'Please have mercy': Minutes before Nathaniel Woods' execution, murder victim's sister begged an Alabama official to spare him

Ten minutes before Nathaniel Woods was scheduled to be executed for his role in the 2004 murder of three police officers, the chief of staff to the governor of Alabama received a desperate phone call from the sister of one of the slain cops.

Her plea: Spare his life.

“He didn’t kill my brother, and he didn’t kill the other officers, may they rest in peace,” Kimberly Chisholm Simmons, the sister of murdered officer Harley Chishom III, pleaded during the call that started around 5:50 p.m on March 5. “I’m asking for mercy, and I believe my brother would want me to take a stance because of the man he was.”

Gov. Kay Ivey’s chief of staff, Jo Bonner, said he would relay the message to other officials and suggested that Simmons should expect a call back.

But the murder victim’s sister never heard from another Alabama official, even after a temporary U.S. Supreme Court stay bought Woods a few more hours. Its justices ultimately elected not to intervene in his execution, and at 9:01 p.m., Woods, 43, died by lethal injection.

The extraordinary 11th-hour phone conversation, which was recorded by Woods’ attorney and shared with USA TODAY, has not been reported.

Video: ‘Trial by Fire’ Star Laura Dern Advocates for Abolition of Death Penalty

The call was the result of back-channel negotiations in which Woods’ attorney, Lauren Faraino, was informed by sources connected to the highest levels of Alabama government within an hour of her client’s scheduled execution that he could be spared if a victim’s family member begged for his life.

For those close to Woods, and undoubtedly the condemned man himself, the failed call for mercy was only one of several moments of emotional whiplash on the last day of his life. The prospect that Woods would be allowed to live was repeatedly held before them and then yanked away.

The Supreme Court stay caused his family members to celebrate, believing he had been spared. His family learned within hours that his execution was still imminent.

Woods’ imam, who was set to witness his execution, said he was sent away from the prison and told he could return if the execution went ahead. But the imam was notified too late, and Woods was executed without his spiritual adviser present.

Woods’s case attracted national attention – including from high-profile supporters such as Martin Luther King III and Kim Kardashian – because of claims of police misconduct, flimsy evidence and poor representation in his 2005 trial.

Prosecutors acknowledged that Woods didn’t pull the trigger that ended the lives of the three police officers, instead convincing a jury that he had lured them into being killed by another man. The confessed shooter, Kerry Spencer, who is himself on death row, has said Woods was “actually 100% innocent.”

It’s unclear what steps Bonner took, if any, after receiving the call from Simmons. He did not respond to an interview request for this story. His cellphone number that Simmons used that night – which Woods’ own sister also said she subsequently called to beg for mercy, and that was then tweeted out to the world by King III – has since been disconnected.

A spokeswoman for Ivey also declined to make the governor available, instead resending a statement she had issued the night of Woods’ execution.

“This is not a decision that I take lightly, but I firmly believe in the rule of law and that justice must be served,” read the statement, adding that the governor’s “thoughts and most sincere prayers are for the families” of the officers. “May the God of all comfort be with these families as they continue to find peace and heal from this terrible crime.”

Not all of Chisholm’s siblings feel the way his older sister Kimberly does about Woods’s execution. At a news conference after the execution, members of Chisholm’s family cheered the outcome.

“One cop killer down as we patiently wait for the next one,” said Starr Sidelinker, sister to Harley and Kimberly.

Faraino, Woods’ attorney, said her client’s last hours alive, while his family hung on every development, were “the cruelest moments I’ve ever been through in my life.”

Simmons’ involvement in the final day of Woods’ life started a few weeks earlier, when she received a letter at her home in Florida from authorities stating that Woods was set to be executed.

Simmons hadn’t closely followed the case since Woods’ conviction, and she said the murder of her police officer brother – whom she called “Buddy" – had fractured her family. Although her sisters were eager for retribution, Simmons felt compelled to send an email to a nonprofit death penalty website with the hope that it might reach Woods before he was put to death.

“I forgive him for any involvement he had personally I don't feel he's guilty as much as Spencer,” Simmons wrote. “Only God knows the truth of what has really happened and if it's in God's plan he will stay his execution. But I want him to know he is Forgiven by me.”

The email was forwarded to Woods’ attorney, Faraino, the day before his scheduled execution. Faraino makes her living in finance, and her pro bono legal work for Woods was a no-frills family affair. Her mother pulled legal files at the courthouse, and her stepfather, Bart Starr Jr. – the son of a revered Alabama and Green Bay Packer quarterback and member of the Pro Football Hall of Fame – worked the phones with well-placed friends to lobby for mercy for the death row inmate.

Starr Jr. was at Faraino’s Birmingham home with less than an hour to go before Woods’ execution when one of those calls bore fruit. A prominent political donor told Starr his brother, an Alabama state senator, had conveyed that government officials might consider a stay if a victim’s family member pleaded for it.

Faraino frantically emailed Simmons: "I am pleading with you, please give me a call.” The victim’s sister readily agreed to ask Alabama authorities to spare Woods’ life.

Faraino's audio recorder caught the frenzied next hour. While Simmons waited on the other line, Faraino dialed numbers to try to reach an Alabama official but found only switchboards and office voicemails.

At about 5:45 p.m. – roughly 15 minutes before Woods’ scheduled execution — Faraino heard Starr Jr. yell out: “What?”

“Oh, no, no, no, no, no,” Faraino said, weeping as she told Simmons, “I think they’re executing him right now.”

But Faraino’s mother informed the lawyer it was actually good news. Supreme Court Justice Clarence Thomas had issued a temporary stay of execution.

Simmons began celebrating. “God loves Nathaniel Woods,” she said.

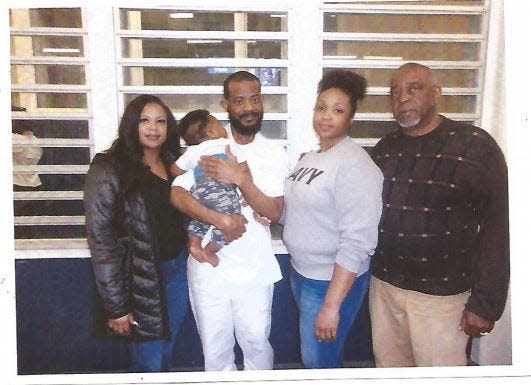

Members of Woods’ family learned of the stay from their cellphones and interpreted it as a lasting measure. Earlier that afternoon, Woods, seven family members and his imam had joined him for what was supposed to be his last meal, and he had for the first time met his grandson. Now, his family and friends were overjoyed that it wouldn’t also be the last time.

“I’m shaking, I’m just so excited I don’t know what to do, you know?” family friend Jasmine Walters said moments after they learned of the stay. “I’m just so grateful. I’m so, so grateful.”

But Faraino was aware that the Supreme Court’s stay was only an interim step to allow the justices a couple of hours to decide whether to intervene, which was a long shot.

Her efforts to reach an Alabama official before the stay might be lifted got a break when her stepfather ran to her office with Bonner’s cellphone number, obtained via a former University of Alabama football player.

After Bonner picked up, he declined to put Gov. Ivey on the phone with Simmons, saying she was on another phone call.

Simmons emphasized to Bonner that all she was asking for was a renewed look at Woods’ case. “I think they need to go over the evidence that they have brought forth,” Simmons said. “I mean, it’s not going to hurt nothing.”

“I’m begging the courts,” she added. “Please have mercy.”

Bonner, a former congressman, responded dispassionately. “Have you communicated in writing this request?” he asked. Bonner said that though he wasn’t doubting Simmons was who she said she was, her identity may have to be verified. “Because of the severity of this we have gotten calls from all over the country from people purporting to know things that they may or may not know.”

But Bonner said he would convey Simmons’ plea to the state attorney general and the governor’s legal counsel. He took down her number and said representatives from those offices “may give you a call to get some additional information.”

Two hours passed with no Alabama official calling Simmons. At 8:06 p.m., the Supreme Court issued a one-sentence decision denying Woods’ stay of execution, removing the only remaining obstacle to his death.

Woods’ sister, Pamela, said she also reached Bonner on the cellphone number, asking to speak to the governor. “I begged, I screamed, I cried,” Pamela Woods said. “He would not let me talk to her. He just said ‘No.’ I begged him, screaming, ‘Please, let me speak to her,’ and he told me, ‘No.’ And he hung up in my face.”

Simmons said she could tell during her conversation with Bonner that it probably would have little effect. “I sensed, you know, ‘You’re not going to stop this, lady,’” she said. “They’re going to take this man no matter what I say. It’s already in their hearts to kill him.”

Nathaniel Woods’s imam, Yusef Maisonet, said he was told to leave the prison after the Supreme Court stay and to expect an official to call him and escort him back in if the execution went forward that night.

But the imam said nobody called him until shortly before Woods was returned to the execution chamber at close to 9 pm. By then, thinking the execution was off, Maisonet had returned to his home in Mobile, more than 50 miles away.

“I feel that they did purposefully keep me out” of the prison for Woods’ execution, Maisonet told USA TODAY last week.

Samantha Rose, a spokeswoman for the Alabama Department of Corrections, disputed Maisonet’s account. She said in a statement that after Maisonet was asked to wait in a certain area for the execution, he “elected to leave this location on his own accord without speaking to security staff. When security staff arrived to take him to the execution, the Imam was no longer onsite … We will not speculate on the reasons why this Imam chose to leave when he did.”

Maisonet said he had spoken at length with Woods about topics including what he wanted done with his body. Before the day of the execution, Maisonet wrote to the Holman warden requesting that Woods’ body not be autopsied “since it is against our religious beliefs and the cause of death will be known.”

Alabama officials nonetheless performed the autopsy March 6, according to Fairano. Alabama corrections department spokeswoman Rose said that decision was “at the direction” of Escambia County District Attorney Stephen Billy.

Billy’s office did not respond to a message seeking comment for this story. In a letter to Faraino before the autopsy was completed, Billy said it was his “policy to order autopsies on all executions … to confirm the cause and manner of death.”

“It is not my intention of changing my position on this matter,” Billy wrote to the lawyer, “and would appreciate you not contacting my office again regarding this issue.”

Faraino said she has not been informed of what the coroner found to be the official cause of Woods' death.

This article originally appeared on USA TODAY: Before Nathaniel Woods' execution, sister of victim begged for mercy