A police officer exposed a video showing a death in custody. Now he’s facing prison time.

WARNING: This investigation includes graphic images of police misconduct.

Sgt. Javier Esqueda replayed the recorded images in his mind as he lay awake at night.

A handcuffed Black man, barely conscious, swayed against the back seat of a police squad car. “Wake up, bitch,” an officer said as he slapped the man. The officer clutched at the man’s throat with one hand and pinched his nose shut with the other.

Esqueda counted how long the man seemed to be without air. Twenty seconds, so far.

The officer tried to pull the man’s mouth open. Thirty seconds. Another officer poked a service baton into the man’s mouth, jabbing the insides of his cheeks. One minute.

Finally, the officers pulled out a few small plastic baggies, partially filled with white powder.

One minute, 38 seconds. Esqueda, a former Marine reservist and 27-year veteran of the Joliet, Illinois Police Department, knew that was a long time to hinder someone’s breath, especially someone with drugs in his mouth and in medical distress.

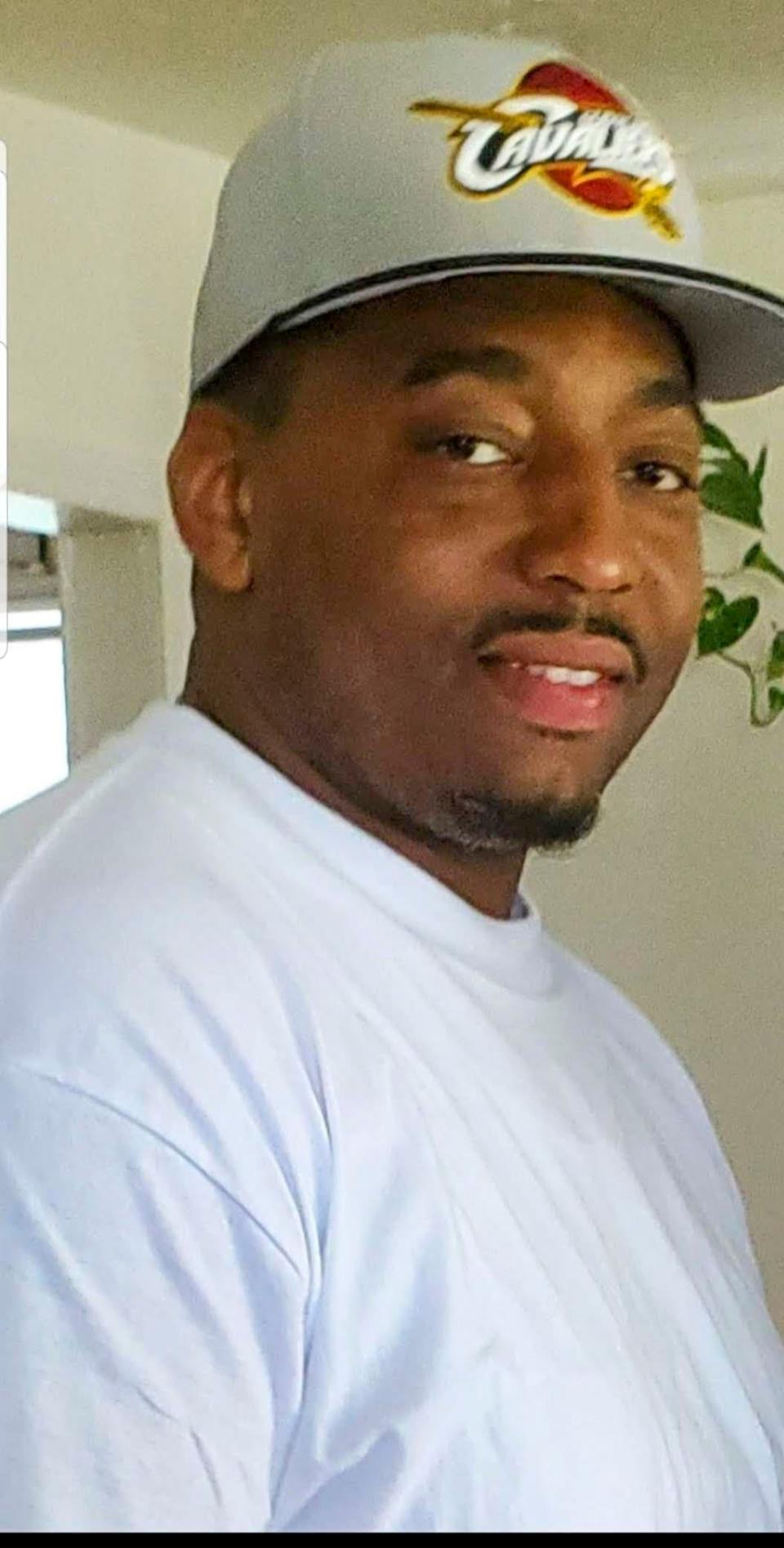

Ten hours after the squad car’s camera recorded the January 2020 incident, Eric Lurry, 37, died of a drug overdose at a nearby hospital. Months went by and the public still had no idea that instead of getting Lurry immediate medical attention, the officers who knew he had swallowed drugs didn’t seem to care. Esqueda had heard a rumor about the video — that it was bad — but didn’t give it much thought.

Then he watched with the rest of the nation as another Black man, George Floyd, was killed in Minneapolis by a police officer. Three officers stood by while Derek Chauvin pressed his knee to Floyd’s neck for nine minutes. Where were the so-called ‘good cops’ to stop this? Esqueda heard people ask.

So in May 2020, Esqueda logged into the department system to watch the video of Lurry’s arrest. He was stunned not only by what he saw but also by how little impact the death in custody seemed to have. It wasn’t in the news. An outside investigation had stalled. The officers were still working as if nothing had happened. Even Lurry’s own family hadn’t seen the video.

It’s a cover-up, Esqueda thought. For weeks, Esqueda agonized over what he should do about it. Finally, he leaked the footage to a local television reporter.

Within days, Esqueda’s bosses suspended him. His friends and peers abandoned him. Even worse, Joliet Police arrested him on felony charges of official misconduct that could land him in prison for up to 20 years. At a hearing scheduled for today, Kendall County Chief Circuit Judge Robert Pilmer could set a trial date.

Help USA TODAY investigate law enforcement’s code of silence

USA TODAY is documenting how law enforcement agencies around the country threaten and retaliate against internal whistleblowers who expose misconduct by their fellow officers. If you have a story about that or know someone who does, we want to hear from you.

In the wake of Floyd’s death, USA TODAY set out to document how law enforcement agencies respond when one of their own exposes police corruption, brutality or other misconduct. Reporters found systemic, unchecked retaliation at departments large and small across the country.

Esqueda’s case emerged as a textbook example of the lengths that some departments — along with prosecutors and other powerful local officials — will go to punish whistleblowers and scare their colleagues into silence. By undermining his department’s carefully crafted narrative around Lurry’s death, Esqueda crossed a sacred line drawn through the world of American policing: the unwritten rule that cops should never snitch on one another.

“I knew it was going to be bad. And I was ready for it to be bad. I knew what I was going up against,” Esqueda said. “But I never thought I was going to be sitting in jail. Not for telling the truth.”

Like many officers accused of misconduct, the Joliet cops involved in Lurry's death faced no criminal charges after prosecutors and the coroner said the officers were not responsible. Internally, the department either cleared them or issued short suspensions. (The officer who put the baton in Lurry’s mouth was fired months later after he was arrested on an unrelated domestic violence charge. The three other officers remain with the agency.)

After Esqueda stepped forward, Lurry’s family filed a lawsuit against the department that claims police contributed to Lurry’s death by failing to immediately get medical assistance once they knew he’d ingested drugs. Community leaders in the small town of Joliet, 45 minutes outside Chicago, have said police misled them by withholding key details about the interaction, reviving suspicions that they played a role in Lurry’s death.

Alan Roechner, who was Joliet’s police chief at the time and ordered Esqueda’s arrest, told USA TODAY he couldn’t say much because Esqueda’s criminal case is still open and prosecutors might call him as a witness. But he said Esqueda is no whistleblower.

Current Joliet Police Chief Dawn Malec said it would be inappropriate for her to comment on Lurry’s death or Esqueda’s charges because of the ongoing civil and criminal cases.

Malec had been scheduled to announce Esqueda’s department punishment at an Aug. 27 hearing. But days after a USA TODAY reporter requested interviews with her and other city officials about Esqueda’s case, she postponed the hearing until Sept. 21.

Malec has concluded the internal investigation and records show she sustained three pages of internal violations against Esqueda — including conduct unbecoming an officer, improper release of evidence, and making a public statement about the department without prior permission from the police chief.

The prosecutors who filed the criminal charges also declined to comment.

Esqueda said it’s clear to him that breaching law enforcement’s code of silence has made him a pariah.

“These were my fellow officers, my friends,” he said. “Now … if something happened to me or if I died, they’d have a party.”

The 62-minute video

For weeks, Esqueda had mostly ignored rumors that a video existed that might cast his police department in a bad light. When another sergeant suggested that he check it out, Esqueda said he wasn’t interested.

But a few days after Floyd’s last moments were broadcast to the world, Esqueda changed his mind.

He logged into the police department’s evidence system with his assigned username and password. If the case was still under investigation, the system would have locked him out of the video, he said. It opened right away.

The 62-minute video begins before 4 p.m. near the intersection of East Washington and South Hebbard Streets in Joilet. Lurry, in a bright red-orange hooded sweatshirt, is standing at the front bumper of a squad car. Two officers — Jose Tellez and his trainee, Andrew McCue — wrestle Lurry to the ground and put him in cuffs, with his hands behind his back. They place him in the back of the squad car.

The video shows Lurry chewing on something. He’s breathing heavily. It’s unclear whether the officers can see what he’s doing, but the audio picks up Tellez saying he believes Lurry might have put “a bunch” of the drugs he had on him in his mouth.

"He’s got some in his mouth,” Tellez later adds about the drugs. “I don’t know how much but he’s still got some in there.”

Esqueda noted that the officers didn’t call for paramedics to bring Lurry to the hospital, as required by department policy when an officer believes someone in custody requires medical attention. Instead, between the time Tellez is first recorded saying he believes Lurry ingested drugs and the time they arrive at the police station, officers left Lurry in the backseat for at least 11 minutes. During much of that time, Lurry is still chewing on something.

By the time they reach the precinct parking lot, Lurry is barely conscious. McCue expresses his disapproval as he tries to get him out of the squad car.

“We’re not doing this today,” the recording captures him saying as he tries to pull Lurry’s feet onto the concrete. McCue rubs Lurry’s sternum but he doesn’t respond, one of four indicators — according to the department’s protocol — that he is suffering from an opiate overdose. Lurry had already displayed at least two other indicators — the presence of drugs and shallow breathing. It is unclear from the black and white video whether Lurry's lips had a bluish tinge, the fourth sign listed in the department’s policy.

Instead of calling for paramedics, Sgt. Doug May slaps Lurry and holds his nose. At some point, May said he saw a bag of drugs in Lurry’s mouth, according to a report later filed by Lt. Jeremy Harrison. That’s when Harrison determined Lurry was suffering a medical emergency.

May’s statement was not recorded, however, because Tellez had turned off the audio by then.

As the video continues, Harrison requests a flashlight or baton to prop Lurry’s mouth open. Officers remove the bags and tell Harrison that Lurry has stopped breathing, according to Harrison’s report. Then Harrison calls paramedics.

Just as he had when he watched Floyd die, Esqueda cried as he saw what happened to Lurry. “But in this case, it was worse,” Esqueda said. “These were officers I knew."

Tellez’s training report didn’t mention that officers had slapped Lurry, restricted his breathing or jammed a baton in his mouth, Esqueda said. It simply said Tellez and McCue had arrested a man suspected of swallowing drugs. The report seemed intentionally vague, Esqueda said, and didn’t even note that Lurry had died.

Esqueda didn’t find out until later that Tellez had turned off the audio on the dashcam, but he thought it was strange that the sound suddenly stopped.

“To me, it looked like it was being tampered with,” Esqueda said. “I knew it wasn’t an accident.”

Months had passed between Lurry’s death and when Esqueda first watched the video, yet he saw no signs of an active investigation into what happened. McCue was a recruit under Esqueda’s supervision and Tellez was his training officer. Yet nobody had reported to Esqueda that a man died after one of their arrests. And none of the officers involved had been placed on leave.

Esqueda decided then to make a copy of the video, just in case something should happen to the original.

Outside his police career, Esqueda is a member of a nonprofit Star Wars club that dons elaborate costumes to walk in parades and visit children’s hospitals. He once performed in full Stormtrooper regalia at a birthday party for the police chief’s grandson. Esqueda liked to make videos of those events, so his wife had bought him a GoPro camera. He used it to record the video of Lurry’s arrest.

Two days later, a supervisor over Joliet police’s field training program confronted Esqueda to ask why the video access log showed he had twice watched the video.

Esqueda told reporters he tried to explain what had disturbed him about Lurry’s arrest, but the captain told him to shut up. He gave Esqueda clear instructions: write a short memo explaining only why he had accessed the video — without detailing its contents.

In a June 2020 memo, Esqueda wrote in just two sentences that he had heard rumors of misconduct, including by an officer he was ultimately responsible for training. He wanted to ensure that the officers involved had “conducted themselves appropriately.” The memo includes no judgment of what Esqueda saw.

He submitted the memo and took stock of the situation.

A man was dead, and video evidence suggested that Joliet officers had, at best, neglected him during a medical emergency. The public knew nothing about what happened. And a superior had instructed him to write a memo about watching the video, but gave explicit orders to omit what he’d seen.

Esqueda’s nagging suspicions about a potential cover-up overwhelmed him.

“I thought they were going to bury it,” he said.

'What do you have to hide?'

The video had, in fact, become one of Joliet’s worst kept secrets.

Less than two weeks after Esqueda made his copy, three city councilmen and Joliet Mayor Bob O’Dekirk — a former member of the local police department — sent a letter to Illinois Attorney General Kwame Raoul to request an investigation into Lurry’s death.

Meanwhile, Joliet police officials worked to get ahead of the impending controversy.

They called together a group of pastors and other Black community leaders to view the video. An attorney representing the Lurry family was not allowed to join.

According to one of the pastors present, the video police showed them did not include any sound. Instead, an officer walked them through what they were seeing, crafting a narrative of how officers employed techniques intended to save Lurry’s life.

Those pastors, including Rev. Herbert Brooks, a Will County board member, released a statement in July, calling criticism of the police unfounded.

But in a recent interview, Brooks said he and his fellow pastors were not shown the full video and they did not hear the audio. They also didn’t know Lurry’s family hadn’t been allowed to see it, he said.

The family had a right to see and hear the full, unedited material, Brooks told USA TODAY, and the omissions in the version shown to pastors now seem suspicious. “What do you have to hide?” Brooks asked of the department. “If there’s no foul play, why can’t we see it?”

More than a week after the pastors saw the video, police officials invited Lurry’s wife, Nicole, and other relatives to view it themselves. Again, there was no sound from the actual incident. Instead, the video had captions and a sergeant standing next to the screen provided the narrative about trying to save Lurry’s life.

On July 1, 2020, according to local news reports, Joliet Police officers hosted a third viewing for a group of local reporters. They weren’t allowed to make copies.

That same day, Esqueda shared his copy — which included the audio — with a local CBS news station. Esqueda appeared in an on-camera interview that aired along with the video that evening, and he criticized his fellow officers for the way they treated Lurry.

Two Internal Affairs officers showed up at Esqueda’s house to take his badge and gun. Roechner had placed him on administrative leave because he felt the leak had compromised an active investigation.

Christine M. Cole, executive director of the Boston-based Crime and Justice Institute, said that reasoning didn’t make sense.

“It feels to me this is an example of hypocrisy,” she said. “The command staff felt that they could share this video to the people they wanted to share it with but when a field officer shares it to hold his … own department into account, he’s prosecuted for it?”

The "retaliation playbook"

Esqueda said he spent part of the next four months on desk duty, but his bosses gave him no work. Meanwhile, he said his fellow officers — some that he’d known for more than two decades — shot him dirty looks or walked in the opposite direction if they saw him. Former recruits he’d trained stopped saying hello. Even secretaries stopped speaking whenever he was around.

In October 2020, investigators arrested Esqueda on official misconduct charges. They gave him the option of immediately posting bail so he wouldn’t have to go to jail. He made two fists and put his hands out in front of him, wrists up, so they could handcuff him.

“If we’re going to do this, then let’s do it,” he said.

Esqueda’s relationship with the department had already been troubled.

A month before he watched the Lurry video, Esqueda had filed an age discrimination complaint with the EEOC, claiming he was wrongly passed over for a promotion. That complaint was eventually dismissed.

Before that, May — the officer who slapped Lurry and held his nose closed — had included Esqueda’s name in an email to internal affairs that listed officers who needed remedial training. May said Esqueda had problems with decision-making, paying attention, sleeping and texting in class.

After he leaked the Lurry video, several of Esqueda's fellow officers told investigators he planned to use the video as a “Trump card” against his bosses if they fired or disciplined him in an unrelated internal investigation concerning the arrest of a woman at a July 2019 prayer vigil.

In that case, a woman filed a lawsuit against the city, Esqueda and two other officers. The lawsuit alleges that Esqueda had mocked her, calling her a "baby" when she complained after another officer tackled her and injured her knee. Her lawsuit is ongoing.

An internal affairs investigation cleared the officer who allegedly tackled the woman. But five days after Esqueda leaked the Lurry video, he received a one-day suspension on a charge of failure to supervise the officer.

Esqueda considered it absurd that he would leak the video simply to insulate himself against such a minor allegation.

“Why would I risk my freedom, my family, my pension and everything I worked hard for, for something like that?” Esqueda said of the claim.

The Fraternal Order of Police Supervisors Association is paying for Esqueda’s attorney since he’s a member, but its president, Pat Cardwell, declined to speak in support of him.

“Clearly I’m not going to,” Cardwell said. “I represent my guys. I don’t defend them.”

But he did just that for another member two years ago, calling in to a radio station to defend him against allegations he’d been drinking on the job.

Nick Beyer, who until May was a watch commander at another police department outside Chicago, said the accusations against Esqueda are part of a “retaliation playbook” departments use to discredit whistleblowers.

He should know.

Until this past May, Beyer was a 27-year veteran at the Niles Police Department, an hour north of Joliet. That's when he claims his supervisors came after him because he’d complained about fellow officers. When they found a part-time city employee passed out at a drive-thru, they drove him home without a sobriety test, said Beyer, who sued the department in August. In what he described as a cover-up, they also turned off their body cameras and didn't file paperwork.

The department put Beyer on administrative leave, demoted him and investigated him for bogus infractions, he alleged in the suit. He decided to resign rather than be fired. One of his fellow officers — a man he’d known for 20 years and considered a friend — threatened to put a bullet in his head if he told his supervisors more about the alleged cover-up, Beyer said.

The ordeal took a personal toll, he said. He started drinking wine and vodka in the mornings and was eventually hospitalized for a major depressive episode.

Shortly after going public, Beyer received a call from Esqueda, whom he did not previously know. He noted the similarities of their situations. “It’s like they have this playbook they use when they come after you," Beyer said in an interview. "No matter where you are, they do the same things.”

Cynthia Mines, who worked for the Joliet Police Department for 28 years before she retired in 2009, said her experience shows Esqueda is up against a decades-old playbook in that agency.

Because she refused to ignore fellow officers' bad behavior, Mines said, she was unfairly arrested on unwarranted obstruction charges in an incident involving several of her family members. She went to trial and was acquitted.

Mines said her problems continued when she pulled an overly-aggressive fellow officer off an arrestee, who she says was on the ground and under control. A memo from the time shows the officer was Doug May, the same officer who slapped and choked Lurry years later.

Other officers had to separate her and May, Mines said. Her complaint against him didn’t result in discipline, according to the memo. After that, she said colleagues refused to speak to her and her calls for backup were often ignored.

“You have to stand for what’s right, no matter at what cost,” Mines said. “And Javier is paying the ultimate price for that.”

Joliet does damage control

While Esqueda’s bosses branded him a criminal, they also minimized the actions of the officers in Lurry’s case.

After Esqueda leaked the video, the department posted a 27-minute edited version of it to YouTube. It is captioned to present the officers’ actions in a more favorable manner.

When May slapped Lurry, the caption ignores the fact that May said “Wake up, bitch” and simply states: “Undercover Officer slaps Mr. Lurry in the face to get his attention in an attempt to get him to comply with commands.”

Records obtained by USA TODAY show May told investigators he was aiming to clap Lurry on the shoulder or chest, and only hit his face by accident. According to the task force investigators’ report, May was allowed to review the dashcam footage before being interviewed.

By pinching Lurry’s nose and putting his hand around Lurry’s throat, May also appears to have violated a 2015 Illinois law that bans chokeholds, “or any lesser contact with the throat or neck area of another, in order to prevent the destruction of evidence by ingestion.”

The law goes on to define a chokehold as the application of "any direct pressure to the throat, windpipe, or airway of another with the intent to reduce or prevent the intake of air.”

That law was passed after the 2014 death of Eric Garner from a police chokehold in Staten Island, New York which brought increased scrutiny to the practice.

According to his own written statement, May said he intentionally tried to restrict Lurry’s breathing.

"In my experience this has been very successful in getting arrestees who are attempting to conceal narcotics in their mouth to open their mouth, due to having a hard time breathing," May wrote in a report after paramedics took Lurry to the hospital.

In the same report, May said he initially didn’t believe that Lurry was having a medical emergency and was only faking “being unresponsive.”

It was only after McCue had extracted bags of cocaine from Lurry’s mouth that May said he believed that Lurry was having a medical emergency, according to his report. But he then added that he believed that Lurry having the bags in his mouth presented a choking hazard, citing it as “another reason why” they wanted to take the drugs out of his mouth.

USA TODAY reporters showed the video of Lurry’s arrest to five law enforcement experts, who all agreed officers should have immediately taken Lurry to the hospital or called paramedics if they thought he had ingested drugs.

Chuck Rylant, a use-of-force expert with a specialty on police chokeholds, said although the case technically fits the definition of a chokehold, the ultimate factor is whether the officers were doing it to preserve evidence or to save Lurry’s life.

Both Rylant and Cole say holding someone’s nose to get them to spit something out is a decades-old technique that police are no longer taught to use.

Rylant said he was also shocked when he saw McCue put the baton in Lurry’s mouth.

“I was like ‘Oh my God, what are they doing?’” Rylant said. “That’s outside of normal policy or training protocol. I’ve never seen it.”

May’s actions during Lurry’s arrest resulted in a seven-day suspension at the end of the department’s internal affairs investigation. Tellez also received a six-day suspension after investigators determined that he had intentionally turned off the microphone, just as Esqueda had suspected.

Neither McCue, the officer who put the baton in Lurry’s mouth, nor Harrison, the officer who told him to do it, received any punishment.

Cole, also a member of the Council on Criminal Justice, said the fact that the four officers were cleared while Esqueda was charged with a felony is likely to have a chilling effect on other officers coming forward to report misconduct.

“The sergeant recognized this as inappropriate behavior and was trying to get someone to pay attention to what are probably systemic problems, and that’s laudable,” she said of Esqueda.

A future cut short

Had it not been for Esqueda, Eric Lurry’s widow said she might still be wondering what really happened to her husband.

Nicole Lurry, a graduate of Jackson State University with a degree in Biology, was working as a chemical mixer for Ecolabs in Joliet 13 years ago when she first met Eric.

They talked for hours. He had dreams of opening up his own barbershop and eventually a school for barbers. Maybe he’d run his own trucking company one day, too. She said he wanted to be his own boss and make sure his three children would never struggle financially.

“I kind of liked that,” Nicole said of Eric’s ambition. “So I wanted to be a part of that and be able to help him reach those goals.”

They had a courthouse wedding two years later. A few relatives and friends celebrated with them at Al’s Steakhouse on Jefferson Street in Joliet, then waved goodbye as the newlyweds headed for a honeymoon in downtown Chicago.

A month before his death, Nicole picked up Eric from the police station after he was arrested on a drug charge. She was angry and confused. He had just graduated from barber school and had enrolled in school to obtain his commercial driver’s license — that had been the plan, not drugs.

She said Eric turned his back when she asked him why. The only thing he told her was that he needed to provide for his family.

When Nicole saw her husband alive for the last time, he was in the intensive care unit at Amita St. Joseph’s Medical Center’s Joliet branch. He’d been stripped of his shirt and lay on a gurney. Erratic, violent spasms shook his body.

The doctors let her get close enough to touch him. She ran her palm up and down her husband’s forearm. Patted his chest. Rubbed his stomach. Told him it would be okay.

The doctor explained it was bad. He’d never seen someone in this condition survive.

At 2 a.m. there was a code blue. Hospital records show they tried to revive Eric for 22 minutes before Nicole finally told them they could stop.

Tears streaming down her face, Nicole sat and waited for the medical examiner to collect her husband’s body.

Later that evening, a Joliet Police sergeant informed reporters Lurry had died of an apparent drug overdose. Most details of his encounter with police were omitted.

A month later, Nicole found out she was pregnant with twin boys who would have been her and Eric’s only children together.

“It was bittersweet,” she said.

She said she tried every day to keep her stress level down, even as she fought to get answers about what happened. But a week after she viewed the video of her husband’s arrest, she had a miscarriage. The ashes of her unborn sons sit in an ombre blue urn encased in silver metal leaves on top of her fireplace, opposite a smiling photo of her and Eric.

Below the surface

Nicole Lurry’s wrongful death lawsuit against Joliet Police is ongoing. Michael Bersani, the lead attorney in the case from the firm hired to defend the city and the four officers against the lawsuit, said in an interview last week that the amount of drugs reported in Lurry’s system after his death prove that he died of self-induced overdose.

“He’s the one who put the drugs in his mouth,” Bersani said. “The city’s position is that his death had nothing to do with what the officers did or didn’t do.”

The criminal case against Esqueda could go to trial in January, and the postponement of his final internal discipline hearing leaves that part of his case undone as well.

Roechner, the ex-chief who initially disciplined Esqueda, said there’s more to Esqueda’s story than the public knows.

“I agree 100 percent with people coming forward,” Roechner said, “but people need to have all the facts before they jump to conclusions.”

Esqueda’s case is unfolding as parts of the nation are passing police reform legislation. In Illinois, several of those provisions aim to protect whistleblowers and punish those who retaliate against them.

Among the new laws is a rule that officers have a duty to intervene when they witness other officers committing brutality or other misconduct. Another law allows for police officers to lose their certifications if they are found to have retaliated against another officer.

“Good officers despise bad officers,” said Elgin Sims, the Illinois State Senator who authored the reform bill. “When you believe in duty and honor and protecting the community, you shouldn’t have to worry about no one showing up to help you if you’re on a call and you’ve blown the whistle on a bad officer.”

Sims said he didn’t know the specifics of Esqueda’s case but that he hoped prosecutors would resolve it “in a way that assures the public that the system will protect them."

Illinois Attorney General Kwame Raoul said he was aware of Esqueda's case but couldn’t discuss any details.

Speaking generally, Raoul acknowledged that whistleblowers can sometimes feel scared to report misconduct internally but believes it’s difficult for leaders in his state’s police agencies to fix issues in their departments without officers willing to talk to them.

“I can appreciate the process and procedures,” he said. “At the same time, I think it’s important to not to take a posture that would suggest that anyone is being punished for whistleblowing.”

Esqueda believes that is exactly what is happening to him, while the officers he crossed the line to expose have not paid nearly the same toll.

“Every time I think about that video I get choked up,” Esqueda said of Lurry. “I was taught that when people are in our custody, they’re in our care, we are the caretakers. You don’t treat a man that way, you know. He was a human being.”

As he has from the first time he counted the seconds on the video, Esqueda goes to his backyard pool sometimes and disappears below the surface. He tries to see if he can hold his own breath for one minute, 38 seconds.

He never can.

Daphne Duret, Brett Murphy and Gina Barton are reporters on USA TODAY's investigative team.

Daphne Duret is a 2021-22 Knight-Wallace Reporting Fellow at the University of Michigan. Contact Daphne at dduret@gannett.com, @dd_writes, by signal at 772-486-5562. Contact Brett at brett.murphy@usatoday.com, @brettMmurphy, by Signal at 508-523-5195. Contact Gina at gbarton@gannett.com, @writerbarton.

This article originally appeared on USA TODAY: Illinois cop exposed police misconduct. Then he was arrested for it.