A poet’s life from Vietnam to NC State, told through stories and songs and scars

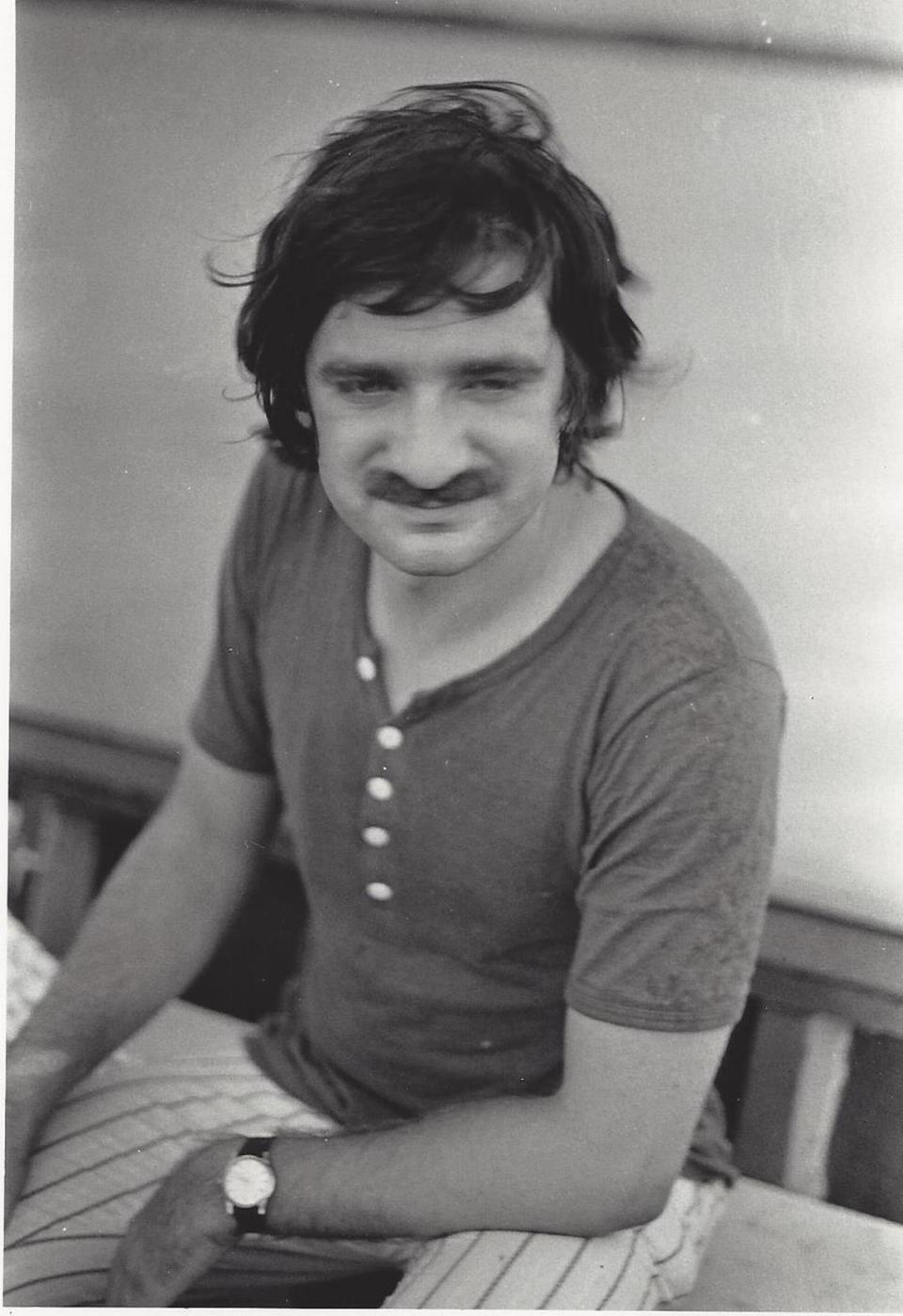

As an American poet, John Balaban started his writer’s journey in the public library of his youth — a bookworm child surviving a Philadelphia neighborhood so rough the local boys threw ice balls at police cars for fun and once shot him in the stomach with a hunting arrow.

Just out of high school, finally free, he hitchhiked his way across the 1960s with his poet’s eye taking notes from the passenger seat: the preacher who offered sleeping space in his church; the hooligans with black eyes who picked him up on their way to surrender at the police station; the dog-fighter with his beasts chained up in the back.

Then, like so many men of his generation, Balaban found himself pulled into Vietnam — three times in all, twice as a conscientious objector in the volunteer services. In those war years, he experience the Tet Offensive bombing, took a hunk of shrapnel in his shoulder and met children with both legs shot off.

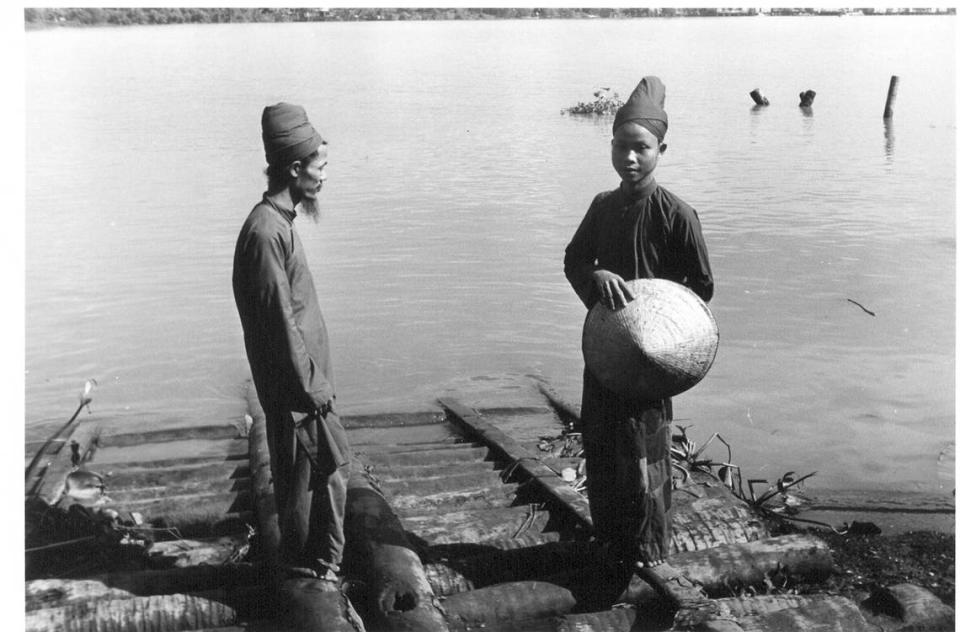

Through all of it, he learned Vietnamese, scribbled observations in his notebook, and recorded the voices of the rice farmers and fishermen he met along the Mekong River — the core of his life’s work.

‘An American being an American in America’

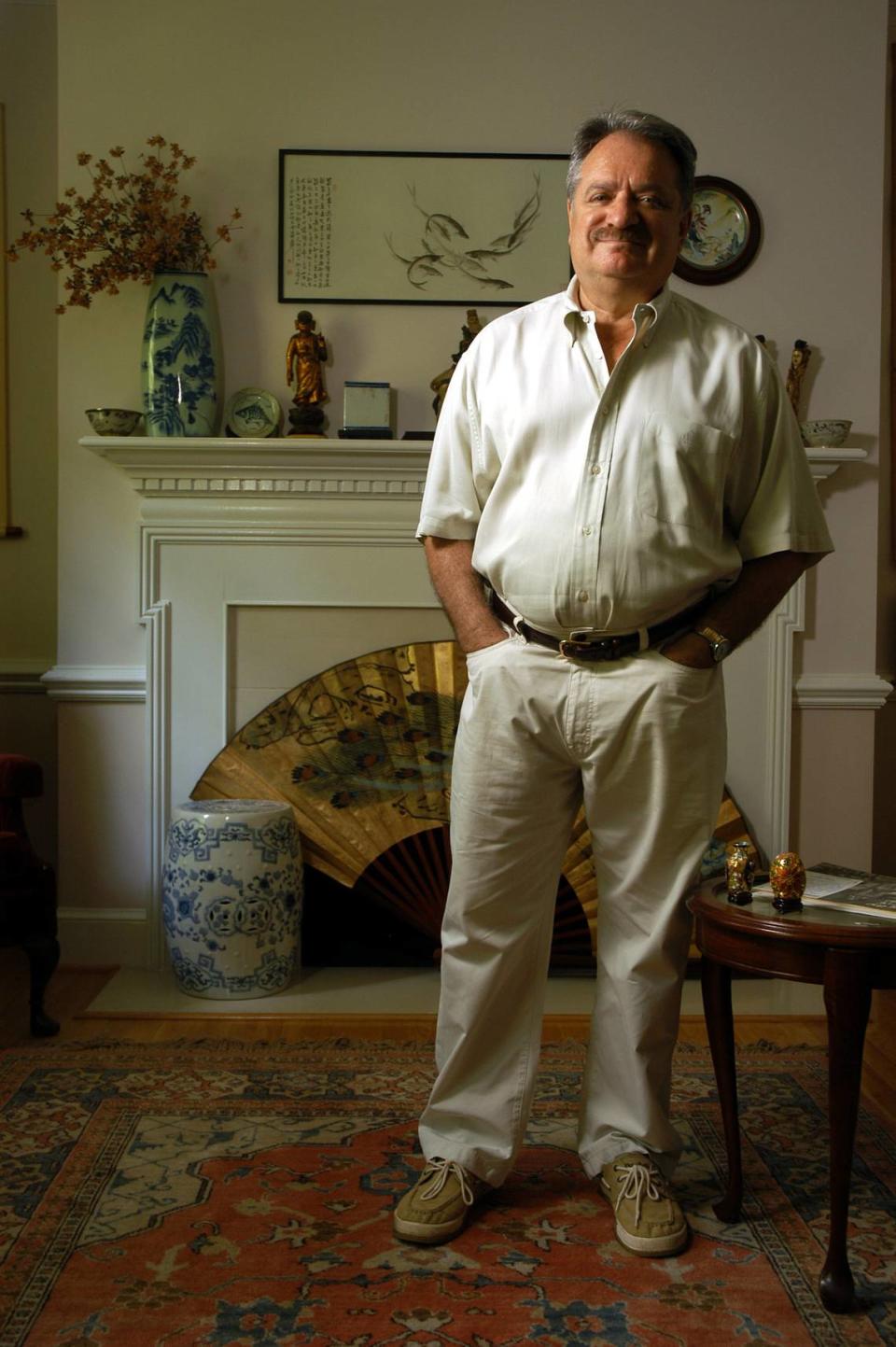

And now at 80, a retired English professor from NC State University, his words fill the pages of “Passing Through a Gate,” his collected works. At 259 pages, it follows his observations from Saigon to Atlantic Beach.

“The subject matter is an American being an American in America,” he said from home in Cary last week. “What does that mean, morally? It’s writing without preaching, letting the reader see what you’re seeing.”

Right away, Balaban’s book deserves notes because it contains translations of ca dao — pronounced ka-yow — the Vietnamese folk poetry never written in English before Balaban captured it. Those translations also represent the first time ancient Vietnamese characters have been set in digital type — meaning no keyboard keys existed for them before now.

His work travels to scenes of more contemporary trauma than those he saw in Vietnam, notably in “A Finger,” in which Balaban draws his focus to a single severed appendage found in the rubble.

But the heart of “Passing Through” takes place in the war zone of Balaban’s youth. A student at Penn State and then Harvard University, he initially tuned out the noise of Vietnam, immersed in verse a thousand years old.

“I was trying to pay attention to Old English,” he said, “not politics.”

To Vietnam, as a conscientuous objector

Then Defense Secretary Robert McNamara visited Harvard’s campus in 1966, where hundreds of anti-war demonstrators blocked his path insisting he hold a public debate. Undeterred, the defense secretary baited the crowd, telling them he’d been just as radical as a youth, but he’d been more polite. Harvard later sent an apology.

“That made my blood boil,” Balaban said.

Though he had a student deferment, though his number had not been called, Balaban told his draft board he planned to go to Vietnam immediately, as a conscientious objector. He brought along a Quaker elder as a witness, but the boarded needed no such proof of his intentions.

His alternate service began in a rural language school, bombed just days after he arrived, forcing Balaban to walk miles in search of a medic, carrying shrapnel in his shoulder. This led to his second stint as a non-combat volunteer, which involved shuttling wounded Vietnamese children to care in U.S. hospitals.

The girl he remembers best, Balaban said, was discovered in a pile of bodies in her village, just underneath her mother.

“She was the tiniest,” he said.

But even once his service finished, Balaban returned to Vietnam a third time in 1971 — this time armed with a tape recorder. He’d gotten a fellowship from the National Endowment for the Humanities, which allowed him to wander through the war-torn country recording the folk songs he’d heard on the rice plantations and along the river bank.

“What are these people singing in the middle of a war?” he asked himself.

Having learned enough Vietnamese to get by, he wandered on foot as the war raged around him, capturing bursts of gunfire and mortar launches on tape along with the singing voices. He recorded 5-year-old children and wrinkled old men, some of whom knew a handful of songs and some of whom knew hundreds.

Voices from Vietnam

The songs sounded like the blues to Balaban’s American ear, and nobody ever refused him.

“One was a Buddhist monk,” he remembered. “One was secretary to the U.S. consulate in Hue. One was a fundamentalist minister in a village up in the mountains.”

From his living room sofa, five decades later, Balaban recalled recording a tall woman living in a hut on stilts, who collected medicinal herbs and hung them in her rafters for sale.

She told him she’d been mute as a child and her parents thought her insane, so they sought the services of a local faith healer: “The Monk Who Sells Potatoes.”

This monk, Balaban said, plucked a pear tree leaf and placed it on the girl’s tongue, which prompted her to speak at last. The grateful parents then asked the monk what he wanted as payment, and when he pointed to the girl, they gave her away. The woman told Balaban that the monk kept her until she began menstruating, at which point he sent her to a Buddhist nunnery.

“Then I was crazy again,” she recalled, “and I started singing.”

These are the stories Balaban carried home, more vivid than the scars.