My Take: A political asteroid hit Earth in 1517. Another is headed our way

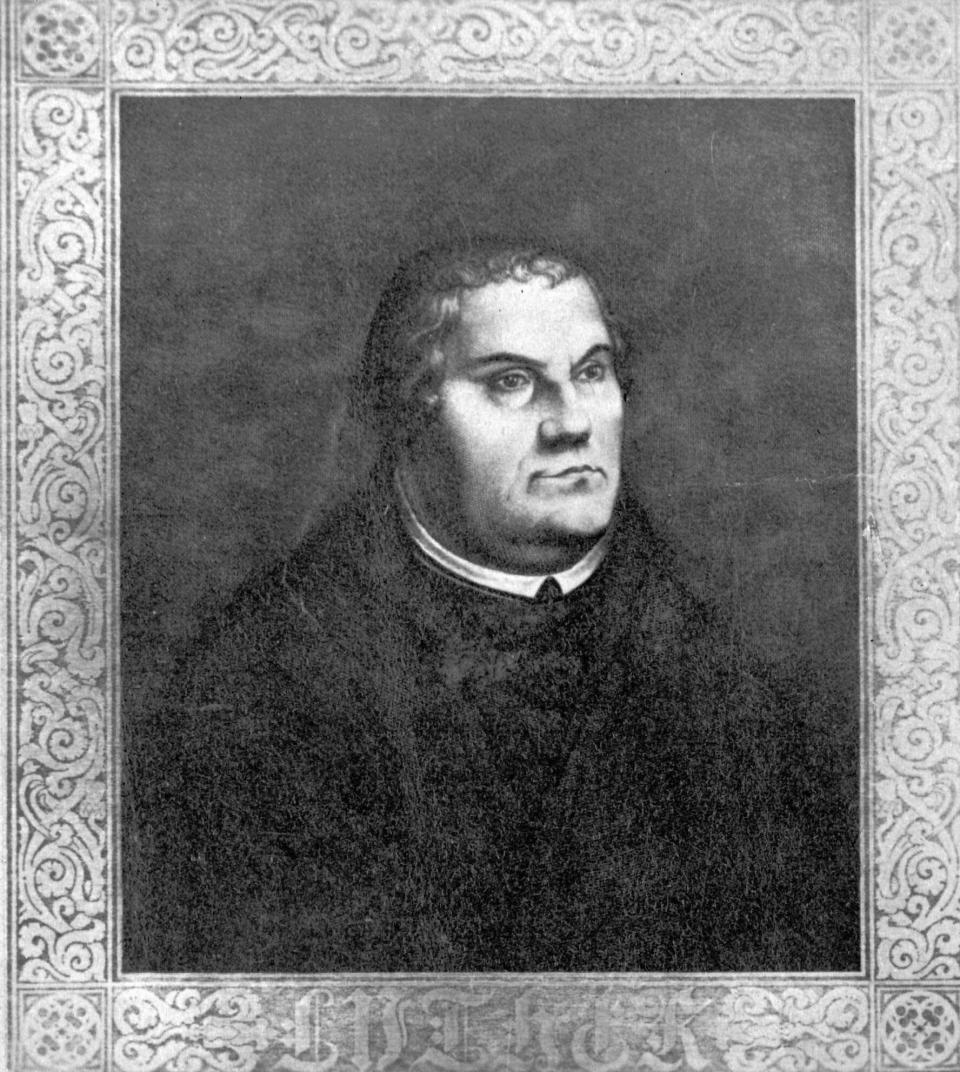

It seems strange that an issue about religion posted on an early “facebook” platform, the door of a church, changed not only the faith of the Western world, but the form of its governments, the way of its economic life, and the strength of its science. That is what happened in 1517 when Martin Luther raised concerns about his own Catholic Church.

There had been about 1,000 years of general conformity to the Catholic way of life in Europe, so why did things change now? Luther’s complaint took fire only now because European countries were benefiting from a renaissance in ancient literature translated into their own languages, like the New Testament scripture, and the invention of the printing press in the mid-1400s. Many now agreed with Luther that a variety of practices of the church were un-biblical.

In the first place, the church had grown to be very opulent, mimicking the royal dynasties of the greatest nations, able with its money to build great cathedrals and even hire armies to do its bidding. But the people felt the sting of its fund-raising practices, which included the sale of indulgences, or waivers from time spent after death in purgatory, and even sale to the wealthy of waivers from penance for sin. The new churches became less focused on wealth and more on simpler forms of worship, like that of Jesus.

The new churches also cut down the number of sacraments requiring the administration of priests for such things as confession, with accompanying penance regimes and absolution/forgiveness. They didn’t see enough Biblical justification for seven sacraments.

They also decided they could administer their new denominations closer to their own congregations rather than from a central location like Rome. Finally, they addressed a number of the doctrines they felt were out of line with scripture, like the doctrine of the godhead, which positioned Jesus as one and the same as the ancient God of heaven.

When the new churches made the “discipline” or administration of their faith denominations more democratic, they saw no reason why their civil governments could not also be more democratic. After all, the papal system of autocratic/aristocratic administration of the church scratched the backs of the monarchies of Europe, and the kings in turn supported central administration of the church. Perhaps now the power of religion and politics could be located more locally so people could decide things for themselves. The Bible seemed to support such localism.

When several new branches of the Christian faith split off from the trunk of the church, they also formed political parties. Some argued, for example in England, for several powers to be shifted from the monarchy to parliament. Other branches, more democratic yet, argued for overthrowing the monarchy altogether and placing all power in the hands of a representative parliament, which England did for a time in the 1600s.

Still other branches, like the Puritans, wanted to administer their churches in their own congregations, calling ministers and even deciding the range of acceptable doctrine among their own local members. They also wanted freedom to do civil government locally as well. This last group England agreed to allow to immigrate to America, giving them full governmental autonomy in return for claiming land for their native country.

The economic system of the new Protestant churches necessarily followed the degree of freedom in their political administration. Ownership of land, incorporation of businesses, creditor/debtor relations, and inheritance laws all were freed-up from restrictions placed upon them by monarchy. This occasioned a tremendous burst of energy well known in early America as the Protestant work ethic.

More: My Take: Can America change its course?

More: My Take: America’s Dark Ages have arrived

More: My Take: America is reliving British history

Freedom of thought in religion and politics also led to freedom of thought in science at the universities. Consequently, the century of the 1600s became known as the period of the Scientific Revolution. Free enterprise and free science led to America’s emergence as the greatest economic power on the globe.

One might ask why it was that the church was the original site of all this revolutionary fervor, rather than the government? The reason is that from the time of ancient history, religion was the driving force of nations because it was the champion of science and the keeper of history. Ancient people wanted to decipher the mysteries of the heavens and of the earth. In virtually every ancient nation there was a two-part approach to doing this which most everybody accepted. The first was through observation and study/calculation. The second was through hospitality extended to the unseen heavenly powers by means of offerings of food (sacrifices) and temporary housing in man-made temples to accommodate their visits to earth. This second approach predominated in the ancient world.

Every nation had two kinds of leaders in government, one the practical one who could schmooze with the people to gain their approval and lead their battles, and the other the brains of the government operation, who focused on science, law, history, and sacrifices to the heavenly gods so as to free up revelation of their secrets, their intentions, and their favors. The first was called the chief magistrate, king, or judge of the nation, and the second was called the vizier, prime minister, high priest, or oracle of the nation.

Throughout history the chief magistrate and the high priest jockeyed for supremacy in the eyes of the people. When the Roman empire fell, the high priest of the Catholic Church was able to achieve supremacy over the fragmented governments of Europe. Over time, however, the church abused its power. The Protestant Reformation learned the bitter lesson that too much central power corrupts both church and state. Henceforth they separated the secular and sacral powers, and decentralized both.

Because human beings were discovering so many of the mysteries of the heavens, the earth, and of the human body, the government and the people in modern times took over much of the function of science, government, history, economics, education and law that the church and its spiritual specialists had monopolized for so long. This left the church with a focus on ethics, the law of families, government of the Sabbath day, health care/healing, and relations with the unseen powers of heaven.

Today, after 500 years of decentralization in the powers of nations, economies and churches, the trend has turned markedly back toward centralization of political and church power, and monopolization of economic power. Conditions have become ripe for another Reformation of life in the Western world. This likely can only happen with a revolution in understanding of history, law, and science, as before. The powers of curiosity and knowledge have to challenge the powers of brute force for supremacy.

— Robert Kimball Shinkoskey is a public health worker and historian of democracy.

This article originally appeared on The Petoskey News-Review: My Take: A political asteroid hit Earth in 1517. Another is headed our way