Pompeo dismisses Afghan rejection of key clause in US-Taliban deal

Mike Pompeo, the secretary of state, on Sunday brushed off the Afghan president’s rejection of a key clause of the US-Taliban deal he saw signed into effect on Saturday.

Related: US and Taliban sign deal to withdraw American troops from Afghanistan

After Ashraf Ghani rejected a Taliban demand for the release of 5,000 prisoners which was included in the deal as a condition for further talks, Pompeo was asked if a major stumbling block had emerged only a day after the deal was signed.

He told CBS’s Face the Nation: “There have been prisoner releases from both sides before. We’ve managed to figure our path forward.”

Pompeo said the deal signed in Doha on Saturday, which will lead to US troop withdrawals, was historic and contained detailed commitments by the Taliban to reduce violence. He also expressed hope that talks would begin in the coming days between Afghanistan’s government and the Taliban, adding that Donald Trump would be actively engaged.

Pompeo gave no date for a Trump meeting with Taliban leaders, which the president promised at the White House on Saturday.

The deal faces criticism at home but in Kabul, Ghani told reporters: “The government of Afghanistan has made no commitment to free 5,000 Taliban prisoners.”

Under the accord, the US and the Taliban are committed to work expeditiously to release combat and political prisoners as a confidence-building measure, with the coordination and approval of all sides. The agreement calls for up to 5,000 Taliban prisoners to be released in exchange for up to 1,000 Afghan government captives by 10 March.

Ghani said it was “not in the authority of United States to decide” about the swap, because it was “only a facilitator”.

Speaking to CNN, the Afghan president said Trump had not asked for the release of the prisoners and the issue should be discussed as part of a comprehensive peace deal.

“The political consensus … that would be needed for such a major step does not exist today,” he said.

Ghani said key issues need to be discussed first, including the Taliban’s ties with Pakistan and other countries that had offered it sanctuary, its ties with what he called terrorist groups and drug cartels, and the place of Afghan security forces and its civil administration.

“The people of Afghanistan need to believe that we’ve gone from war to peace, and not that the agreement will be either a Trojan horse or the beginning of a much worse phase of conflict,” he said.

Pompeo said that though the Taliban “have an enormous amount of American blood on their hands”, they “have now made the break. They’ve said they will not permit terror to be thrust upon anyone, including the United States, from Afghanistan.”

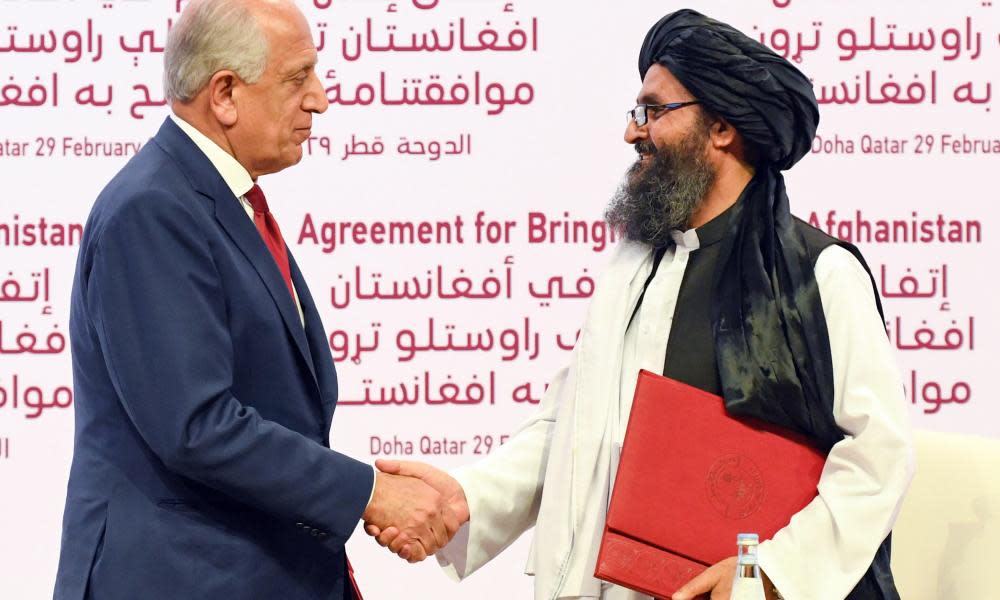

Saturday’s accord was signed in Doha by US special envoy Zalmay Khalilzad and Taliban political chief Mullah Abdul Ghani Baradar, witnessed by Pompeo. Pompeo said he met “a senior Taliban negotiator”. Baradar met foreign ministers from Norway, Turkey and Uzbekistan and diplomats from Russia, Indonesia and other nations.

“The dignitaries who met Mullah Baradar expressed their commitments towards Afghanistan’s reconstruction and development … the US-Taliban agreement is historical,” said Taliban spokesman Zabiullah Mujahid.

In the US, Republicans in Congress expressed concerns about the logistics of the deal and trusting the Taliban, while Democrats demanded congressional involvement. In a Saturday briefing at the White House, Trump rejected all criticism and said he would meet Taliban leaders.

Aides to Ghani said Trump’s decision to meet the Taliban could pose a challenge to Afghanistan’s government at a time when the US troop withdrawal is imminent.

Washington is committed to reducing troops to 8,600 from 13,000 within 135 days of signing the deal. The US is also committed to work with allies to reduce the number of coalition forces, if the Taliban adheres to security guarantees and ceasefire. If so, a full withdrawal of all US and coalition forces will occur within 14 months.

The Taliban ruled Afghanistan from 1996 to 2001 and imposed draconian restrictions on women’s rights and activities it deemed un-Islamic. After being ousted in a US-led invasion following the 9/11 attacks engineered by al-Qaida forces harboured by the Taliban, the Taliban led a long and violent insurgency.

Related: Trump ally Graham and ex-aide Bolton voice concerns over Taliban deal

“The Bush administration and the Obama administration both tried to get the words that were on the paper yesterday that the Taliban would break from al-Qaida publicly,” Pompeo said. “We got that. That’s important. Now, time will tell if they’ll live up to that commitment is our expectation. They have promised us they will do so and we’ll be able to see on the ground everything they do or choose not to do.”

The Afghan war, easily America’s longest, has been a stalemate for more than 18 years. More than 2,400 Americans have been killed and more than 20,000 wounded. As of October 2019, more than 43,000 civilians are estimated to have been killed.

Talks between Afghan government and Taliban groups will be “rocky and bumpy”, Pompeo said.

“No one is under any false illusion that this won’t be a difficult conversation. But that conversation for the first time in almost two decades will be among the Afghan people.”