."

— Branford Marsalis

“The first time I met James was when I was in high school. He was playing with Dizzy’s (Gillespie’s) Big Band. We were big James Williams fans ... we knew all of James’ tunes.”

— Christian McBride

“James was one of my closest friends from the time we met in 1968 at band camp. I was 14 and James was 17. We were best buddies right from the start."

— Pat Metheny

Jon W. Poses is executive director of the “We Always Swing” Jazz Series. Reach him at jazznbsbl@socket.net.

This article originally appeared on Columbia Daily Tribune: How pianist James Williams altered my life's path