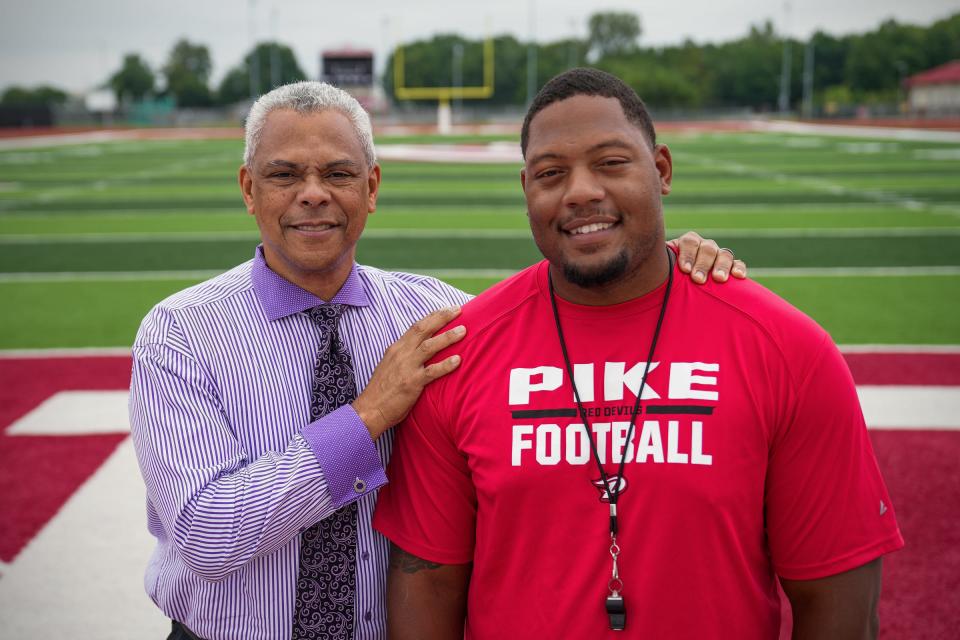

Pike coach Mike Brevard was homeless but never alone. 'All he needed is that chance.'

Long before Michael Brevard was a coach, he was a kid with a dream. So close, he could almost reach out and touch it from the family shelter where he stayed with his mother, Wiloner.

“From my window, I could see Lucas Oil Stadium,” Brevard said. “My senior year at Ben Davis, we played a primetime game on a Saturday at Lucas Oil Stadium against Warren Central. I remember taking it all in like, ‘I used to live right by this stadium.”

Brevard, 30, does not shy away from sharing his journey. He did back then, though. As a 16-year-old at Ben Davis, nobody knew he caught two city buses to get to school. He never mentioned he had lived in a shelter in Richmond, Va., where he would sleep on a cot, wake up and go to school, hang out at the public library after school until his mom met him and his brother, then walk back to the shelter and do it all over again the next day. He never told anyone he was homeless.

What we learned in Week 2:Surprises, hot takes, Purdue gobbling up Indy recruits

Brevard, Pike’s first-year football coach, did not feel it necessary to share those experiences then. But he watched, learned and asked plenty of questions. And now, when one of his players comes to him with a predicament over one of life’s curveballs, he can offer first-hand experience.

“Some of these kids are like, ‘I come from the trenches,’” Brevard said. “I came from the trenches. I came from the bottom. A lot of people don’t believe that because of the way I speak now, but it wasn’t this way in 2008.”

Brevard did not do it alone. His mother, an Army veteran with more than 17 years of service, chose family shelters for Mike and his older brother, Julius, over worse alternatives. “Her biggest fear was us turning to the streets and not having any guidance,” Brevard said. By fourth grade, two years after moving to Richmond, Va, from Minnesota, then Tennessee, he felt stable. They were out of the family shelters and Mike was thriving in school. “Life was definitely going in the right direction.”

A family connection and football led Wiloner and Michael to Indianapolis in 2008, a move that looked perilous when Wiloner’s brother was incarcerated, and they found themselves living in a family shelter again. But it was also when Michael met the man he calls his “spiritual father” — a connection that has only become stronger over 14 years of long talks, shared tears and many laughs.

***

Dennis Goins jokes his initial connection to Brevard was more of a coincidence than divine intervention. Goins, who had gotten out of coaching at the time, was several years into his role as the director of Ben Davis Television, a program he developed after his 20 years as an award-winning photojournalist in the television industry.

“It seemed like he was always stopping by my class,” Goins said of the then-recently enrolled Brevard. “I thought, ‘Well, maybe he’s coming by to see me.’ But I think he wanted to see a couple of other people in my class.”

Whatever the reason for his frequent visits, Brevard and Goins quickly developed a connection. Goins was a former star basketball player in Rushville who played in college at Vincennes University and Southern Illinois before graduating from Ball State.

“The Lord provided me with another outlet to coaching,” Goins said. “It was Mike.”

Goins and his wife, Desiree, were struck by Brevard’s story, but also his low-key and inquisitive personality. “An old soul,” Goins called him. A lot of that came from his mother, Wiloner. She did not tolerate ‘C’s’ on Michael’s report cards and always encouraged both of her sons to ask questions, be humble and “to learn how to say thank you.”

“We often hear, but we don’t listen,” Goins said. “(Mike) will ask you 1,000 questions. My wife and I always talk about that. He’ll always ask questions. ‘Should I pay for a dryer with cash or a credit card?’ Those are questions some people wouldn’t even consider asking. Mike’s a thinker.”

Brevard quickly became part of the Goins’ family. Dennis and Desiree have two children of their own, daughter Jordyn and son Benjamin, and it was not the first or last time they had connected to a student in need. Goins came from a family of nine and his home in Rushville was always full of brothers, sisters, aunts, uncles and cousins.

“Usually I gravitate toward knuckleheads,” said Goins, who has been teaching at Ben Davis for 20 years. “But Mike wasn’t the knucklehead. He never came off to me as being one of those kids who needed much but love — unconditional love. … The remarkable thing is Mike was homeless and no one knew. He never let that stop him from doing anything he wanted to accomplish.”

He might have been homeless at times, but never alone. His brother, Julius, is six years older and moved to Minnesota before Wiloner and Michael came to Indianapolis. Wiloner and Michael again lived in a family shelter for several months after Wiloner’s brother was incarcerated, but it never felt like a hopeless situation to Michael.

“First off, I’d say kudos to my mom,” he said. “People think ‘homeless’ you are living on the street or something like that. My mom chose to go to family shelters to get us out of bad situations.”

But Wiloner knew Michael, especially at the influential age of 16, needed a male figure in his life. “Michael didn’t have a father figure,” Wiloner said. “Mr. Goins was a great influence as a mentor. I was a single parent and raised Michael and his brother, but even today I tell Dennis ‘thank you’ for being a man who was a positive role model in his life.”

Brevard, a 5-11, 220-pound linebacker, made 51 tackles as a senior on the 2009 Ben Davis football team. He embraced his role on the football team and enjoyed his time at Ben Davis, in large part due to his relationship with Goins, who encouraged Brevard to attend church with him.

It was, at first a turnoff to Brevard, who was skeptical of adults talking about God.

“People would speak about God, but they weren’t about God,” he said. “One thing Mr. Goins told me was, ‘If you believe in God, I should see God in your actions.’ I think about that as coach. I have to be who I am. I can’t say I’m a believer and then be out there M’fing the kids. That’s not who I am.”

Spirituality was a topic of conversation, but the connection between Goins and Brevard was not always serious. Brevard laughs now about a story Goins told him about how his wife would squash fresh berries every morning and put them in his hair. Goins could hardly keep a straight face when the ever-inquisitive Michael asked her about the morning routine.

“He asked my wife, ‘Is it true?’” Goins said with a laugh. “She just looked at him.”

It is those moments and memories that connect them to this day, but it is also an ever-evolving relationship. When Michael went to St. Francis in Fort Wayne to play college football, he suffered a serious neck injury during a game at Lindenwood University his freshman year. He was taken off the field on a stretcher unable to move his hands or feet. He eventually got feeling back, but needed cervical spinal fusion, surgery that would keep him off the field for a year.

When he awoke from surgery, Goins was there.

“Mr. Goins, my linebacker coach, Joey Didier, and the doctor were praying over me,” Brevard said.

Brevard took a year off from playing, but it was that year as a student coach that made him want to get into coaching. He finished out his three years playing football at St. Francis before starting out as an assistant at Fort Wayne Northrop for a year, then working as the defensive coordinator at Fort Wayne Wayne.

A year later, at 25, he was named Fort Wayne North Side’s coach. The results on the scoreboard were not good. North Side finished 0-10. At the end of the last game, a 14-6 sectional loss to Elkhart Memorial, Brevard walked on the track toward Goins.

“I felt like the worst coach in the world,” he said. “I wanted to resign. When I saw him on the track, I just collapsed and started crying. He said, ‘Congrats son, you’ll never go 0-10 again.’”

Brevard led North Side to steady improvement, from 0-10 to 2-8 to 4-6 to 5-6. When an opportunity to coach as an assistant at St. Francis came about in 2021, he jumped on it. His goal, originally, was to coach in college. But when the Pike job came open, Goins encouraged him to apply.

“I bleed purple, but I’m a 33-year resident of Pike,” Goins said. “I’m so happy Mike got this job and took advantage of this opportunity. He wasn’t sure. It took him a while to make that decision because he’s a thinker and a listener. He didn’t want to put his family in jeopardy in any way. But now that he’s here, he’s going to turn this place around. He’s going to change the culture because of the experiences he’s had and this community is going to love him. All he needed is that chance.”

***

Brevard and his wife, Abbe, are parents to 6-year-old son Marshall, and 2-year-old daughter Avi. When the Pike job came open, Mike was interested, but immediately started going through all of the other things — his wife’s job, his kids’ school, selling the house — that would be impacted by the move.

“My dream is them,” Brevard said of his family.

But with Abbe’s blessing and encouragement, Brevard applied. Goins played a big role, too, ensuring him he would be a good fit at Pike. “Everything fell into position,” Brevard said. “I went through months of worrying, but I think we’re in a better position now than I thought we would be at this point.”

Pike struggled to 1-9 seasons in 2018, 2019 and 2021 and has posted just two winning seasons since joining the Metropolitan Interscholastic Conference in 2013. The Red Devils nearly won the opener against Zionsville, falling 31-24 in double overtime and led Fishers 17-7 last week before eventually falling 28-17.

Among those in the crowd vs. Zionsville was Michael’s mother, Wiloner, who lives in an apartment near Ben Davis.

“I thought it was outstanding,” Wiloner said. “I was on the edge of my seat. I wanted my baby to win that first game. I’m very, very proud of him. I tell Michael all the time — both my sons — how proud I am of them. Neither one has been in jail or into drugs. One of the things I always told Michael was getting an education can take you farther than not being educated.”

Michael’s first call after the game was to Goins, who was not able to be there due to his job — working at the Brownsburg-Ben Davis game several miles away. It was his first call when he found out Abbe was pregnant with Marshall. It will be his first call again.

“Everything my mom preached has come true,” Brevard said. “Everything Mr. Goins preached has come true. He has a phrase, ‘You laugh now, but can you laugh later?’ Because Mr. Goins is a positive guy and always spreading the word, sometimes kids can look at a guy like Mr. Goins and say, ‘Oh he’s supposed to say that. He’s just old.’ But there’s a lot of truth to it. I use the same phrases now. It’s funny how life comes full circle.”

Call Star reporter Kyle Neddenriep at (317) 444-6649.

This article originally appeared on Indianapolis Star: IHSAA football: Pike coach Mike Brevard motivated by homeless past