Piercing the propaganda veil: US, Schwarzenegger, hackers give Russians uncensored view of Ukraine war

- Oops!Something went wrong.Please try again later.

- Oops!Something went wrong.Please try again later.

WASHINGTON – Vladimir Putin isn’t a big Twitter guy.

The Russian leader follows just 22 people on his official English-language Twitter account. One of them is Arnold Schwarzenegger.

The Hollywood actor and former California governor is widely popular in Russia, so when he posted a video message to “my dear Russian friends” on social media last week about the brutal war in Ukraine, the Russian people – and presumably Putin – took notice.

“There are things that are going on in the world that are being kept from you – terrible things that you should know about,” the actor said in a nine-minute plea to Russia's government, military and citizens to end the fighting.

Schwarzenegger’s video message – distributed on the Telegram social media app, which is still accessible in Russia – is one of the ways that outside groups are piercing the veil of propaganda in a country that has clamped down on independent news organizations and blocked access to many Western-run sites like Facebook and Instagram.

As President Joe Biden and other NATO leaders prepare for a summit in Brussels on Thursday to discuss their response to Russia’s unprovoked invasion of Ukraine, the U.S. government and outside groups are waging an unofficial campaign to try to give Russians an uncensored view of the war.

Schwarzenegger’s message was shared by Russian opposition leaders on Telegram.

“Lots of people talked about it,” said Andrei Soldatov, a London-based Russian investigative journalist whose own website was blocked by Russian authorities on Sunday.

Suddenly, “you've got pro-Kremlin people attacking Schwarzenegger, and it didn't go well,” Soldatov said. “You can’t attack Schwarzenegger. It's a bad idea.”

'Actual, factual, truthful information'

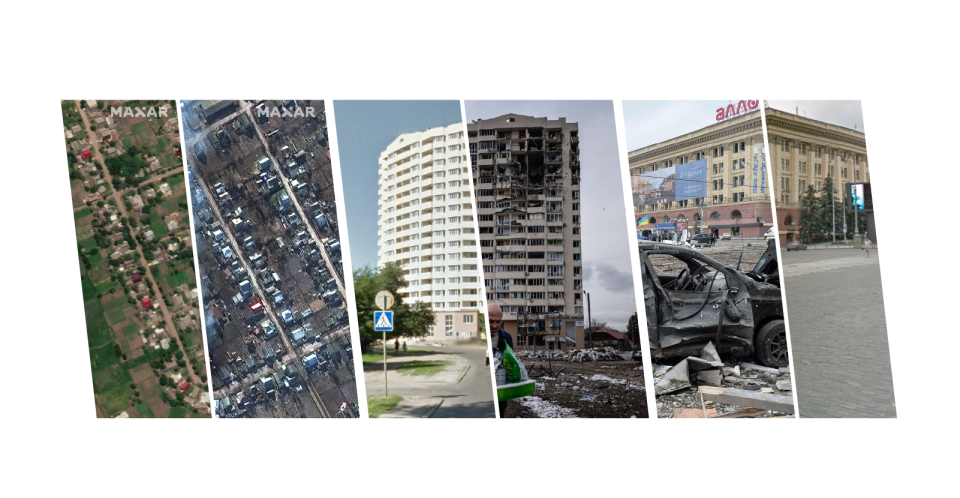

Viewers of Russia’s state-controlled TV news networks are fed daily accounts of the conflict that bear little resemblance to reality.

Use of the word “war” is forbidden, so they’re told that the “special military operation” is going as planned, that Russian soldiers are liberators, that Ukrainians are Nazis who are attacking their own people and blaming Russian troops, according to groups monitoring Russian television.

Images of Russian military hardware destroyed by Ukrainians are dismissed as “fake news.” False stories are spread about U.S. actions, including disinformation about Americans working with Ukraine to develop biological weapons for use against the Russians.

And now, pro-Putin activists are putting together lists of “traitors” and “enemies” on Telegram social media. The lists include dozens of journalists, singers, musicians, theatre and film directors, politicians, businessmen and internet bloggers.

The State Department’s chief spokesperson, Ned Price, said U.S. officials are “trying to get creative” in finding ways to reach out to Russian citizens with accurate information about the war but conceded it’s getting more difficult by the day.

“We have undertaken a concerted effort, through means that are available to us, to do everything we can to get actual, factual, truthful information into what is a pretty closed Russian information ecosystem,” he said during a March 15 briefing with reporters.

Price specifically cited the State Department’s use of Telegram, a cross-platform instant messaging service. But he did not say what kinds of messages the U.S. was sending or whether they were having any impact piercing Putin’s propaganda machine.

“It’s a challenge when it comes to Russia because President Putin and the Kremlin, they are doing everything they can to further constrict the information space throughout the country,” Price said.

PUTIN 'WON'T STOP' WITH UKRAINE: Why Americans should care about Russia's aggression against its neighbor

Putin clamping down on the free press

Earlier this month, the Russian parliament passed a law barring the spread of what the Kremlin calls “fake news” about the military assault on Ukraine. The penalty: up to 15 years in jail.

Kremlin authorities also mandated that Russian journalists refer to the assault as a “military operation of demilitarization," essentially banning the term "war." Some independent media outlets ignored the censors’ demands and were quickly shut down.

Access to other sources of information, including Facebook and Twitter, has been restricted, and Moscow blocked the U.S. government-funded Voice of America and Radio Free Europe/Radio Liberty, among other outlets.

During a March 8 hearing before the Senate Foreign Relations Committee, lawmakers pressed a top State Department official about how the U.S. is “penetrating the Kremlin's information firewall,” as Sen. Rob Portman, R-Ohio, put it.

Putin has choked off what was left of the free press in Russia because he was “so scared” of the flow of information coming from Washington and other Western capitals, said Victoria Nuland, the State Department’s undersecretary for political affairs.

Nuland said the State Department is working with Russian journalists and influencers who are outside the country but still able to get their information into Russia by various means.

The U.S. also is still getting information into Russia through Radio Free Europe/Radio Liberty even though Putin has shut the station down inside Russia, she said.

The outlet has a “relatively sizable” audience through its website, Nuland said, and Putin hasn’t shut down the internet – yet.

Analysts say that isn’t likely to happen because unlike China, which has restricted internet access for decades, Russia doesn’t have the infrastructure in place to erect a firewall comprehensive enough to choke off the flow of information online.

'WAR CRIMINAL': As Biden gets personal with Putin, US, Russia relationship hits a dangerous crisis

'A high degree of literacy'

Meanwhile, hackers and computer programmers have entered the cyberwar campaign to get the truth to the Russian people.

A group of Polish programmers has created a website, Squad303, that allows people from all over the world to directly message Russian citizens. When users click on a link, the site allows them to send a message to a Russian phone number or email address randomly selected from a database of 20 million cellphone numbers and 140 million email addresses.

The group said on Twitter that some 2 million messages were sent to the Russian people within 24 hours of the website going online. The Wall Street Journal first reported Squad303's activities.

Other groups are circumventing Russia’s blockade of outside voices by communicating with people inside the country over virtual private networks, or VPNs, which provide a private online connection between users and enable them to hide their online activity.

Russians have been using VPNs for years, “so even with the shutting down of sites like Facebook and Instagram, people in Russia have knowledge and are able to circumvent the government’s crackdown on the internet,” said Sam Woolley of the Center for Media Engagement at the University of Texas at Austin.

“All of the social media applications that we know in the United States are accessible in some way, shape or form in Russia – it just depends upon how savvy of an internet user you are,” said Woolley, who has researched the use of social media to manipulate public opinion.

Over the past couple of decades, some Russians have gotten used to accessing mainstream platforms or social media sites such as Facebook, “and when accessibility is taken away, Russians have become quick to learn how they can gain access to these sites and applications again,” Woolley said.

The biggest deterrent to retrieving forbidden information is the fear of repercussions, not lack of access, Woolley said.

Still, despite all the workarounds, the Kremlin’s propaganda machine is pervasive inside Russia, and older generations in particular rely on the country’s state-sponsored television for their news. That makes it very difficult for many Russians to get an accurate sense of what is happening in Ukraine.

'A BRUTUS IN RUSSIA?": Lindsey Graham called for Putin's assassination. Even discussing it brings danger to US, experts say.

'This is not fake'

Anti-war protests in Russia give outsiders hope that the truth is breaking through.

Russians have staged demonstrations in dozens of cities across the country since the start of the war. At one of the protests, the mother of a Russian soldier who carried a banner that read “No to War!” said she recognized her wounded son in one of the videos that the Ukrainian military has been posting on Telegram and Vkontakte, another social media platform broadly used by Russians.

“I want people to understand, this is not fake – here is my son, here I am, his mother,” the woman told reporters. “People wrote to me yesterday: ‘Prove that this is your son.’ I don’t want to prove anything. He is my son.”

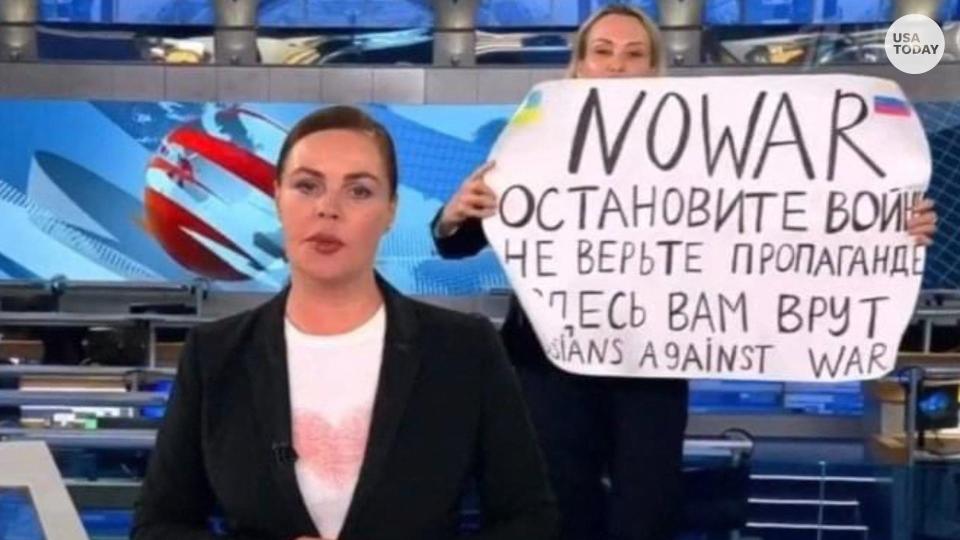

In another open display of dissent, journalist Marina Ovsyannikova crashed Russia’s state news broadcast on March 14 when she burst onto the set holding a giant sign and shouting, “Stop the war” and “No to war!” Ovsyannikova was detained for inciting protests, interrogated for 14 hours and fined 30,000 rubles (about $280).

“There seems to be something of a sea change happening in Russia,” Woolley said. “There are more protests happening right now than there has been in the past during conflicts among Russians. And so giving them access to information is frankly giving them fuel to be able to support democratic engagement and to push back against Vladimir Putin’s autocratic regime.”

How effective those efforts have been is open to debate.

“It’s mixed results, to be honest,” said Soldatov, a watchdog who has been working for two decades to hold Russia’s security services accountable. Russia blocked access to his website, Agentura, on Sunday, but Soldatov said many readers access the site by VPN, so he still has an audience inside the country.

For now, Soldatov said, most Russians appear to be accepting the Kremlin’s version of the war.

But it’s difficult to determine how Russians truly feel about the war and what they believe, particularly amid the crackdown on dissent, because people aren’t eager to respond to surveys and even if they do, they might not be honest, said Anton Shirikov, a researcher at the University of Wisconsin who focuses on propaganda and misinformation.

But Russians tend to embrace anti-West messages, he said.

“There's a centuries-long narrative that Russia was always offended by Europe, that it stood against the world,” Shirikov said. “After the collapse of the Soviet Union, this sort of sentiment became really widespread because people were upset about the loss of the … previous order.”

Because of that, he said, it’s easy for Russians to believe what state-controlled media tells them about the West “being one of the main sources of all our troubles.”

More free VPNs and other tools to circumvent Russian censorship are needed to counter those narratives, Soldatov said. Right now, many of those services require a fee, and the only way to pay for them online is by using a credit card. But Visa and Mastercard have suspended their operations in Russia to protest the war in Ukraine.

More reports by Western journalists covering the war in Ukraine also need to be translated into Russian and distributed in Russia so that people there can see what’s actually happening, Soldatov said.

“If this journalism is available for the Russians, it would be absolutely fantastic,” he said. “That could make a difference.”

Contributing: Anna Nemtsova

PUNISHING PUTIN: Biden announces sanctions on Russia for invading Ukraine. Here's what that means

'WAKEUP CALL FOR AMERICANS': Russia, Ukraine in behind-the-scenes lobbying war over Nord Stream 2

This article originally appeared on USA TODAY: Russia: Schwarzenegger, hackers and more counter propaganda