Pioneer who was among first Latina women to work in Arizona government turns 100

Marguerite Trujillo didn't envision herself as a pioneer when she began working an office job in Phoenix in the late 1930s, when those options were typically closed to women. But she grew into a rising star for the Latino community in Arizona when she landed a job in Washington, D.C., advocating for herself and other Latinos along the way. For Trujillo, it was a matter of doing what she thought was right.

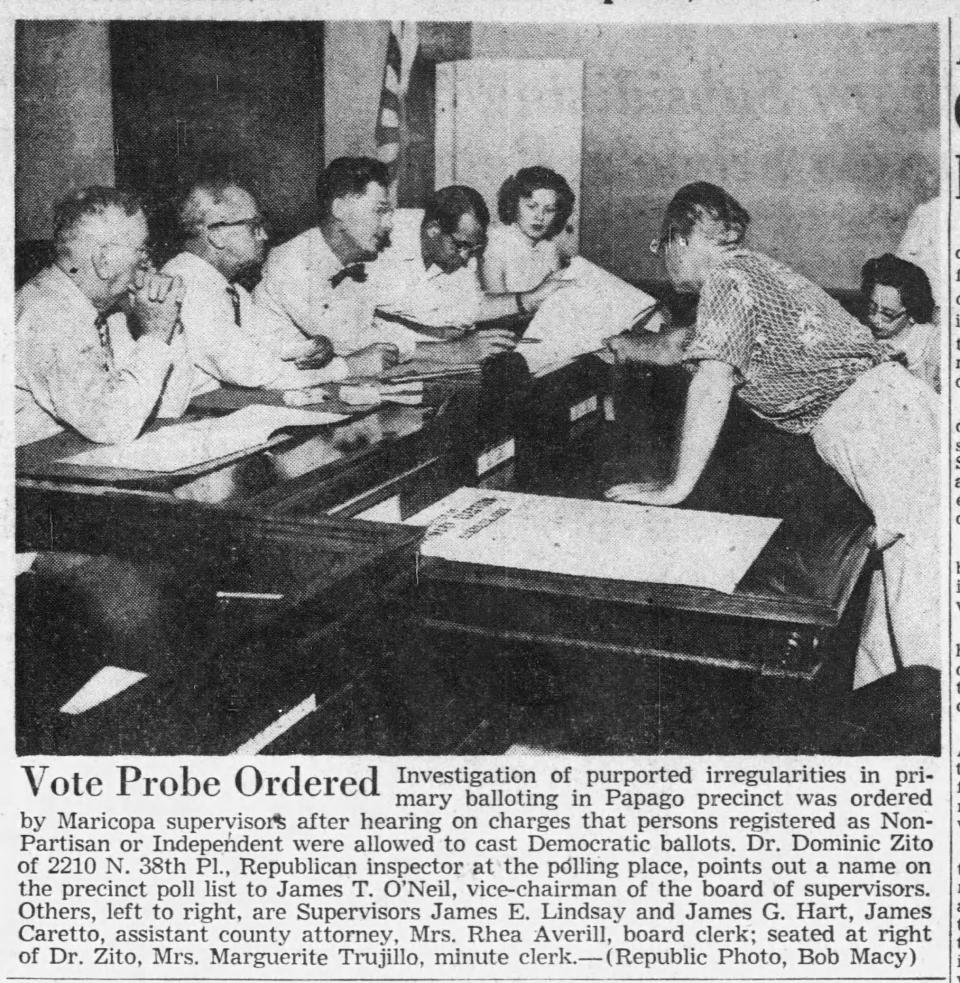

Now, at the age of 100, the impact of her long career behind the scenes in city and state government as one of the first Latinas to ever walk that path remains.

She lived through meat-rationing in the darkest days of World War II, when those without a ticket could only get horse meat. She participated in the effort to eradicate tuberculosis. And she witnessed what she calls a shift in dynamics in Washington, which was a neighborly second home for politicians when she lived there.

“A lot of interesting things happen when you turn 100,” Trujillo said, noting that she’s still writing thank-you cards to those who reached out for her birthday, April 22.

She always found a way to get involved in whatever she was doing at a given time, Trujillo said. She was instrumental in moving the clerical work at the state Legislature over to computers in the 80s, supported public health initiatives and charitable efforts benefitting Latino youth and founded a group of her own for women.

Even at the century mark, she’s never stopped helping her community, said Anita Luera, Trujillo's goddaughter.

“When she retired, she didn’t really retire,” Luera said. “She always found something. She’s always been helpful.”

Making a home in Washington, D.C.

Trujillo worked at historic Phoenix diamond company The Boston Store just before the start of World War II. She was the only Latina working in an office in Phoenix.

Two rival Spanish-language newspapermen, Pedro de la Lama and Jesus Franco, were friends with her mother and knew about Trujillo. They both suggested her to U.S. Rep. Richard Harless in 1944 when he was looking for an administrative assistant.

The Arizona congressman's former administrative assistant was a Latino man from Tucson. He wanted someone with a similar experience and cultural background who could join him in Washington.

“I think that was all the congressman needed, because these two political rivals submitted the same name,” Trujillo said.

It was difficult to get a plane ticket at the time, so Trujillo took the bus to D.C. alone.

“It was scary because I didn’t know anyone and, frankly, I didn’t know where it was,” Trujillo said. “I knew it on the map, but not how far away it was. It took forever. I think when I got there, I slept for two days.”

She couldn’t tell her mother that she was leaving because her mother was in Nogales, Arizona. Trujillo sent her a telegram from Washington when she arrived.

“She had no idea I’d moved. She thought I went to Washington state,” Trujillo said.

While she was there, she befriended employees of Latin American embassies as well as her neighbors, a congressman from New Mexico and a territorial representative from Puerto Rico. When she moved farther away from downtown, she hitched rides with people on their way to their offices. They put cardboard signs in their windows indicating where they were headed, and she jumped in to a car going to her destination.

“Everybody was really friendly,” Trujillo said.

A star at home and in Washington, D.C.

Trujillo become an unwitting local hero in the Latino community in Phoenix when she landed her job with Harless.

The congressman often joked she was more well-known than he was because the Spanish-language newspapers used her photo whenever they printed an article about him. At the time, she didn’t like the attention.

“I was so embarrassed,” Trujillo said with a laugh. “I never read the stories. I never translated the stories for the office either. I just hid them.”

When her mother died, she found a box full of those old newspapers and decided to save them.

Trujillo was invited as a guest to two State of the Union addresses and a former colleague booked her a suite in a hotel for a conference on polio after her tenure in Washington. Her first and favorite State of the Union Address was President Franklin Delano Roosevelt’s final address, where she got to sit in the presidential box.

“The whole thing gave you goosebumps,” Trujillo said. “Some people couldn’t even get standing-room only, and I come into town and get into the presidential box. And I was working for a Democrat and invited by the minority-leader Republican.”

By the time she returned from Washington, the social climate in Arizona was different. More Latinos began working office jobs. Though she was friendly with many people, she still sometimes fielded comments about her identity from colleagues who would say she didn’t look or sound Mexican.

She usually responded with a joke that she left her huaraches and zarape at home.

“I had several incidents like that,” Trujillo said. “And I handled them that way because it was obvious people didn’t realize what they were saying or who they were talking to.”

A ‘how do we solve this?’ kind of thing

When Trujillo went to work for Harless, there weren’t many opportunities for women aside from social worker, teacher or nurse, she said.

She didn’t want to be a nurse because she couldn’t imagine herself then caring for sick people. She didn’t want to be a teacher because she didn’t want to be surrounded by children. She didn’t want to be a social worker because she didn’t have the patience she does now.

“I would help anyone who asked, but if you came back to me with the same doggone problem, I couldn’t stand it,” Trujillo said. “So instead I decided to become a secretary and tell the bosses what to do.”

When Trujillo ended her stint in Washington, she started working for the Arizona Corporation Commission, but the agency only budgeted to pay one person to take notes on the Legislature, so she was being underpaid. She decided she could no longer stay in that role.

“I said, ‘I’m doing this work, I have the experience, and I think my wages should reflect that,’” Trujillo said. “I told them when they got more money next session to let me know, and I’d transcribe the minutes in my notes, but I was done. I left and went to work for the Arizona Brewing Company.”

She later went on to work for the Arizona Superior Court as a bailiff, a court reporter for the city of Mesa and, shortly after her retirement in 1986, took a job with the Arizona Legislature as an assistant to Rep. Earl Wilcox.

For more stories that matter, subscribe to azcentral.com.

It helped that her husband was supportive, she said. Not only did he encourage her to continue working, but he got their children ready for school and fed them breakfast. He died in 1983 at the age of 64 as a result of battling kidney problems after he came down with malaria six times when he was deployed as a National Guardsman.

She and her husband belonged to Latino organizations such as the Vesta Club and Friendly House. Trujillo also helped established Las Damas del Valle, a network of women serving the Latino community that does everything from donate to Boy Scout troops to public health campaigns.

Even now, Trujillo helped the elderly access the COVID-19 vaccine, reminiscent of her efforts to get people immunized when the polio vaccine came out.

“When people started rolling out the vaccine, she called me and said, ‘We have to do something,’” Luera said. “She was calling me, she called city hall. She’s always had a ‘How do we solve this?’ kind of thing.”

Megan Taros covers south Phoenix for The Arizona Republic. Have a tip? Reach her at mtaros@gannett.com or on Twitter @megataros. Her coverage is supported by Report for America and a grant from the Vitalyst Health Foundation.

This story is part of the Faces of Arizona series. Have feedback or ideas on who we should cover? Send them to editor Kaila White at kaila.white@arizonarepublic.com.

Support local journalism. Subscribe to azcentral.com today.

This article originally appeared on Arizona Republic: Marguerite Trujillo, former Rep. Richard Harless' assistant, turns 100