Planets dance amid eclipses and meteor showers this spring. Don't miss out!

Bright planets, conjunctions, occultations, eclipses, and meteor showers. They're all on tap for the spring season!

The nights may be growing shorter now, but with the weather gradually warming up, spring is a great time for stargazing and night sky viewing. And it's a good thing because there is plenty to see in the months to come.

Here's our complete guide to the astronomical events of Spring 2023.

March 20 — Equinox

March 20~June 21 — Saturn visible in the eastern pre-dawn sky

March 20-June 21 — Mars visible in the western sky after sunset

March 20~24 — Venus and Jupiter in the western sky just after sunset

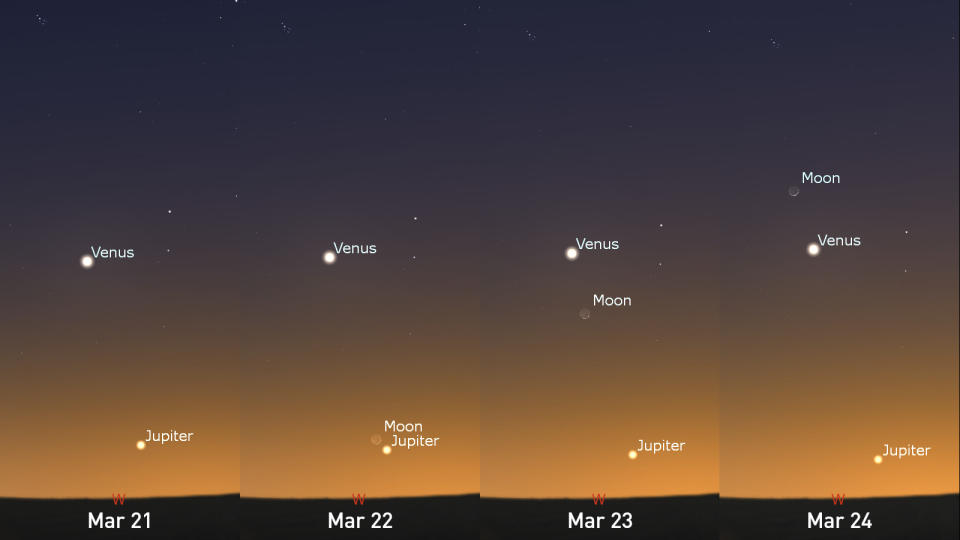

March 22~23 — Crescent Moon joins Venus and Jupiter in the western sky

March 24~31 — Mercury joins Venus and Jupiter in the western sky

April 1~24 — Mercury and Venus in the western sky after sunset

April 5-6 — Full Pink Moon

April 11 — Mercury reaches its highest point in the western sky

April 20 — Hybrid Annular-Total Solar Eclipse

April 21 & 22 — Crescent Moon joins Mercury and Venus in the western sky after sunset

April 21-22 & 22-23 — Lyrid meteor shower peaks

May 5-6 — Full Flower Moon and Penumbral Lunar Eclipse

May 4, 5 & 6 — eta Aquariid meteor shower peak

May 15~June 21 — Jupiter visible above the eastern horizon, pre-dawn

May 17 — Crescent Moon occults Jupiter

May 17 — "Double Shadows and Transits" 'season' begins on Jupiter

May 24~June 21 — Mercury visible above the eastern horizon, pre-dawn

May 29 — Mercury reaches its highest point above the eastern horizon

May 30~June 21 — Mars and Venus together in the western sky after sunset

June 4-5 — Full Strawberry Moon

June 4 — Venus reaches its highest point above the western horizon

June 19 & 20 — Mars, Venus, and Crescent Moon line up in the western sky

June 21 — Solstice

Note: where a ~ appears between the dates in the above table, these are rough estimates which may differ slightly based on location or what time you are observing.

Visit our Complete Guide to Spring 2023 for an in-depth look at the Spring Forecast, tips for planning for it and much more!

Equinox

On March 20, at precisely 21:25 GMT (5:25 p.m. EDT), the Sun will cross the celestial equator, headed north, as observed from Earth's surface. This will usher in Spring in the northern hemisphere, while the Fall season will begin in the southern hemisphere.

The Planets

Throughout the season, Mars will be in the western sky each night, and watch for Saturn in the eastern sky, pre-dawn, each morning.

At the beginning of March, we were treated to an extraordinary conjunction of the brightest planets in the night sky — Venus and Jupiter. Although the two have moved apart in the days since, they will still be visible in the western sky after sunset as we transition into spring. In addition, the Crescent Moon will pass by them in the first few days of the season.

Venus, Jupiter, and the Crescent Moon in the western sky from March 21-24, 2023. Credit: Stellarium/Scott Sutherland

Through the end of March, as Jupiter moves closer and closer toward the horizon, the planet Mercury will pop up in the evening to join them.

Then, Mercury and Jupiter will cross paths, with Jupiter eventually setting beyond the horizon, leaving only Mercury and Venus together for most of April.

Venus, Jupiter, and Mercury in the western sky from March 26-29, 2023. Credit: Stellarium/Scott Sutherland

While they won't come as close together as Venus did to Saturn and Jupiter, watch for Jupiter and Mercury to be right next to each other along the western horizon on March 27.

Jupiter Occultation

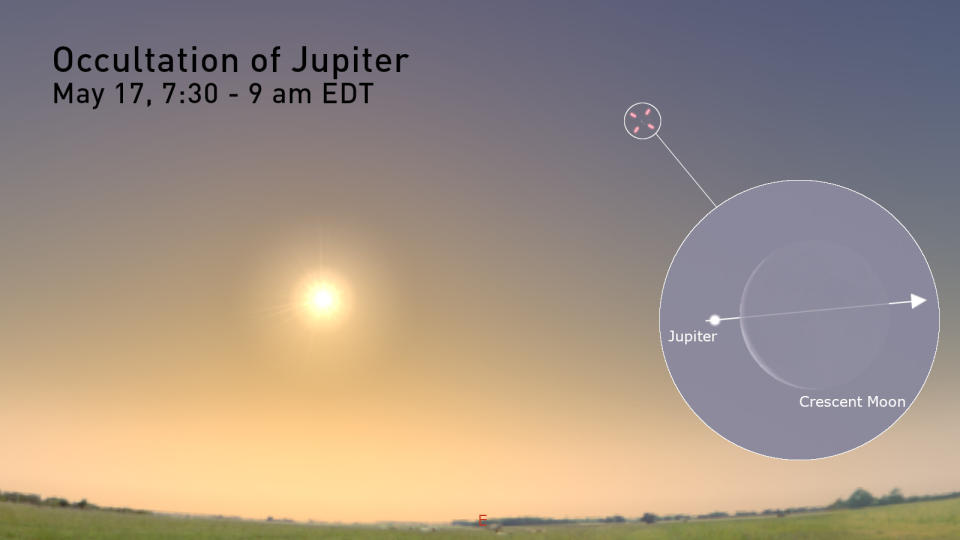

Even though Jupiter slips beyond our view for most of April and the first half of May, when it returns in the eastern sky we have a chance to see a very cool event. On the morning of May 17, as the giant planet hovers above the eastern horizon, the Crescent Moon will pass in front of it, in an 'occultation'.

Due to the timing, this will be a challenging event to see, as it occurs after sunrise across Canada. However, if you have a telescope or a good pair of binoculars, Jupiter and the Moon should be bright enough to still pick out, provided you know where to look.

Note: Be extremely careful not to point your telescope or binoculars at the Sun at any time.

This view of the sky shows the location of Jupiter and the Crescent Moon at the start of the May 17 Occultation of Jupiter, as seen from southern Ontario. The inset image reveals a closeup look, as it may look through a telescope. The exact path of the occultation depends on the location of the observer. Credit: Stellarium/Scott Sutherland

From around 7:30 a.m. EDT to about 9 a.m. EDT, you can watch Jupiter disappear behind the Moon and then reappear again. As this will occur simultaneously for everyone across the country, adjust the starting time to your local time zone — 9 a.m. NDT, 8:30 a.m. ADT, 6:30 a.m. CDT, 5:30 a.m. CST/MDT, 4:30 a.m. PDT. Also, the farther west you are, the closer Jupiter and the Moon will be to the eastern horizon. Thus, observers located in valley communities in British Columbia will likely have their view obstructed by mountains.

Shadows and Transits on Jupiter

If you have a telescope with a large enough aperture (say, at least 90 mm or 3.5 inches) and enough magnification (from 100x to 150x) that you can see the cloud bands of Jupiter, zoom in as far as you can, both before and after the occultation for a special treat.

You may be able to see shadows of some of the planet's largest moons passing across the cloud tops. With an even better telescope, you may even spot the moons themselves transiting in front of the planet!

The panels in this image show closeup views of Jupiter, before the May 17 occultation (left) and after (right), revealing the Galilean moons Io and Europa, as well as their shadows passing over the planet's cloud tops. Credit: Stellarium/Scott Sutherland

According to the Royal Astronomical Society of Canada Observer's Handbook 2023, these May 17 shadow and transit events are the first of a dozen that are expected take place on Jupiter between mid-May to late June. Some of these transit events will occur when Jupiter is below the horizon for observers in Canada, but look for Jupiter on the mornings of May 22, 24, and 31, as well as June 7 and 18.

Full Moons and Eclipses

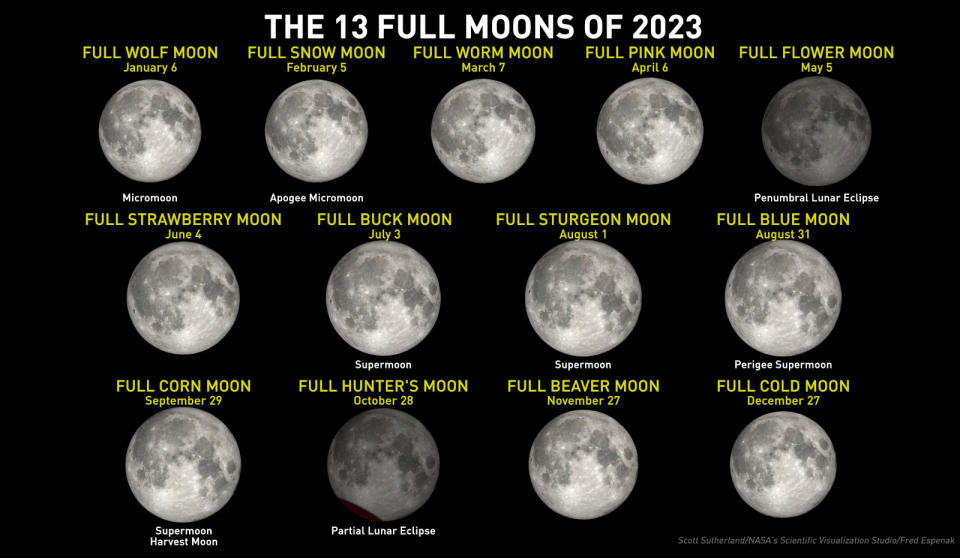

There are three Full Moons in the Spring of 2023 — the Full Pink Moon on April 5-6, the Full Flower Moon on May 5-6, and the Full Strawberry Moon on June 4-5.

The Full Moons of 2023. Credit: Scott Sutherland/NASA's Scientific Visualization Studio/Fred Espenak

Additionally, there are two eclipses during the season.

'Hybrid' solar eclipse

First, on the night of April 19-20, the Sun, Moon and Earth will line up to produce a rare 'hybrid' solar eclipse.

No, you didn't read that wrong. This solar eclipse is timed to be visible on the other side of the world from here in Canada. The path of greatest eclipse for this event stretches from the Indian Ocean, across northwestern Australia and Indonesia, to the Pacific Ocean. So, if we want to see it from this side of the world, we must stay up late on the night of April 19. The eclipse begins at around 9:34 p.m. EDT on April 19, peaks around 12:16 a.m. EDT on April 20, and ends around 2:59 a.m. EDT.

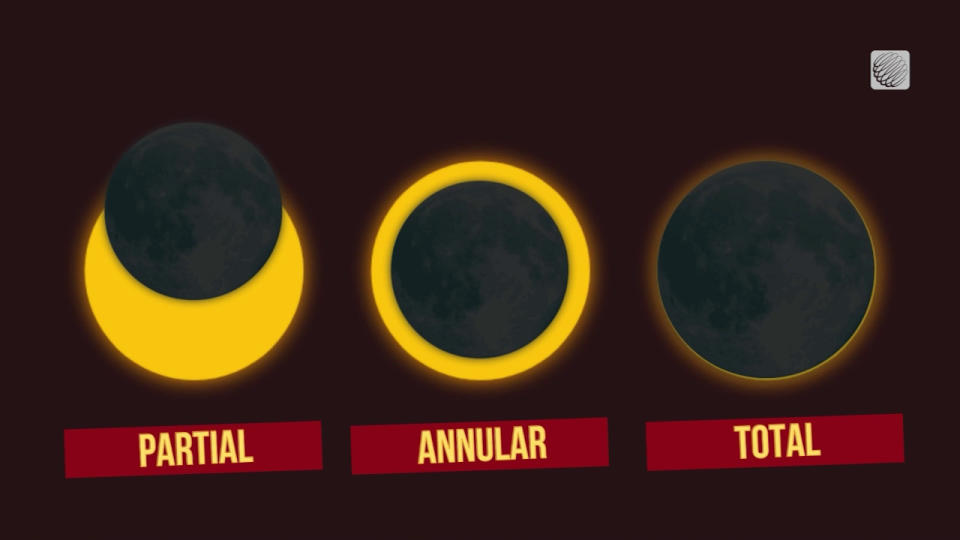

Also, while solar eclipses tend to fall into one of three categories — partial, annular ("ring of fire") or total — this is a special case. The eclipse starts out as annular, changes into a total solar eclipse, and then switches back to an annular eclipse for the end.

Whether we see an annular or total solar eclipse depends on the exact distances between the Sun, Earth and Moon during the event. For a total eclipse, the Sun and Moon are at just the proper distance from Earth that it appears as though the Moon is the same size or bigger than the Sun. During an annular eclipse, either we are closer to the Sun, or the Moon is farther away from us, making the Moon appear smaller than the Sun, which leaves the characteristic 'ring of fire' around the Moon's edges.

Hybrid eclipses occur when the relative distances put the Moon's relative size right on the cusp so that it transitions from one type of eclipse to another during the event.

Penumbral Lunar Eclipse

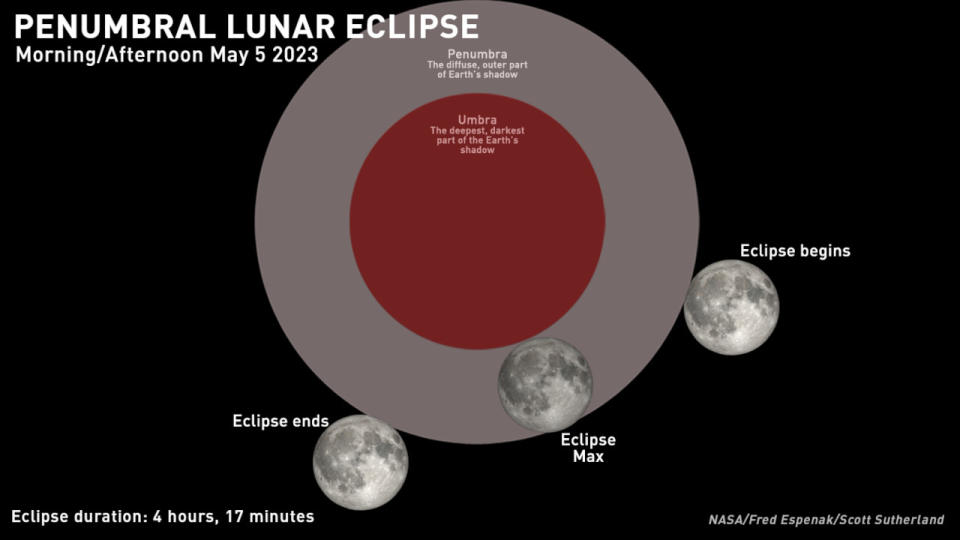

On the 5th of May, the Full Flower Moon will pass through Earth's shadow, resulting in a lunar eclipse. However, it will only be crossing through the outer portion of the shadow — the diffuse penumbra. So, rather than turning a dusky red colour, as it does during a total lunar eclipse, the Moon will dim slightly during this penumbral eclipse.

Also, the event's timing has it taking place during the day for those of us here in Canada.

The path of the Moon during the May 5, 2023, penumbral lunar eclipse. Credit: NASA/Fred Espenak/Scott Sutherland

There is the possibility that someone will live stream the event. Unfortunately, it will be quite challenging to notice the slight dimming of the Moon's light as it passes through the penumbra.

Lyrid meteor shower peak

On April 22, the annual Lyrid meteor shower reaches its peak.

Lyrid meteors can be spotted in the night sky anytime between April 14 to 30, streaming away from their 'radiant' point near the constellation Lyra (look for the bright star Vega to guide you). The best time to view the Lyrids is on the three nights around its peak.

The radiant of the Lyrid meteor shower around midnight, local time, on the night of April 22, 2023. Credit: Stellarium/Scott Sutherland

This year, the view of this meteor shower is supposed to be excellent, as it peaks just a couple of days after the New Moon. With only a thin Waxing Crescent Moon setting shortly after sunset, there will be little competing light in the sky.

Lyrid meteors originate from a stream of dusty, icy meteoroid debris left behind by Comet C/1861 G1 Thatcher. As Earth passes through this stream, the tiny meteoroids slam into the top of the atmosphere at speeds of around 100,000 km/h, turning the air in their path into white-hot plasma. This causes the meteor flash we see in the sky, which winks out either when the 'push-back' from the air sufficiently slows the meteoroid or when the meteoroid completely vaporizes.

The stream of debris from Comet Thatcher is relatively sparse. Thus, even at the shower's peak, the Lyrids only deliver around 20 meteors per hour. Most viewers typically see about half that number.

However, a smattering of slightly larger meteoroids is embedded within the comet's stream. When those hit the atmosphere, they produce bright fireballs!

The Lyrid radiant is up all night, so we can view this shower at any time after sunset (provided the weather is good). Be sure to get away from city light pollution to get the best show, and try to keep sources of light (even the Moon) out of your direct line of sight. More on this below.

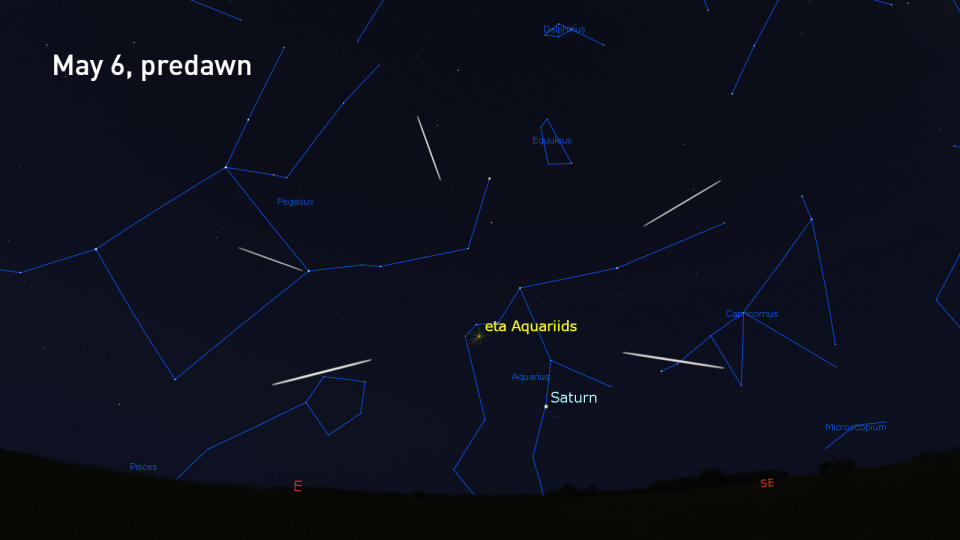

eta Aquariid meteor shower peak

Every year, from late April through the month of May, Earth passes through a stream of ice and dust left behind by Halley's Comet. The resulting meteor shower, known as the eta Aquariids, is active from around April 19 to May 28, and in 2023 it peaks on the nights of May 5 and 6.

The radiant of the eta Aquariid meteor shower, at roughly 4:30 a.m. local time, on May 6. Credit: Stellarium/Scott Sutherland

The best time to see the eta Aquariids is in the hours just before dawn on both May 5 and May 6, since the radiant only rises above the eastern horizon at that time.

Unfortunately, the meteor shower's peak occurs just one night after the Full Moon. This typically reduces the number of meteors we see, as the light from the Moon spoils our night vision.

The eta Aquariids typically produce around 50 meteors per hour under ideal conditions (clear, dark sky, with the meteor shower radiant directly overhead). However, most observers see a couple of dozen per hour, and the bright moonlight may cut that down to around 10-15 per hour.

There is an exciting twist to the story of the eta Aquariids this year, though. The International Meteor Organization says that we may pass through a slightly denser part of Comet Halley's debris trail around the meteor shower's peak. Although there's no information about exactly how many meteors we might see due to this, they suggest watching for elevated activity on the nights of May 4, 5, and 6. Any enhanced activity that does occur could, perhaps, cancel out the effects of the Moon.

This graphic shows the orbit and debris stream of Comet Halley, noting the direction the stream is moving, with the "inbound" producing the October Orionids and the "outbound" resulting in the May eta Aquariids. Credit: meteorshowers.org/Scott Sutherland

The eta Aquariids don't tend to have bright fireballs, as the Lyrids do. However, they do produce a remarkable phenomenon due to their exceptional speed, though, known as persistent trains.

When a typical cometary meteoroid hits the top of Earth's atmosphere, it moves fast enough to produce a meteor flash (as mentioned above). However, the particles in the eta Aquariid stream hit Earth's atmosphere travelling at nearly two and a half times as fast!

As Comet Halley meteoroids streak through the air at 240,000 km/h, there are the usual brief meteor flashes, but they can also produce a bonus. After some meteors wink out, a glowing trail is left behind in their wake, which can float in the air for minutes or even hours.

Watch below to see a persistent train from a different meteor shower

These persistent trains have only rarely been recorded. As a result, scientists are still figuring out what causes them. There are two possible explanations, though.

The first is that the meteoroids travel fast enough to strip electrons from the air molecules, leaving them in an ionized state. Then, as the air molecules snatch up stray electrons from their surroundings, they release energy in the form of light. Since this process can take much longer than the original meteor flash, the 'train' appears fainter and persists for some time after the meteor flash ends.

The other idea involves what's known as 'chemiluminescence'. Metals vaporizing off the fast-moving meteoroid's surface can chemically react with ozone and oxygen in the air to produce a glow.

One of these explanations may account for persistent trains, or both may cover different occurrences at different times and even between individual meteors. It will take more sightings of these to explain them fully.

Tips for meteor shower watching

Meteor showers are events that nearly everyone can watch. No special equipment is required. In fact, binoculars and telescopes make it harder to see meteor showers, by restricting your field of view. However, there are a few things to keep in mind so you don't miss out on these amazing events.

The three best practices for observing the night sky are:

Check the weather,

Get away from light pollution, and

Be patient.

Clear skies are essential. Even a few hours of cloudy skies can ruin your chances of watching an event such as a meteor shower. So, be sure to check The Weather Network on TV, on our website, or from our app, and look for my articles on our Space News page, just to be sure that you have the most up-to-date sky forecast.

Next, you need to get away from city light pollution. If you look up into the sky from home, what do you see? The Moon, a planet or two, perhaps a few bright stars such as Vega, Betelgeuse and Procyon, as well as some passing airliners? If so, there's too much light pollution in your area to get the most out of a meteor shower. You might catch an exceptionally bright fireball if one happens to fly past overhead, but that's likely all you'll see. So, to get the most out of your stargazing and meteor watching, get out of the city. The farther away you can get, the better.

Watch: What light pollution is doing to city views of the Milky Way

For most regions of Canada, getting out from under light pollution is simply a matter of driving outside of your city, town or village until a multitude of stars is visible above your head.

In some areas, especially in southern Ontario and along the St. Lawrence River, the concentration of light pollution is too high. Getting far enough outside of one city to escape its light pollution tends to put you under the light pollution dome of the next city over. The best options for getting away from light depend on your location. In southwestern Ontario and the Niagara Peninsula, the shores of Lake Erie can offer some excellent views. In the GTA and farther east, drive north and seek out the various Ontario provincial parks or Quebec provincial parks. Even if you're confined to the parking lot after hours, these are usually excellent locations from which to watch (and you don't run the risk of trespassing on someone's property).

If you can't get away, the suburbs can offer at least a slightly better view of the night sky. Here, the key is to limit the amount of direct light in your field of view. Dark backyards, sheltered from street lights by surrounding houses and trees, are your best haven. The video above provides a good example of viewing based on the concentration of light pollution in the sky. Also, check for dark sky preserves in your area.

When viewing a meteor shower, be mindful of the phase of the Moon. Meteor showers are typically at their best when viewed during the New Moon or Crescent Moon. However, a Gibbous or Full Moon can be bright enough to wash out all but the brightest meteors. Since we can't get away from the Moon, the best option is just to time your outing right, so the Moon has already set or is low in the sky. Also, you can angle your field of view to keep the Moon out of your direct line of sight. This will reduce its impact on your night vision and allow you to spot more meteors.

Once you've verified you have clear skies and you've limited your exposure to light pollution, this is where being patient comes in.

For best viewing, your eyes need some time to adapt to the dark. Give yourself at least 20 minutes, but 30-45 minutes is best for your eyes to adjust from being exposed to bright light.

Note that this, likely more than anything else, is the one thing that causes the most disappointment when it comes to watching a meteor shower.

If you step out into your backyard from a brightly lit home and looking up for a few minutes, you might be lucky enough to catch a rare bright fireball meteor. However, it's far more likely that you won't see anything at all. Meteors may be streaking overhead, but it takes time for our eyes to adjust, so that we can actually pick out those brief flashes of light. Waiting for at least twenty minutes, while avoiding sources of light during that time (streetlights, car headlights and interior lights, and smartphone and tablet screens) dramatically improves your chances of avoiding disappointment.

Sometimes, avoiding your smartphone or tablet isn't an option. In this case, set the display to reduce the amount of blue light it gives off and reduce the screen's brightness. That way, it will have less of an impact on your night vision.

You can certainly gaze into the starry sky while you are letting your eyes adjust. You may even see a few of the brighter meteors as your eyes become accustomed to the dark.

Once you're all set, just look straight up and enjoy the view!

Thumbnail image courtesy Canva