'The Picture Taker': What to expect in Ernest Withers documentary on PBS

- Oops!Something went wrong.Please try again later.

“Be what you is, because if you ain’t what you is, you is what you ain’t.”

“The Picture Taker,” a new documentary feature film, begins with this folksy advice from the artist of its title, the late Ernest Withers, who seems to be telling the audience: “Be yourself.”

But the comically worded contradiction of the quotation takes on ironic significance as the documentary progresses and reveals that the celebrated photographer was both entirely himself and not what he seemed.

Withers, whose camera gave him unquestioned access to African American society at every level, was the ubiquitous recorder of Black culture and history in Memphis and the South. He also was an FBI informant at the height of bureau director J. Edgar Hoover’s campaign against Dr. Martin Luther King Jr. and the civil rights movement. To quote two of the film’s witnesses: “The chronicler of our community” was also “a paid snitch.”

That’s not exactly news. It hasn’t been new since 2010, when The Commercial Appeal first reported that Withers was providing photographs, oral reports and other forms of “intelligence” to the Federal Bureau of Investigation as it tracked Black “radicals” in Memphis and beyond.

But what’s striking about “The Picture Taker” is its pertinence, even as it recycles iconic photographs and revisits historic events from many decades past. “Ernest’s photographs may be rooted in time but they are relevant to today,” said Los Angeles-based veteran documentarian Phil Bertelsen, the film’s director, in a recent interview.

Memphis history:Marker honors Memphis home of iconic Civil Rights photographer Ernest C. Withers

A snapshot of history: Rare color photos show 1968 Freedom Train in Memphis

If anything, the issues raised by the film — the relationship between law enforcement and the Black community; Withers’ status as a former police officer; the value of photographs that capture Black artistry and achievement but also provide evidence of state violence against Black bodies — have been amplified, tragically, by the Jan. 10 death of 29-year-old Tyre Nichols three days after he was beaten by Memphis police.

The film was completed in the wake of the Black Lives Matter protests, but it did not make its PBS debut until Jan. 30, as part of the “Independent Lens” documentary series.

“Obviously, that was done without the expectation that Memphis would be reeling from this incident of police misconduct,” Bertelsen said. “Again we learn that the past is prologue, and the more we ignore the past the more we’re destined to repeat it.”

Before its television launch, “The Picture Taker” made its debut in Withers’ hometown on Oct. 19 at the Halloran Centre, as the opening night film of the 25th annual Indie Memphis Film Festival. Some other festival and special theatrical screenings followed, but the film always was expected to find its largest audience via public television. It currently can be streamed through PBS on-demand.

A project literally years in the making, “The Picture Taker” was initiated by Bertelsen’s colleague and mentor, documentarian St. Clair Bourne, as an appreciation of Withers’ career, before the FBI connection was made public.

Bourne, 64, died just a little over two months after Withers' death at the age of 85 on Oct. 15, 2007. By that time, Withers, with his trademark kufi cap and dapper mustache, was an avuncular Memphis legend, embraced by all segments of the city; news of his death dominated The Commercial Appeal's front page, which carried the headline, in large bold letters: "Famed Photographer Dies."

With producer Lise Yasui of Philadelphia as a collaborative partner, Bertelsen took Bourne's baton and eventually resurrected the Withers project, which had become complicated by the FBI revelations. (Bertelsen, incidentally, also is one of the directors on the six-episode series “The 1619 Project,” which debuted last month on Hulu.)

A compact but thorough 80 minutes, "The Picture Taker" is a biography of Withers (born in Memphis in 1922) that argues for his significance as a photojournalist and artist while simultaneously presenting a history of Black Memphis and the regional civil rights movement, as witnessed in large part through Withers’ camera lens.

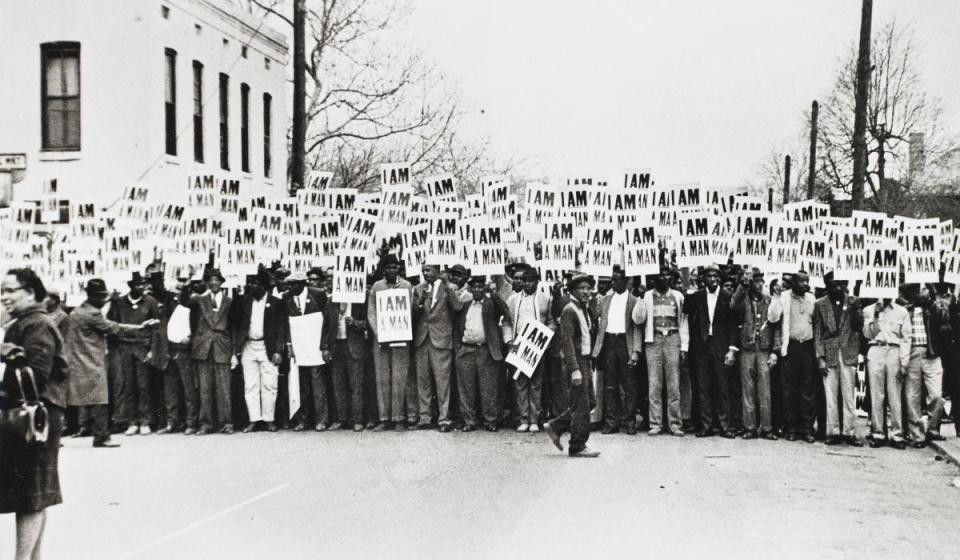

Withers chronicled the 1955 trial of Emmett Till’s alleged killers in Sumner, Mississippi; he covered the Montgomery bus boycotts; and he captured both intimate and epic images of King and his associates during the 1968 Memphis sanitation strike. He also shot church services, social events, Negro League baseball games, and club shows and visits by such stars as B.B. King, James Brown and Elvis Presley. The mostly black-and-white images offer an invaluable record of bygone people and places but also have their own beauty and humor and melancholy and mystery.

As a working photographer with a wife and large family, Withers shot pictures “from sunup to sundown, ten to 12 jobs a day, 365 days a year,” said daughter Rosyln Withers, in a recent interview.

Black history in Memphis: 5 landmarks you should know and the stories behind them

From the community:The brutal death of Tyre Nichols: horror, grief and lessons learned | Norment

Roslyn was the youngest of nine Withers children and the founder of the Withers Collection Museum & Gallery (open Tuesdays through Sundays on Beale Street). “The only time my father was not out on the streets was Saturday morning, because my mother made a big breakfast," she said.

Although Withers’ images of Black Memphis are his legacy, he also often photographed white movers and shakers. “He could navigate through different segments of the society,” former Memphis mayor Willie W. Herenton says in the film. “His camera was his passport.”

The documentary features interviews with many key figures in the Withers/Memphis story in addition to Herenton. These include former police colleagues (Withers in 1948 became one of Memphis’ first nine Black police officers, so his link to law enforcement predated his FBI work by over a decade); civil rights leaders; members of the local “Black Power” group, the Invaders; and several writers, including investigative reporter Marc Perrusquia, who broke the Withers FBI story while he was at The Commercial Appeal and then wrote the book “A Spy in Canaan: How the FBI Used a Famous Photographer to Infiltrate the Civil Rights Movement,” and Preston Lauterbach, whose book is “Bluff City: The Secret Life of Photographer Ernest Withers.”

Some of the interviewees say Withers was essentially a trickster who exploited the FBI by taking the bureau’s money for intelligence that was not particularly valuable. Others say he betrayed the movement by cooperating with its enemies. “We went to great lengths to leave it up to the audience to decide,” Bertelsen said. “To not make him a hero or a heretic.”

Roslyn Withers said her family was surprised by the FBI revelations, but eventually decided that her father simply was trying to navigate a complicated and dangerous world to the best of his and his family's advantage.

“My father left a legacy that is huge,” she said. “We’ve got 60 solid years of work and 1.8 million images, covering pivotal, historical shifts and the important movements of the times. We should not lose the focus on this record because of a historical flaw. Do we decide not to look at a Picasso because of his character flaws?"

This article originally appeared on Memphis Commercial Appeal: 'The Picture Taker': Ernest Withers documentary now on PBS