‘Political guerrilla warfare’: The Iowa caucus legend grows as Jimmy Carter cements a presidential playbook

- Oops!Something went wrong.Please try again later.

- Oops!Something went wrong.Please try again later.

This is the second installment of a three-part story. Read from the beginning here.

8 p.m., caucus night 2020: A muddled presidential field awaits clarity

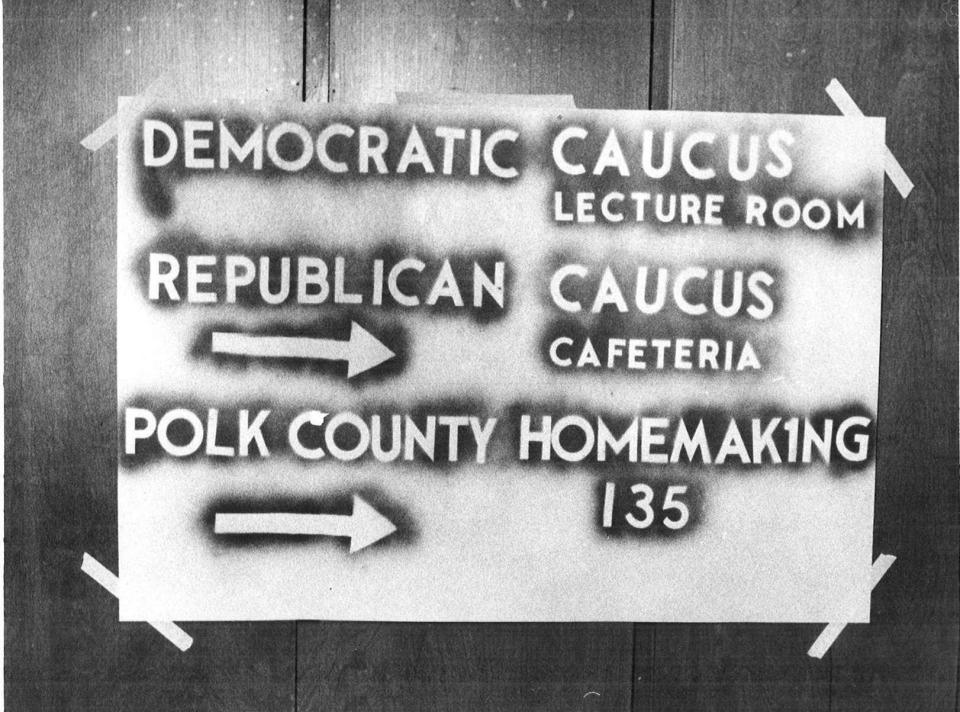

Across the state, the vast majority of caucuses — nearly 1,700 of them — are coming to a close and Iowans are soaking up the glow of the international spotlight. Most precinct sites are at large community centers or school auditoriums, their masses having outgrown the pastoral barns or charming living rooms of previous years.

In the last three days alone, presidential candidates and their surrogates have made 75 separate appearances, crisscrossing Iowa from river to river. In final, desperate bids for support, they take no chances, leave nothing behind.

Outside the Iowa Democratic Party’s Caucus Day headquarters at the Iowa Events Center in Des Moines, Chairman Troy Price takes it all in. Smoking a cigarette, he feels confident. His team has assured him that things are going well. They are prepared for nearly any disaster scenario.

Raised in Durant, a small town in eastern Iowa, Price is a longtime Democrat with an impressive resume he’s built campaign by campaign since graduating from the University of Iowa in 2004. He’s an Iowa caucus insider, too, having played major roles in President Barack Obama’s reelection campaign and Hillary Clinton’s 2016 presidential run.

And tonight, he’s in charge of ensuring the smooth operation of the 2020 caucuses, one of the most influential political events of the election cycle.

He heads back inside toward the suite of rooms the party has commandeered for the evening at the sprawling two-building conference center, just a few blocks from the city's center.

There is a boiler room set aside for volunteers taking phone calls. Another room is set up nearby for campaigns. A strategy room acts as a command center for party communications. And Price has a green room on the mezzanine.

Few people have access to more than one room.

Following the muted movie theater carpet to his green room, Price sees a staffer walking toward the media center to deliver the first batch of results, another sign the earliest gatherings are successful.

A new reporting app created for precinct captains to relay results quickly has led local party leaders to promise results within the hour, and it seems they are right on time.

But 15 minutes goes by, and cable news doesn’t have any new headlines.

He opens his door to investigate but is ushered back in by the tech gurus who have been working on the app. They kick everyone else out before giving Price the news.

The numbers are spitting out wrong, they say.

“’We can see the numbers on the back end that are going into it. The numbers are good,’” Price remembers them saying. “But then they're getting switched. The numbers are coming up differently once they're going up into the public-facing reporting system.”

Imagine a couple of wires getting crossed as they go from the data warehouse to the public-facing system, they say.

They think they just need to uncross the wires and then everything will be OK.

Just 10 minutes, they say.

More than 2,600 journalists have set up shop in a slick downtown Des Moines filing center — a 1,000-person increase from 2016 — where they wait to transmit across the globe the results of all that buildup.

And what those results will say is far from certain.

The presidential field sits in a confused muddle. Four candidates have jostled for months in polling as caucus favorites, but none has yet broken out of the large pack of contenders.

Former Vice President Joe Biden and U.S. Sen. Bernie Sanders entered the race as giants — well-known figures who towered over their lesser-known competitors in the polls. U.S. Sen. Elizabeth Warren, a progressive darling with a down-home biography, has ridden a surge of support in the fall.

And then there is Pete Buttigieg, the small-town Indiana mayor whose first appearance in Iowa at an Ames coffee shop had been attended by little more than a dozen people — his words mostly drowned out by the grinding of coffee beans and the whistle of milk steamers.

After a few well-handled national TV appearances, polling showed he had quickly surged into the top tier of contenders in Iowa. Buttigieg drew his first 1,000-person crowd at a spring outdoor rally in Des Moines, where Iowans chanted “boot-edge-edge” as young, energetic staffers lifted signs above their heads.

Now, he’s in contention to win it all. Awaiting results in a nearby hotel room as his rally at Drake University kicks off, the former mayor hopes his ground game — a playbook created by George McGovern but cemented by Jimmy Carter four years later — will propel him through the next three early states, Super Tuesday and, eventually, to the White House.

That he is even a contender speaks to his meteoric rise. It’s the kind of rise that long-shot candidates hope for, the vision they travel to Iowa to manifest. It’s the kind of story that for five decades has explained and rationalized Iowa’s improbable role as the nation’s earliest adjudicator of presidential elections.

And now, his legacy, his path to the presidency — all of it hangs on the outcome of the Iowa caucuses.

The 1976 rise of ‘Jimmy who?' How the Iowa caucus legend is born

Political consultant Tim Kraft’s job in 1975 was to turn “Jimmy who?” into Jimmy Carter, the bona fide presidential contender. This was a tall order for a first-term Georgia governor, who was almost entirely unknown outside his home state, had no money and boasted just a tiny campaign infrastructure.

But Kraft had read Gary Hart’s account of George McGovern’s 1972 Iowa caucus run and studied their moves. Results be damned, he’d seen what headlines had done for that long-shot candidacy, how Iowa had given an unknown entity enough momentum to take on party favorites.

That could be Carter, too, couldn’t it?

Iowa Democratic Party Chair Tom Whitney had also watched the unlikely rise of McGovern, how his surprise “exceeding expectations” had made Iowa — a state far from coastal population centers — seem prescient in the aftermath of the primary cycle.

National attention could help Iowa Democrats generate contributions and new voters, Whitney figured. So when he took over in 1973, he began to drum up publicity for the newly minted first-in-the-nation contest by casting the state as candidates' preeminent proving ground. Would-be presidents could come here to make their case directly to the people and be rewarded for it.

"We organized a very, very significant kind of effort to convince first the candidates that they ought to be in Iowa because the national press was going to be here, and then to convince the national press that they should be in Iowa because the candidates were going to be here,” he said in a 2007 interview with Iowa Public Television.

Politicians needed the media, and the media needed a story. Whitney’s caucuses were happy to play backdrop to both. The symbiotic relationship that would come to define the way America picks presidents was born.

The first test of this new partnership came in October 1975 at the Iowa Democratic Party’s Jefferson Jackson Dinner, a statewide event with all the political theater of a national convention.

Building on the hype, the Des Moines Register announced it would hold a straw poll to gauge support for each presidential contender a few months ahead of the actual caucus. But the Register would count the votes only of those who paid $25 for a boxed chicken dinner and a seat on the floor. Everyone else could pay $2 to watch from the sidelines.

Devoted Carter supporters were wary of the steeper price but wanted to be counted.

“To me,” Kraft said in a written account of the campaign, it was “an open invitation to infiltrate.”

The campaign organized volunteers to flood the event, suggesting that they might want to buy the $2 tickets and casually work their way to the floor to secure a ballot.

A campaign supporter reserved a section of seats inside the auditorium — front row — where they’d be on full display for the media. Somebody else found boxes of straw hats and affixed Carter bumper stickers to their brims, ensuring their allegiance was obvious to the cameras.

“It was political guerrilla warfare at its best,” Kraft said in an interview, recalling the night fondly.

Carter handily won the straw poll and, more importantly, the battle for visibility.

The result “was rocket fuel” to the campaign, Kraft would later say in a speech, and it put Carter on the national map.

Or, at least, in the pages of The New York Times.

“Carter Appears to Hold a Solid Lead in Iowa as the Campaign’s First Test Approaches,” the headline read over legendary political reporter R.W. Apple Jr.’s writeup.

Carter and his campaign had taken what McGovern learned to a new level. Now, all he had to do was deliver a surprise on caucus night.

For his part, Whitney was looking for that sort of attention, too — any sort of storyline that would put Iowa’s caucuses in the evening news’s A block.

Indeed, when caucus night finally came around, everyone who was anyone in American political journalism flocked to Des Moines to cover the Iowa caucuses — all of them aware that during the last go-around, Iowa had foretold a change in the political winds. This time, nobody wanted to be left in the dust.

Ready to prove that Iowa had become the political destination he’d envisioned, Whitney eagerly awaited the results as they trickled in, preparing to unveil them to the assembled throngs. He’d even offered Iowans the chance to watch the media at work for $10 a head, a ticket that came with a front-row seat to history and two drinks.

The entire political world seemed to ache for clear, measurable data — anything empirical that would make sense of the field.

But with 85% of precincts reporting, the delegate count was far from impressive, according to a Wall Street Journal account. Jimmy Carter had won eight delegates — well short of the 39 delegates awarded to “uncommitted.” None of the other candidates had enough support to claim any delegates at all.

This was not the clear, politically prescient result Whitney wanted to sell to the media.

But what if those weren’t the results?

After surveying the party’s statistician and a few trusted confidants, Whitney came up with a plan to ignore the party's rule that a candidate must win at least 15% support to collect any delegates — a rule designed to weed out weaker candidates and help Iowa Democrats build consensus, according to the Journal.

Even with this new math, uncommitted came out on top with 18 delegates. But the gap had closed between “no one” and Carter, who was awarded 13. And some of the other candidates — Birch Bayh, Fred Harris, Morris Udall and Sargent Shriver — picked up a handful of delegates, enough to make it seem like a race.

Days later, the Register highlighted Whitney’s sleight of hand. “The projections by the state party added an element of certainty that simply doesn’t exist,” political reporter James Flansburg wrote in the Sunday paper.

But it didn’t matter. The narrative had taken hold: Carter had “won” in Iowa.

The momentum of the political machine shifted, giving him weight and credibility as he competed in later states and famously propelling him to the Democratic nomination and then the presidency.

The blueprint for every long-shot candidate who followed was written. There was no looking back.

For better or worse, Iowa’s caucuses wouldn’t be just a measure of political reality.

They would create political reality.

In Iowa’s ‘fair playing field,’ candidates look for the 'springboard' effect

No politician arrives in Iowa by accident.

In the months before U.S. Sen. Cory Booker announced as a 2020 presidential candidate, he had intentionally stayed away from the state to avoid stoking the speculation that already buzzed around his potential presidential bid.

“Recently I was in Nebraska, Kansas, Illinois and Missouri, so in farm country,” Booker said in a September 2018 interview with the Register. “In fact, we were very close to the Iowa border, and my chief of staff gave me firm instructions not to cross the border or else you would speculate about me.”

Reporters love to speculate. Especially in Iowa.

Most politicians play coy about their true intentions when they come to town, even off the record. They got invited to speak at this local party dinner or that party fundraiser, or they’re here to help their very-dear-but-very-distant friend win an obscure special election.

The caucuses? Sorry, never heard of ‘em.

Local reporters, sitting at coffee shops that sometimes feel more like high school cafeterias, try to tease out their plans regardless.

The Register ran its first story about the 2020 Iowa caucuses in July of 2016, when the National Governors Association held its annual meeting in Des Moines and local politicos started speculating which of the attendees — Indiana Gov. Mike Pence, Wisconsin Gov. Scott Walker, Colorado Gov. John Hickenlooper and Virginia Gov. Terry McAuliffe among them — might be harboring future political ambitions in the state.

“Iowans never take off their campaign goggles,” then-Republican strategist Tim Albrecht said at the time.

The long shots tend to adhere to the Jimmy Carter “arrive early and campaign often” strategy, announcing their candidacies as early as possible. John Delaney, a U.S. representative from Maryland, announced his 2020 bid in the summer of 2017, arriving in the state with a generic, white-guy-congressman pitch backed by his own personal wealth. Andrew Yang, an offbeat entrepreneur from California, never really seemed to announce his candidacy. Few had heard of him until he sort of showed up in Iowa one day in 2018 and started campaigning.

The serious contenders began sending representatives to quietly recruit staff in Iowa that winter. Warren became the first A-list candidate to form an exploratory committee and launched a two-day, four-stop campaign swing across Iowa in January 2019 — an event that the media deemed to be the formal launch of the caucus season.

That spring, all the major television networks sent their embeds to live in Iowa — a crop of 20-something reporters willing to do the thankless, grueling grunt work of chasing candidates across the state with their bulky cameras in tow.

For most candidates, the game of the Iowa caucus is to make moves with a single-pointed focus on the “springboard” effect. It’s really the only prize Iowa has to offer. With a measly 49 delegates to the national convention and six Electoral College votes, Iowa is dwarfed in size and influence in other respects by more populous states.

But as is often said: Iowa isn’t first because it’s important. It’s important because it’s first.

For the caucus machine — the entire ecosystem of businesses and consultants and staffers and journalists that feeds off the quadrennial nominating process — being “First” means personal phone calls from candidates and White House invitations from eventual presidents. “First” means jobs in the administration and appointments to ambassadorships. “First” means fundraising support and endorsements for state and local candidates.

More than anything tangible, “First” is about status. It elevates Iowans who would otherwise toil in political obscurity and confers import on their every thought and action.

Without “First,” Iowa blends back into what is perceived to be the homogenous mass of the flyover Midwest so often overlooked by those on the coasts. Reporters at CNN and The New York Times do not keep Iowans on speed dial without “First.”

Even the difference between first and second — just a matter of days on the political calendar — is a chasm in terms of access and influence. The field of 2020 Democratic contenders held 920 events across New Hampshire, which holds the nation’s first primary about a week after Iowa’s caucuses.

Candidates nearly tripled that in Iowa, making close to 3,000 separate appearances.

For those willing to put in the time on the campaign trail, Iowa is “as close as you can get to a fair playing field,” said Addisu Demissie, Booker’s 2020 presidential campaign manager.

Money is not a barrier to entry here. Lesser-known candidates can compete with the big dogs in Iowa from Day 1.

The state itself is relatively small: 3.2 million people spread across 56,000 square miles — you can drive from border to border in fewer than five hours, no private jets required. The cost of television advertising is minuscule compared to states like Michigan with its expensive Detroit media market. Candidates compete by hopping in a car, weaving through backroads, meeting people along the way and earning their votes with handshakes.

And Iowans themselves are different. Iowans can be fickle and hard to pin down, even when candidates court them. They ask questions directly to candidates with the expectation that they are answered.

“There's something really, really special about the Iowa caucuses,” said Lis Smith, senior adviser to Buttigieg’s 2020 campaign. “It's one of the most beautiful things in American politics, because, in Iowa, any normal person, any normal voter can go and hold some of the most powerful people's feet to the fire.”

“They can cut through the b.s. that other politicians can get away with in bigger states where they're just running ads.”

And, most importantly, Iowans believe in hearing out every candidate in person before making a choice — long shot or not.

“Joe freaking Sestak had people in front of him. Richard Ojeda had people in front of him,” Sue Dvorsky, former Iowa Democratic Party chairwoman, once said of the long-shot Democratic presidential contenders. “There was never a time when they were in an empty room.”

9 p.m., caucus night: A results-hungry media revolts

The boiler room is an endless cacophony of piercing rings and clanking phones.

Incoming calls have reached an avalanche, with some on hold an hour or longer. The chaos moves out into the public eye as journalists and others wait on results that aren't coming.

"One call would be someone screaming at me that CNN was screaming about the results," says a call room volunteer in an interview a few days later. "And then the next call would be somebody actually calling in the results. Or journalists were phone banking the phone bank. So we couldn’t talk to precinct captains because CNN was having their entire staff f---ing phone bank us."

On cable news channels in particular, the demand for results reaches a frenzy. Lacking numbers, panelists are left to speculate wildly, and analysts have nothing to tap at on their dynamic touchscreens. It is, without question, bad TV.

Shawn Sebastian, a caucus precinct leader in Story County, is live on CNN with Wolf Blitzer as he simultaneously waits on hold with the call center. He says he’d been on hold for more than an hour as he waited to report results.

He is still live when someone from the call center finally connects and, apparently impatient for him to transfer over, hangs up on him.

“They hung up on me,” Sebastian tells Blitzer, letting out a short laugh of frustration and disbelief. “They hung up on me.”

CNN's Chris Cuomo soon calls the evening an “epic failure,” proclaiming that regardless of when the results come in, “they’re going to be questioned in terms of their authenticity.”

“Literally, this state had one job. They had one job,” he says, looking directly into the camera. “And they blew it at the most important time in the election. The criticism should not be mitigated by any means.”

As the incoming calls begin to slow, volunteers are put to work making outgoing calls to try to track down missing data from precincts that have not yet reported their results.

Democrats in the room divvy up assignments based on where they have personal connections and begin dialing local elected officials, friends and county chairs, asking for the results. Other times, they ask those friends to knock on the doors of precinct leaders who still owe the party data.

Volunteers quickly discover that they are competing with members of the media, who, without official results, have started calling county chairs directly for information.

In his green room, Price and his team keep waiting. Every 10 minutes, they’re told to hang on another 10 minutes. Then another.

"The integrity of the results is paramount," reads a statement from the Iowa Democratic Party, issued close to 10 p.m., explaining the data’s “inconsistencies.” "We have experienced a delay in the results due to quality checks and the fact that the IDP is reporting out three data sets for the first time. What we know right now is that around 25% of precincts have reported, and early data indicates turnout is on pace for 2016."

About 20 minutes later, a call goes out to Iowa Democrats, frantically seeking extra volunteers for the boiler room.

They have to get this under control.

This article originally appeared on USA TODAY: How the Iowa caucus became essential for presidential candidates