Podcast exposes horrors of Mt. Meigs reform school in Alabama

- Oops!Something went wrong.Please try again later.

The sun beats on vegetables and cotton plants. Children, all Black, work up and down the rows gathering crops. If they don’t produce the quota, they get beaten. They might get beaten even if they do. Sexual assault is rampant, education nearly nonexistent, and food, when edible, is not enough to sustain the physical labor they’re subjected to. If they run away, police catch them and bring them back where they are often publicly tortured.

If this sounds like slavery to you, it should. But this was the mid-1960s, and it was just down the road.

For decades, Black children were abused and traumatized at a reform school in Mount Meigs, an unincorporated part of the county about 15 miles from Montgomery. The little-told story of the campus and how it affected the children detained there is the subject of a new podcast, “Unreformed: the Story of the Alabama Industrial School for Negro Children,” by journalist Josie Duffy Rice.

The history of the school and the abuses suffered there haven’t been publicized much, even in Montgomery. There are different reasons for that, not the least of which is that these students were Black and sent there more than half a century ago. The few times the school is brought up, it’s often mentioned as the place where Satchel Paige — the great Negro League and Major League pitcher and one of Alabama’s most famous native sons — spent six years of his life.

Duffy Rice’s podcast shares the horror stories that former residents endured. It’s the result of more than a year of research and discussion with former residents and employees at Mt. Meigs who reveal how those scars stick with them today. The story’s scope is bigger than that though, Duffy Rice said.

“When I first started this project, I thought it was about school. Now, I kind of feel like it's about a city, about a town, about the history of how Alabama thought about education, how they thought about Black people, how they still do,” she said in an interview.

How to listen

“Unreformed” is available on most streaming services, including iheartpodcasts, Apple, Audible, Spotify, and Stitcher. Episodes are released each Wednesday, and this week’s will be the fifth episode of the series.

Where children are criminals

A few minutes into the first episode, Duffy Rice lays out the central lie of the campus in the past: “Technically, Mt. Meigs was a reform school for kids. But what I’ve discovered is that it wasn’t really a school at all.”

Those who knew Mt. Meigs well then describe it in their own words: “Mt. Meigs was patterned after slavery,” one man says; another man calls it a “slave camp”; others call it a plantation, a “prison for teens” and a “penal colony for children.”

The Black educator Cornelia Bowen opened the reform school in the early 20th century at the recommendation of Booker T. Washington, who saw the need for an alternative to adult prison for Black children who got into trouble. In its early years, the reform school seemed to live up to its rehabilitative ideal.

But after the campus was sold to the state of Alabama in 1911, its focus shifted to punishing children, many of whom were sent to Mt. Meigs for what is essentially being a teenager — listing their offenses as laziness or loitering. The cruelty seemed to have worsened over the years, and by the 1960s, it was horrific, Duffy Rice says.

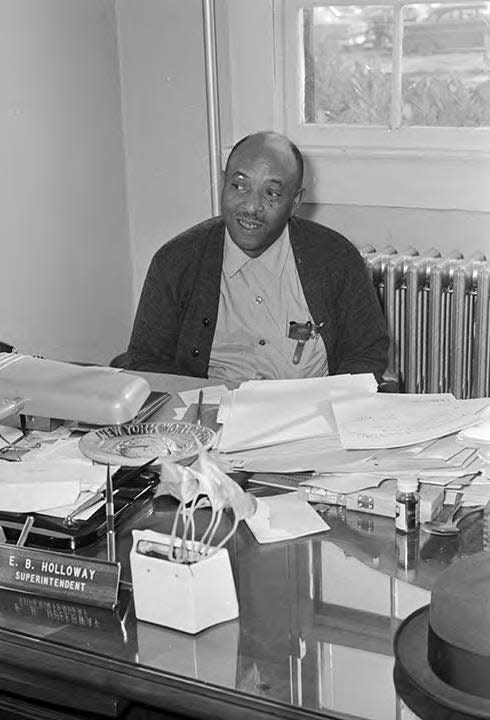

By design, the campus functioned more like a prison than a school. In preparing Superintendent E.B. Holloway for the job, he wasn’t taught how to work with children. He was taught how to deal with inmates at Kilby Correctional Facility.

“They were children. But to the state of Alabama, they were criminals all the same,” Duffy Rice says in the second episode of the series.

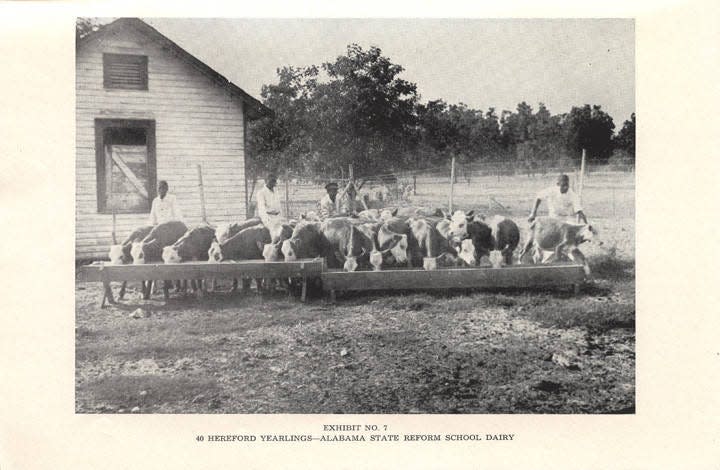

At the school, students worked outdoors for hours picking cotton and vegetables, tending livestock and doing custodial work. At night they went back to dilapidated living quarters and ate measly portions of food from a kitchen former residents said was filled with roaches. One man remembers children so hungry they ate corn out of cow manure.

The physical abuse was coupled with emotional and psychological abuse from the school’s guards.

“I was told in Mt. Meigs that we’ll never be anything, that we’ll never amount to anything,” one woman who attended the school says in the first episode.

More:How newly freed slaves created the South's public school systems

Leaving Mt. Meigs: Murder, beauty and hope

The trauma that many residents experienced stuck with them for the rest of their lives. Many of them were transformed from children, troubled or not, into “monstrous versions of themselves.” Duffy Rice said an “enormous amount” of the former residents are in prison for life or on death row.

One man, Jesse James Andrews, brutally killed three people in California. Part of his legal defense rested on the harm that Mt. Meigs had done to his psyche, Duffy Rice found.

Numerous psychologists testified that he had post-traumatic stress disorder and other psychological damage from his time there. His attorneys argued it was strong enough mitigating evidence to keep him from receiving the death penalty. Andrews is sentenced to life in prison for life without the possibility of parole in California.

There are others, though, who managed to turn the pain into something beautiful. Famed artist Lonnie Holley was in Mt. Meigs and is one of the podcast’s main characters. He turned one particularly painful memory of watching his blood drip after a public beating into the piece, “Blood on the Rock Pile.”

Duffy Rice said that many people she spoke with, including those in prison, have been able to forgive those who harmed them at Mt. Meigs.

“Part of the story is hopeful because it does show how some people come out of this institution and try to make something like beautiful from it,” Duffy Rice said. “A lot of them have demonstrated a capacity for change, and a capacity for forgiveness. And on some level, for vulnerability, I think that is pretty beautiful.”

A new way to read:The Montgomery Advertiser app now gives you access to 200 e-Newspapers

The importance of learning and dealing with the past

Duffy Rice is from the South and currently lives in Atlanta. She hadn’t heard about the “trauma machine” that was Mt. Meigs before she got an email asking her to work on the podcast. Some of you probably haven't heard of it before now.

And that’s a bit scary to think about, Duffy Rice said.

“One thing I'm really realizing is how many more stories like this there are to tell,” she said in an interview. “It's important to try to look at what juvenile reform institutions are around you, or were around you, because these places have impacted a lot of lives.”

And for the most part, Alabama hasn’t acknowledged the harm it caused thousands of people at the school. Duffy Rice said she sees that as part of a broader effort to avoid having tough conversations.

“It's fair to feel uncomfortable talking about tough things that are part of our histories,” she said, “but that is part of the job. It's part of being a good citizen, and it's part of being a good Alabamian. Part of being a good American is to be able to really grapple with history and try to make sure we don't make the same mistakes again.”

Evan Mealins is the justice reporter for the Montgomery Advertiser. Contact him at emealins@gannett.com or follow him on Twitter @EvanMealins.

Your subscription makes our journalism possible. Subscribe today.

This article originally appeared on Montgomery Advertiser: Podcast exposes horrors of Mt. Meigs reform school in Alabama