Placer County homeless quietly move into suburban homes. How unusual program is working

Yankee Hill Estates in Rocklin is described by its residents as peaceful and welcoming — a slice of Placer County with moderately large homes, lawns to mow and a park for the kids.

But right in the middle, there is something you might not expect: a six-bedroom house where formerly homeless men and women live. It looks like every other house on the block except for this striking difference.

It’s part of a network of houses for the homeless and mentally ill funded by millions of dollars from Placer County and run by two non-profit organizations, The Gathering Inn and Advocates for Mentally Ill Housing.

As cities around the country struggle with a growing homeless population and few solutions beyond temporary homeless shelters or single-occupancy hotels, Placer County has been placing some of its homeless population on quiet suburban streets.

It’s an attempt to fully integrate formerly homeless people into the community without the extreme costs of building permanent affordable housing.

To some, the introduction of homeless people came as a shock. Many in the Rocklin neighborhood were caught off guard and said they didn’t discover the arrangement until February when new residents began to move in.

In interviews with The Bee, neighbors also said the existence of the home could threaten their property values, and that erratic behavior, loitering, drinking and smoking in public are unwelcome in their neighborhood.

But for the formerly homeless people who occupy the homes, they’ve found a new sense of comfort without the hassles of living in shelters, on church doorsteps, or the street.

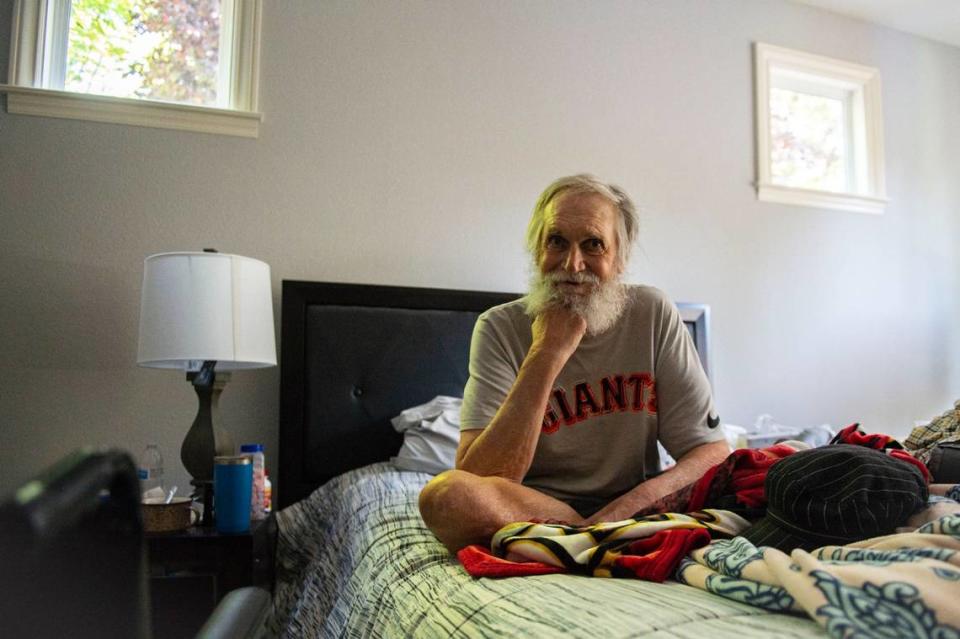

“It’s very very nice. In fact, it is the nicest place I’ve been in,” said Robert Borden, a resident of the home in Yankee Hill Estates. Borden, who says he’s been homeless for years and is bound to a wheelchair, lives in a downstairs bedroom, which he says is the ideal set up for him.

“I’ve been in plenty of places and I went back outdoors. I’ve been to ones in West Sacramento. I’ve been in some in Sacramento. And this by far beats them all,” said Borden, who says he pays 40% of his $1,000 Social Security check toward rent each month.

“We have our own freedom. If you toe the line and follow the rules there’s never any problems,” he said. “Everyone gets along. There is no arguing. It’s almost better than your own home.”

The unique arrangement in Placer County contrasts starkly with the extraordinary per-person costs of developing new housing for homeless people in California. At the Capitol Park Hotel downtown, for example, development costs will reach more than $445,000 per unit for apartments that are tiny — about 250 square feet.

With the program in Placer County, six people live in each of the four houses — purchased for about $600,000 each — a significantly lower per-person cost than new affordable housing developments. In total, the single-family homes provide space for about 24 people, still only a fraction of the homeless population in the county.

The project is launching as the homeless population continues to rise in Placer County, a mix of suburban and rural neighborhoods where the median household income is more than $85,000. A “point-in-time” headcount this year found 744 homeless individuals in the county, while 617 were counted in 2019 and 584 in 2018.

Both AMI Housing and The Gathering Inn each received a little more than $2 million from Placer County to own and operate homes through 2022. The contracts provide each with $1.5 million to purchase homes, and $500,000 for operational expenses.

The Gathering Inn purchased the home in Rocklin in January and another six-bedroom home in Lincoln in March, both with all cash. AMI Housing, the group that works primarily with the mentally ill, purchased two homes for about the same prices in all-cash in Rocklin and Auburn in December 2019. The homes are exempt from property taxes because of their use.

“We are continuing to move aggressively to purchase more housing and make a dent in our homeless population,” said Jeff Brown, Placer County’s director of the Health and Human Services, when the program was announced last October. “This effort will not only help the most vulnerable among our homeless population get housed, but will also make sure they receive ongoing support so they can thrive.”

The houses allow all genders to live in the homes, but not children. The residents are screened and referred to the homes by Placer County’s Whole Person Care, a five-year, $20 million program designed for people who are frequent users of public services such as emergency rooms, jails, mental health, substance use programs and social services. Registered sex offenders are not allowed in the homes, but those with a criminal history are, including felons.

“The idea is to continue to build and eventually get these folks into something that’s more independent,” said Nick Golling, a program director for The Gathering Inn, “so that we free up space in these permanent supportive houses for the next folks that are going to come in.”

‘I’m having to get security systems now’

As with nearly every effort to introduce homeless housing or shelters into neighborhoods, the homes in Placer County have alarmed some neighbors, while others have accepted the new residents with a shrug and few complaints.

The Sacramento Bee spoke with more than a dozen neighbors, many of whom were upset they were not notified by the county beforehand.

Residents expressed frustration that under current law, a nonprofit like The Gathering Inn can purchase a single-family home and not disclose its intended use before people started moving in. But when they want to sell their home, the rules of their homeowner’s association require they must disclose “noise, nuisance or other problems” to potential buyers, something they see as a double standard.

Some were confused about the exact purpose of the houses, calling them halfway houses, and worried about living near people with criminal backgrounds or who abuse drugs.

Most neighbors critical of the program declined to be quoted using their names, fearing public or social media backlash. One neighbor echoed what every other neighbor interviewed by The Bee said: Placer County did not have “any information disclosure, door-knocking, introduction, town hall meeting, letter via mail or in-person to disclose what the plan was for this property.”

Chris McElvain, a neighbor to one of the homes in Lincoln owned by The Gathering Inn, believes his home has dropped in value because of the homeless housing. McElvain said he didn’t have any problem with the house, but like others thinks the county had an obligation to notify neighborhood residents.

“I have compassion for these people, but I should have been notified,” he said. “There should have been a vote at city council. The county never told anybody that this was happening.”

McElvain, a Navy veteran who served in Afghanistan and Iraq, grew up in a low-income area of San Jose. He said he has compassion for the residents because each of his brothers was homeless at one point.

McElvain purchased his home in 2010 to build up equity to help his children afford college. He said he planned to sell in a few years to access that equity, but now is uncertain of that plan. At the time of the Bee’s interview at his home, McElvain was spending as much as $100,000 renovating the house and employing an additional worker.

“You see, I’m putting money into this house,” he said.

At Yankee Hill Estates in Rocklin, residents with young families seemed particularly upset about the arrangement.

“They smoke weed every day. Now my kids know what that smells like,” one neighbor told The Bee. This neighbor said they complained to The Gathering Inn program manager and were told that marijuana is legal.

Neighbors also described an incident where “a guy with a knife or machete was hitting on a tree,” outside of the home.

“I’m having to get security systems now,” another resident said.

However, police service call records show there has been one call for service, in April, “for verbal disturbance” to the Yankee Hill Estate home since it was acquired in January by The Gathering Inn.

In conservative Placer County, the concern over safety for many residents with young children intersected with politics. Residents said the county could use the money more “strategically” and complained that people who “made all the wrong choices” end up living in the same neighborhoods with hard-working people.

“That’s not fair,” one neighbor said. “Do we just keep coddling them in fancy neighborhoods?”

Bob Mauer, a neighbor to the new The Gathering Inn home in Lincoln, was disappointed to learn of the home’s intended purpose. “I think it is a very poor use of taxpayer funds,” he said.

The Sacramento Bee was originally alerted to the existence of the homes by a neighbor, Natalie Grand, who complained of misdeeds by the county, The Gathering Inn and home’s residents to The Bee and in social media posts.

“I’m frustrated with how poorly Placer County has managed the millions of dollars going into this program. They spent so much to house so few,” Grand said. “They could have invested into undervalued areas where the homeless are more concentrated. Investment there could have beautified neighborhoods,” she continued.

“They put our taxpayer money at risk by purchasing this home with an intended use that is in clear violation of the CC&Rs,” Grand said. Grand and others claim that neighborhood rules — the CC&Rs of their homeowners association — make it illegal to rent to multiple tenants.

“No owner shall be permitted to lease his/her Lot for transient or hotel purposes. No Owner may lease less than the entire lot,” the section they point to states.

Another neighbor said they brought these concerns to The Gathering Inn CEO Keith Diederich and were informed federal fair housing laws override whatever might be in the HOA. The Bee spoke with a lawyer who said the home did not violate any laws. Under California’s “housing first” laws, “tenants have a lease and all the rights and responsibilities of tenancy.”

Diederich said his organization had received no complaints about this new program outside of Grand’s. In June, Grand received a letter from The Gathering Inn’s lawyers asking her to remove inaccurate social media postings.

Cheaper than the emergency room

When Diederich became CEO of The Gathering Inn in 2015, it was just months after an independent auditors report, known as the “Marbut Report,” commissioned by Placer County, found “The Gathering Inn needs to be re-tooled from scratch,” and called TGI’s former policy of allowing the co-mingling children with chronic level adults “very bad practice.”

After the report’s release, Diederich rebranded The Gathering Inn slogan to “providing a hand up, but not a handout.”

The Gathering Inn, formed in 2004 by a group of local ministers as a winter-only shelter serving 40 homeless people per night, now operates the county’s only two homeless shelters — one in Roseville where users stay at local churches each evening and one traditional shelter in Auburn. The Auburn shelter serves 100 people every night and is funded by Placer County.

The suburban home program is a sharp departure for the organization, but Golling, program director for The Gathering Inn, said people come around when they educate themselves about how it works: “Things can be better when we’re way less tribalistic with things.”

As for whether Placer County officials gave adequate notice to residents, Diederich, said, “I think that is a great question for Placer County, as it relates to the expectations of the program when we were setting up and how that communication either flowed or didn’t flow, and I’ll leave it at that.”

“The County is not required to provide notification prior to the purchase of these permanent supportive homes, which are purchased by County contractors,” said Katie Combs Prichard, the Placer County spokeswoman for health and human services. “The County Board of Supervisors approved of the contracts between the County and these Permanent Supportive Housing contractors at public Board meetings.”

Funding in part came from a $1 million grant from Sutter Health, as well the Whole Person Care program and the Mental Health Services Act. The Sutter Health Foundation has donated at least $2 million to Whole Person Care, underscoring the financial incentive hospitals have to reduce the treatment of homeless patients.

Geoff Smith, program manager for the Whole Person Care program, said finding permanent supportive housing reduces ER visits and contact with law enforcement. A 2017 study between the UC Irvine and United Way in Orange County found the cost of services for permanent supportive housing clients was 50% lower than for the chronically homeless — $51,587 versus $100,759.

“Sometimes I can house a person for an entire year,” said Jennifer Price, who became CEO of Advocates for Mentally Ill Housing in 2010, “for what it costs for them to go to the emergency room for one day.”

Temporary homeless shelters can also drain services. In the city of Sacramento, The Bee found the fire department responded to more than 500 calls for service at its Railroad Drive shelter, many for seizures, drug overdoses and shortness of breath, Roberto Padilla, a firefighter union spokesman, told The Bee at the time.

“It’s a concern to us that it hasn’t been acknowledged that the shelters generate this type of call volume,” Padilla told The Bee. “There’s this thought that by putting people in shelters and providing them services, they will no longer burden the 911 system. It couldn’t be further from the truth.”

‘They seem a little shy’

The Bee found support, or general indifference, for the two homes owned by AMI Housing, the nonprofit that helps the mentally ill. AMI has operated in Placer County since 1992 and now provides more than 200 beds across the county.

“For us, we haven’t had any complaints from neighbors or anything at the new houses,” said Price. “We’ve been doing this for a very long time. We try to find houses where we can have some privacy and not bother neighbors and where our clients can live peacefully.”

Price said that includes finding homes that aren’t built too close to other neighbors or schools, and have easy access to transportation and grocery stores so the residents can have a sense of independence.

In interviews with The Bee, neighbors again complained about not being notified by AMI Housing that the homes were being converted, but otherwise said the residents were quiet, even shy, they said. Since AMI Housing acquired the home in December there have been five police service calls to the home.

AMI Housing owns another single-family home in Rocklin on Princess Court. Over the last two years, there have been 15 police service calls to that home, which AMI Housing purchased in November of 2017. Those calls include seven for welfare checks, two for verbal disturbances, one for trespassing, one “cellular 911 call”, one “citizen assist,” one mental case, one missing adult report, and one “out for investigation.”

Princess Court neighbor, Sheri Katz, said she was happy with the operation. She said AMI Housing put up a new fence between the properties without charging her.

“We’ve had great experiences. They’ve been very quiet. We’ve had no problems with them at all,” said Katz. “These people are super quiet. They say hello and keep to themselves. They seem a little shy.”

Matt Kreiser is a reporter for The Beacon Project, the student journalism initiative supported by the University of Southern California Annenberg School for Communication and Journalism. His work appears in The Sacramento Bee.