Pigeon Hills man, 100, survived 39 air missions in WW II. His grandson died in Afghanistan

Quentin Stambaugh thinks it was a Sunday morning in early June 12 years ago that the strange car pulled into the driveway of his ranch home in the Pigeon Hills, just over the hill from where he grew up and has spent all his life.

He saw them pull up, two men in a nondescript car, and he met them in the driveway. It was early, but he is an early riser. He looked at them and they looked at him. He knew why they were there.

“I knew exactly what happened,” he said. “I knew it was bad.”

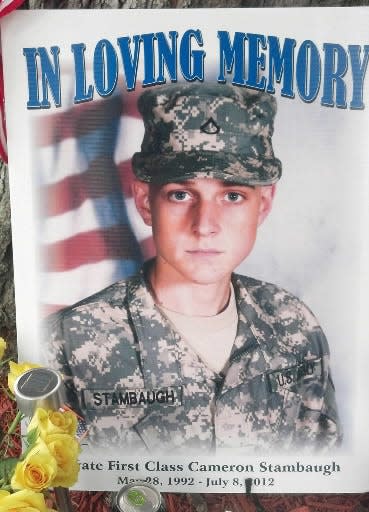

They had bad news – his grandson, Cameron Stambaugh, his hunting and fishing buddy, a young man who idolized him and who had signed up for the military, in part, to honor his service, was dead, killed in Afghanistan. He was one of six members of the 93rd Military Police Battalion killed when an improvised explosive device ripped through their patrol vehicle in Maidan Shahr, a town nestled in the mountains southwest of Kabul.

He slammed his fist on the hood of his pickup truck, leaving a dent.

He reflects on it even now, as he enters his second century on this planet.

He served in the Pacific during World War II, a radioman/gunner on a B-25 low-altitude bomber. He survived 39 combat missions, his aircraft coming under heavy fire as it dropped bombs on Japanese ships from 100 feet or so above the ocean’s surface. On many of those missions, he said, six planes would leave the airbase, and if they were lucky, four would come back. If they weren’t, maybe just two would limp back to base.

He had plenty of opportunities to die – he was lucky to come through the war mostly unscathed – but now he faced it with his grandson’s death.

“I never dwelled on it too much,” he said. “I know you’re always subject to something. I knew you had some rough days.”

He survived war and reached 100 years of life.

His grandson hadn’t, living just a fifth of his grandfather’s longevity, having just 20 years of life.

As he thinks about Cameron, his eyes fill with tears.

It’s hard to talk about, he said.

A good life

Sitting in the dining room of his ranch home overlooking rolling farmland and woods, Quentin recalled his life and how he wound up here, 100 years after his birth. It’s remarkable, and yet, in his telling, it’s not. It’s just a life, and he had to do what he had to do to get here, he said.

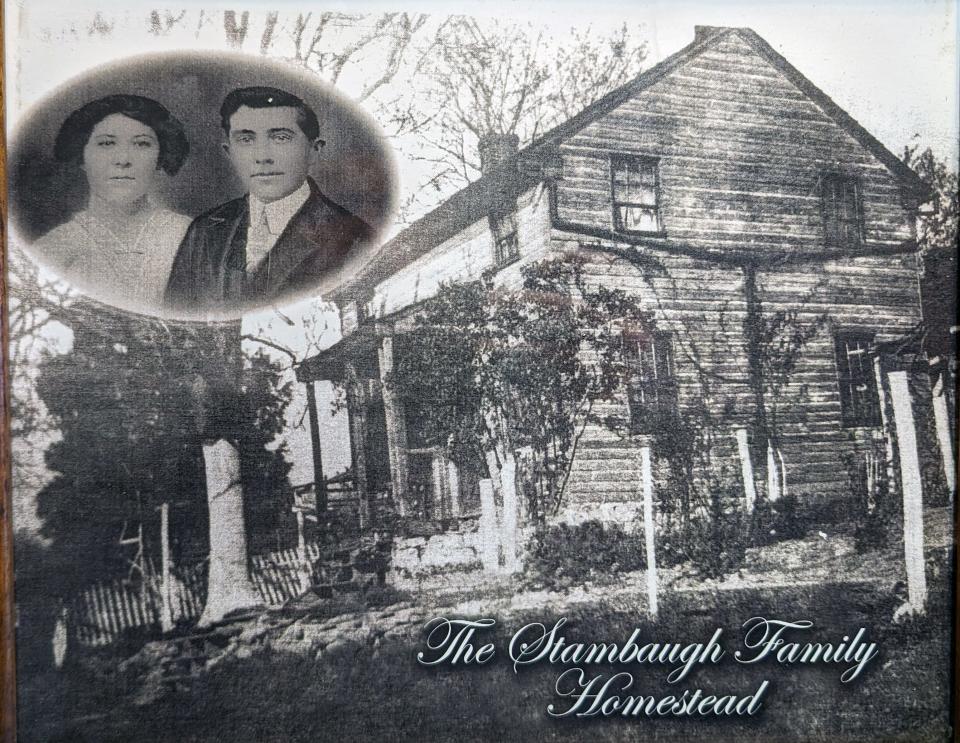

He’s had a good life. He grew up poor, one of eight children raised in a small farmhouse, went off to war, came home and built a life, working at the local paper mill and serving his community as a justice of the peace and district magistrate.

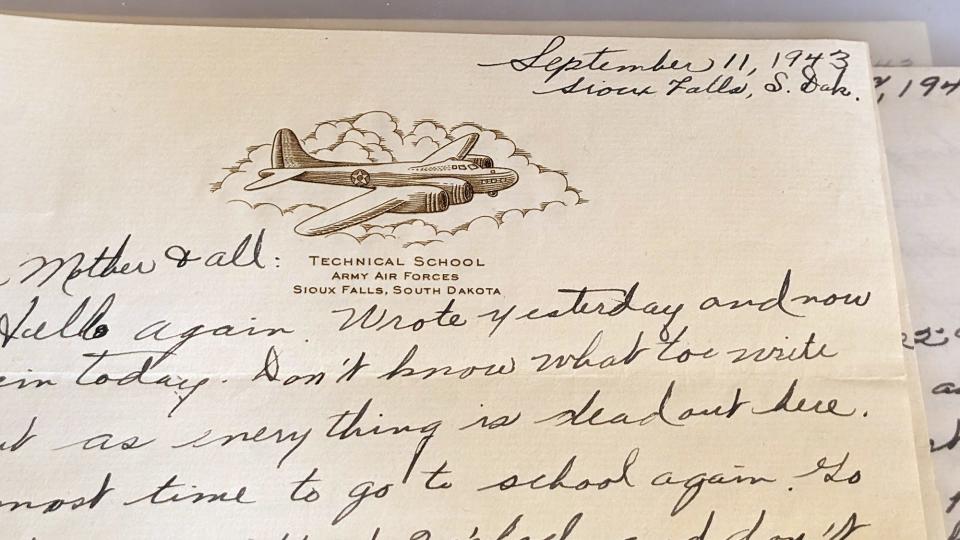

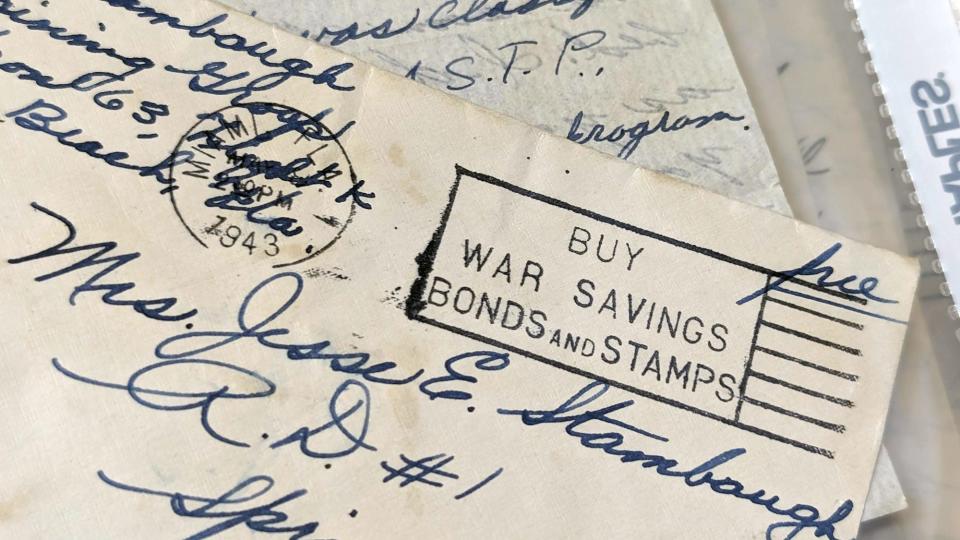

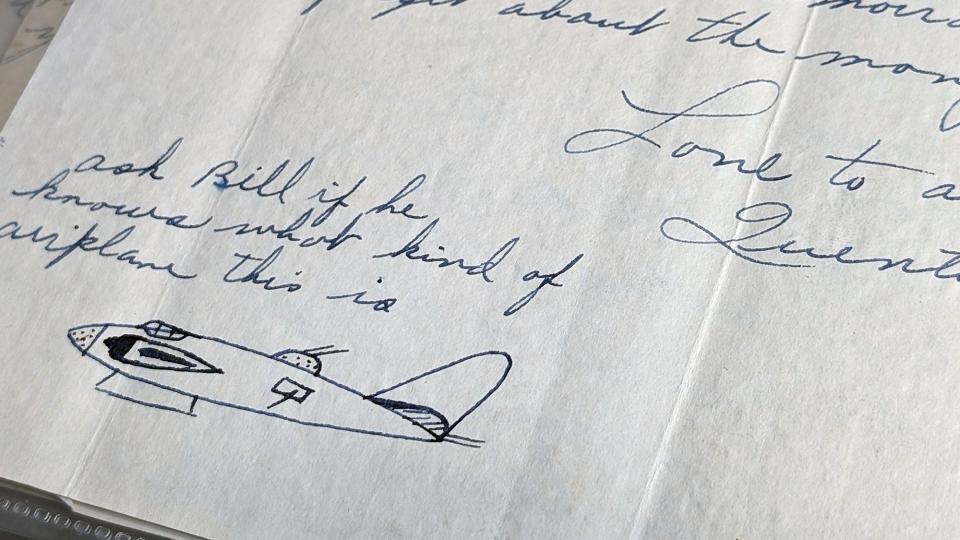

At 100, he doesn’t spend a lot of time looking back. He has a lot of memories, a lot of good ones and some bad ones. His memory is excellent, bolstered by the dozens and dozens of letters he wrote home while in the service. His mother saved all his letters in a large potato chip can; they now reside in two large binders, encased in plastic sleeves.

He has an easy-going manner, and a self-depreciating sense of humor, often downplaying his role in pivotal moments in his life and in history.

He’s still just Quentin Stambaugh from the Pigeon Hills.

'We were poor but didn't know it'

Quentin grew up on eight acres in the Pigeon Hills, west of Spring Grove, one of Jesse and Mabel Stambaugh’s eight children. He was the fifth-born, hence the name Quentin, derived from the Latin root for five.

“We were poor, but we didn’t know it,” Quentin said. “We always had enough to eat. We did what we had to do. We all had chores to do, jobs to do around the house.”

He recalled being sent to a neighboring farm to buy milk with a quarter and returning with a gallon of milk and a penny in change. The family mostly subsisted on what it could grow and kill. Most of the land they owned was covered with woods, leaving about an acre and half to grow corn, wheat and vegetables and raise hogs. They all hunted, plinking rabbits and squirrels with a .22 and hunting deer in the hills. Quentin still recalls his favorite dish, squirrel pot pie. “We didn’t have to buy much,” he said.

Once, he was out hunting, using his brother’s gun. The dog chased a rabbit past him, and he took a shot and missed. The dog chased the rabbit around again, and he took another shot and missed. “I took the gun and wrapped it around a tree,” he recalled. “Broke the stock.”

He went to a one-room schoolhouse – the building still stands, not a stone’s throw from his house, and has been converted into a residence – and in the eighth grade, he transferred to West York High School, a good distance away. Some mornings, he would catch a ride to school with his father, who worked as a construction carpenter. Other mornings, he would hitchhike, leaving home well before dawn and arriving at school “before the janitor,” he said. He wrestled at 90 pounds his senior year.

When he was a kid, he and his friends would ride their bicycles to the Thomasville Airport, watching the airplanes take off and land. Like a lot of kids, he was fascinated by flight. He remembered the plane that would drop mail off at Thomasville flew right over his house. (He still remembers what kind of plane it was – a Stinson Reliant, “single engine, pretty good airplane, made a lot of noise,” he said.)

On one of his visits to the airport, shortly after World War II war began, he overheard the owner, Oscar Hostetter, talking to some other guys, saying, “If I had to go, I’d just as soon fly out than walk out.”

After graduation, he went to work at L.W. Cleaver Auto Parts on West Market Street in York and after a short time, caught on with the Glenn L. Martin Company, building airplanes in Middle River, Maryland.

That’s where he was working when he received his draft notice. He was granted a six-month deferment; the factory was aiding the war effort, building Navy PBYs, a heavily armed flying boat, and his work was necessary to support the war effort.

In March 1943, Quentin’s deferment ran out and he didn’t get an extension. He was drafted and entered the service at Fort Meade in Maryland.

Since he was third in his high school class in typing, he was assigned clerk work at first. But, recalling the words he overheard at the Thomasville Airport, he wanted to serve in the Army Air Corps.

He wanted to fly.

'The best damn place in Pennsylvania'

He went to Miami Beach for basic training, among the inductees housed at the Patrician Hotel, right on the beach. (The Army Air Force took over more than 300 hotels in the tourist destination, attracted by the climate and the flat land. Soldiers trained on the beach and on golf courses, as depicted in photos published in Life magazine.)

During basic training, Quentin earned a marksman badge in short order, scoring 186 out of 200 his first time on the range. The instructor asked him, “Where did you learn to shoot?” Quentin replied, “The Pigeon Hills.” The instructor asked, “What the hell are the Pigeon Hills?” Quentin replied, “Only the best damn place in Pennsylvania.” (He says now, “I was probably lying.”)

He had his bad moments in Miami. Once, while serving guard duty, he dozed off on a stoop as an officer walked by. He tried to make an excuse, something about his shoes becoming untied, but the officer didn’t buy it. His punishment was to clean the floor of the hotel lobby with a toothbrush.

From Miami, Quentin was sent to Yuma, Arizona, for gunnery training, learning to fire a .50-caliber machine gun. The gun was mounted in a turret on the back of a truck, and he was expected to shoot at moving targets as the truck bounced through the desert. “It was like shooting skeet,” he said, “except you’re moving and they’re moving.”

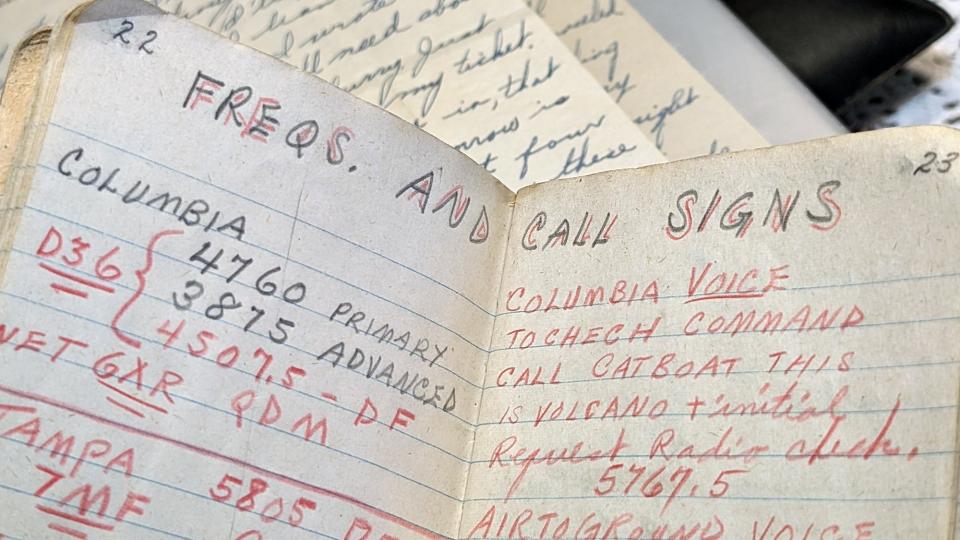

From there, he went to radio school in Sioux Falls, South Dakota. He learned Morse code – “Everything was code,” he said – and everything about radios, taking one apart and rebuilding it and repairing it when it broke.

While in Sioux Falls, he had a chance to do some pheasant hunting. One day, he said, he was hitchhiking off the base to do some hunting, his .20-gauge shotgun slung over his shoulder, when two men in a Cadillac stopped to give him a ride. They got to talking and it turned out the men were from York, vacationing in South Dakota. It was among the numerous times he ran into people from his hometown while serving hundreds of miles away from home. In Miami, one of his fellow inductees was from Stoverstown, not far from his hometown. Later, he would encounter soldiers from York County in far-flung places.

From Sioux Falls, he was sent to Columbia, South Carolina, where he was assigned to a B-25 crew. The crew trained together and during one training mission, Quentin recalled, the pilot was cruising at 7,000 or 8,000 feet or so when he went into a power dive. Quentin recalled being pinned to his seat; he couldn’t even lift his hand to tap on the Morse code key. The pilot pulled out of the dive, but it was too late. The plane’s landing gear clipped a dance hall.

He was assigned to the 498th Squadron of the 345th Bomb Group and shipped out to the Pacific, but Quentin, at some point, was left behind, hospitalized with strep throat, an infection that had plagued him in his youth. He flew out after the crew, heading from South Carolina to Sacramento and then to the Philippines. As they headed to the war, he recalled, the pilot flew through San Francisco and guided the plane under the Golden Gate Bridge. “I don’t think he was allowed to do that,” he said.

When he landed in the Philippines, his crew had moved on. He tried to catch up with them but couldn’t. He kept in touch, writing letters to a crewmate named Canterbury, a turret gunner, pledging to rejoin the crew.

Meanwhile, he was in a transit camp, adrift. A commanding officer learned that he could type and commandeered him to be his secretary/valet/servant. He typed reports and made sure the officer’s glass was always full of whiskey. It wasn’t what he signed up for.

Soon, he was back on the flight line, serving as a radioman/gunner with any crew that needed one. His new crewmates never said what happened to the old radioman/gunner.

At about that time, he received a reply from Canterbury, sort of. One of his letters to his former crewmate was returned stamped deceased. “It sure isn't pleasant news, but this is war,” he wrote his mother. “Let’s hope it’s over soon.”

Later, he learned that every member of the crew died in a bombing mission. The crew’s B-25 was shot up near Formosa. (Formosa is now Taiwan.) The pilot augured the plane into the bridge of a Japanese destroyer, sinking the ship. They were "truly heroes, all of them,” he wrote to his mother.

He flew 39 missions. His squadron was assigned to attacking Japanese warships in an effort to disrupt supply lines. Frequently, these were high-risk missions. The pilot would bring the B-25 to the deck, flying low and at the last second pulling up to drop the plane’s bombs on the enemy ship. The squadron attracted a lot of gunfire and “ack-ack” shrapnel. He returned from a lot of missions with the plane Swiss-cheesed with holes from flak and gunfire.

On one mission, he said, his crew was tasked with finding out whether there were any survivors of another aircraft that had been shot down. They spotted a survivor on a raft bobbing in the ocean and a Navy PBY – the same plane he helped build as a civilian – came in and rescued the man. It turned out that the survivor, who had been in the water for about five days, was from York, a guy named Burhans – William “Shorty” Burhans. Quentin wrote home after the rescue and told his mother that Burhans had lived with his wife on North West Street in York, suggesting she visit. “I don’t know where that is,” he wrote. “Maybe you have a better idea.”

Another mission took too long to complete – “We were way overdue,” he said – and on the way back to base, as his plane was approaching Subic Bay, it was running out of fuel. The pilot instructed the crew to jettison anything that was not necessary − to lighten the load. Quentin threw the waist guns out, smashing the Plexiglas canopies, belts of ammunition and whatever he could find to reduce the plane’s weight. They made it back, just barely, he said.

He has a photograph taken by the tail camera in the plane, designed to record its missions, that shows a Japanese destroyer listing on its side as sailors bail into the sea, looking like ants streaming down the side of the massive ship. The camera took a photo every ten seconds. He said the next frame would have shown the results of him raining .50-caliber rounds on the survivors.

“We never had a milk run,” he said. “Every mission had a lot of stress to it. I think stress would be the word. We lost a lot of planes. We’d always had a debriefing when we got back. Some didn’t get back.”

Don't fly through the cloud

Among his last missions was serving as patrol for a plane on a secret mission. It was Aug. 6, 1945. The plane they were protecting was called the Enola Gay.

He recalled seeing the mushroom cloud over Hiroshima. The crew was told not to fly through the cloud.

His last mission

Quentin vividly recalls his last mission.

His plane flew in tandem with another B-25. The two planes were supposed to fly together, to provide cover for one another. The pilot of the other plane, he said, didn’t have a lot of experience; it was his first bombing mission in which a ship was targeted.

“We lagged behind,” he said. “The other plane got way ahead of us and dropped its bombs 50 or 100 feet short of the ship.”

The bombs exploded under Quentin’s plane. A geyser of seawater gushed through the open bomb bay doors, flooding the cabin and slamming Quentin into the Plexiglas canopy of his turret. The impact forced his helmet down over his face, slicing open a gash on the left side of his nose.

He reached for the junction box to let the rest of the crew know he was injured, but otherwise all right, but it had been blown away. The plane was full of holes, he recalled.

As they banked away from the target, and climbed to 4,000 feet or so, Quentin said, they were jumped by two Japanese fighters. They dove to right above the water and tried to shake the fighters. After 20 or 30 minutes, he said, they had escaped.

When he returned, medics closed up the laceration on his face with butterfly bandages. As was custom, he went to the squadron’s clerk and asked for whiskey, a double shot to celebrate his return. The clerk, seeing the slice on his face, handed him two half-full bottles, which he took back to his tent and consumed with some crewmates in short order. He then passed out on his bunk.

Not long after, he was informed he had accrued enough points to go home; you needed 100 and he had 103.

He spent the next day on the beach, looking for seashells. He had taken his air mattress to the beach and dozed off on it. He awoke on the ocean, the tide had washed him out to sea. He could see the top of the volcano that formed the island and began paddling. It took him two hours to return to shore.

He did some fishing and boar hunting. He recalled dynamite fishing, tossing charges into a lagoon and waiting for the fish to surface. The natives, he said, declined to wade into the water to retrieve the fish, fearing the crocodiles that resided there. He and the guys with him loaded up their M-1 rifles and said, “You get the fish. We’ll get the crocodiles.”

He then started looking for a way to get off the island and find a ride home.

Another WW II story: York WW II veteran and POW, 100, shares harrowing tale of being shot down over Germany

Quentin's grandson's story: Spring Grove father mourns son, a 'noble warrior'

Life after the war

Quentin caught a ride with an Australian PT tender heading for San Francisco, dodging typhoons on the way home. Two of the ship’s three engines failed and it limped into harbor, overdue. He boarded a train for Baltimore, and then on to York. His brother picked him up at the train station on a Saturday afternoon. First thing Quentin wanted to do was get to Zeigler’s Hardware before it closed so he could get his hunting license and go hunting Monday morning. He left the service with the rank of Tech Sergeant.

He met his wife, Bertha “Sis” Holtzapple, at the 10 Mile House, a beer hall on Route 30 near the Pigeon Hills. He remembered her from high school; she was a year behind him at West York. “We just started chatting and one thing led to another,” he said. They wed in 1947.

He was trying to figure out what to do with his life and enrolled at Franklin & Marshall College on the GI Bill. “I had no business being there,” he said. “I did a year and a half.”

He got a job at P.H. Glatfelter, the paper mill in Spring Grove. He and Bertha raised three children, Bonnie, Jeffrey and Mitchell. He had six grandchildren and six great-grandchildren, including a set of twins. Later, he served as justice of the peace and district magistrate in Spring Grove for 37 years. He retired when he turned 80.

Two of his grandchildren passed before him. Jeffrey’s daughter, Gina Stambaugh, was killed in a car crash in 1993.

And Mitchell’s son, Cameron, died in Afghanistan in 2012.

They call him a cat

His friends call him a cat, since he seems to have had nine lives. He had some close calls in the service − and one after. He was changing the oil in his car – he was in his 60s at the time – jacking the car up with a bumper jack when the jack went sideways, and the car fell on him. He yelled, his words indecipherable, and his wife, in the house, thought that maybe the cat got hit by a car.

A neighbor came over and found him, pinned under the car, unable to speak. The neighbor jacked the car up and dragged him out from under it. He had five broken ribs, two torn loose from his sternum. He laughs about it now. He made it through the war, with people shooting at him with ill intent, and “I got messed up in my yard,” he said.

'We just did what we had to do'

Quentin and Cameron were buddies. Cameron always looked up to his grandfather.

“He was my hunting buddy,” Quentin said. “His hearing was a lot better than mine, so he was my ears in the woods. He’d say, ‘Grandpa, I hear a deer. I hear a deer.’ I couldn’t hear shit. And then, a deer would walk right in front of us.”

He recalled spending days fishing with Cameron, going for trout in the streams around southwest York County or fishing for bass, just hanging out and talking.

He said, “Those are the kinds of things I think of.”

His grandson was doing what he had to do when he met his end on that dusty road in Afghanistan. Quentin understands that.

“We just did what we had to do,” he said. “Some of us came home. Some of us didn’t.”

Columnist/reporter Mike Argento has been a York Daily Record staffer since 1982. Reach him at mike@ydr.com.

This article originally appeared on York Daily Record: Pigeon Hills PA man, 100, survived 39 Pacific air missions in WW II