In the poorest hills of Nepal, getting more than I could ever give

PALUNG, Nepal — You can get fixated and overwhelmed by the poverty and challenges of life in Nepal, but there is a certain poetry to it all if you stop long enough to listen and look. The birds sing the sun up while the ubiquitous feral dogs collapse in the dust to sleep off a long night of barking and fighting (mostly under my window). The children trickle down from the surrounding hills into the schoolyard in their uniforms, their arms linked or draped around each others’ shoulders as they do everywhere they go.

High in the hillsides, where terraces have been carved like giant staircases, the women work in the fields, dressed in their brightly colored saris, dashes of crimson, blue and marigold against the green canvas of the hills, their hair combed and neatly bound, their bare feet caked with dark earth.

This is my mental photo album now that I am ensconced again at home in this American life, where there is so much comfort and ease that there is time to squabble over the use of pronouns in the din of American entitlement. My mind wanders back to the hard-scrabble existence of Nepal, where it is enough just to exist day to day, at a slow pace not even our children know anymore.

But I should digress. I should pause to tell you how I got here. What would possess someone to pay thousands of dollars to take a mind-numbingly long flight to the other side of the world, endure a stomach-tossing bus ride on mountain roads the size of golf cart paths, sleep on the floor of a schoolhouse, use a bucket of (cold) water to both shower and flush a hole-in-the-ground toilet (not at the same time), and perform manual labor for a few days?

That’s what I wondered when I found myself in the backcountry of Nepal in the summer of 2022 with 20 other volunteers from a wide variety of backgrounds — a former contractor, a schoolteacher, a carpenter, a former Navy helicopter pilot, a yoga instructor, doctors and nurses, a former ironworker, teenage students, and a department store manager, most of them from Utah, others from Virginia, California, France and Spain — to perform humanitarian work.

They could’ve been sitting on the beach in Hanalei; they chose this place instead. They signed up for an expedition with Choice Humanitarian, a 40-year-old, Utah-based nonprofit that partners with communities in eight third-world countries to help lift them out of poverty — Bolivia, Guatemala, Ecuador, Peru, Mexico, Kenya, Nepal and Navajo Nation. Among other things, they take volunteers on “expeditions” to perform service in those communities.

We signed up for Nepal, specifically to work in a small mountain village called Palung. We got our first glimpse of Nepali life shortly after landing in Kathmandu, where the streets are a high-speed collage of roaming monkeys and dogs and street vendors and dilapidated metal shacks and shops and piles of old earthquake rubble and garbage-strewn rivers the color of cocoa and steaming piles of trash on the roadside and traffic that moves like two large opposing rivers colliding but without so much as a fender bender. Nepal is so out of step with the rest of the world that the time difference between it and Utah is an odd 11 hours and 45 minutes.

Some of the veterans in the group, seeing my bewilderment, assured me that our time in the village would be life-changing — for the better, I mean. Jen Hatch, the grade-school teacher from Virginia who would be the pied piper of the village school yard in the week ahead, has made numerous such trips. Marc Johnson, an energetic, adventurous doctor from Ogden, has done a half-dozen of them. Chuck Mercier, a funny, wise-cracking cynic with a soft side who moved from Park City to Spain with his wife and children, has made two trips to Nepal and one to Kenya.

“If you don’t even lift a shovel while you’re here, if you don’t do anything but talk to the villagers, it’s mission accomplished,” Mercier told me. “For you to take time and spend money and leave your family and work with them, yeah, it’s a big deal to them. You’re in for an amazing experience. We think we are helping them, but a lot of times you feel like they helped you.”

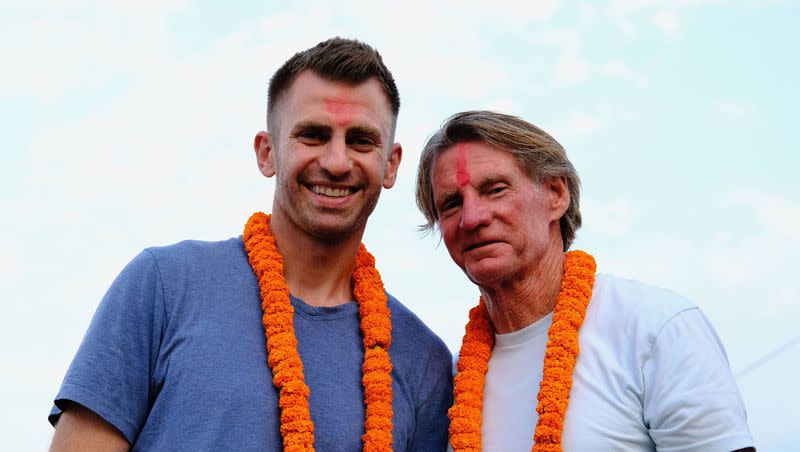

Shortly after the death of my wife in the fall of 2019, my oldest son Preston suggested that we take the Choice expedition to Nepal to get away, lick our wounds and spend time together. Our trip was postponed 21⁄2 years by the pandemic. We finally undertook the long journey at the end of May — a 16-hour flight to Doha, followed by a five-hour flight to Kathmandu, then the five-hour rollercoaster bus ride on mountain roads so narrow that drivers honk at each of the hundreds of blind turns to warn cars headed our way.

And there it was: Palung, an isolated village of 8,000 people spread over a green valley and the surrounding hills. The people, who had been waiting for hours we were told, welcomed us like the Marines marching into Paris. They placed necklaces of marigolds around our necks and paraded us through a gauntlet of smiling, cheering people accompanied by music and drums until we arrived at a grandstand where there was more music, dancing and speeches.

“Namaste,” they said to their guests. It is their traditional greeting, made with hands pressed together under their chins in an attitude of prayer. It is a greeting, a sign of respect (and far superior to the West’s handshake, fist bump and high-five).

Our reaction was best described by Magdalena Gladstone, a kind, gentle French woman in our group: “They were so humble and welcoming; my heart burst open.”

We spent a couple of days building the foundation of a new school. We filled the holes — which had been dug earlier — with a layer of rocks, at one point forming a line and passing the rocks from person to person like a fire brigade. We spent one entire day mixing concrete and loading it into wheelbarrows to pour over the rocks at the bottom of the foundation.

One morning we hiked over a suspension bridge and through an old village where shopkeepers and residents stared dumbfounded at this procession of strangers who seemed to materialize out of nowhere. We walked out into the countryside, past a woman washing clothes in the river and another woman brushing her teeth at a rivulet along the road.

Eventually we came to a path that opened onto small fields cut out of the mountain where women were hoeing rows of potatoes and white radishes the size of my forearm. We worked side by side with them for a couple of hours while they tolerated our feeble efforts kindly, occasionally stopping to instruct us in the art of their labor. Afterward we gathered at one of their homes and ate boiled potatoes on a veranda that overlooked the entire valley.

They laugh and chat as they work under the sun. All the expeditioners comment on how happy the people of Palung are. One evening I found myself sitting with Critt Aardema, a cheerful family doctor in Ogden. He noted that he and the other doctors and nurses on the expedition team had screened 120 Nepali patients that day. He said they found a lot of back and neck pain — probably from hauling 100-pound sacks of potatoes on their backs — and some chronic obstructive pulmonary disease — because they cook on open fires in poorly ventilated homes. “But,” he said, getting to the point, “there was no depression or anxiety.” He pauses a moment to let this sink in. “They are all about existence. That’s not what we’d find in the U.S.”

Americans have everything, but they are unhappy, anxious, angry, over-caffeinated, sugared-out and trying really hard to be offended while the Nepalis and much of the world are happy despite struggling merely to survive. One night, when our expedition gathered to compare notes, one of them told the group, “We know how to have indoor plumbing, but we don’t have the other things figured out. They love each other.”

“I came thinking I would do something for them, but they ended up doing something for me,” said Jen.

“It breaks me down,” Mercier told me. “All the cynicism I carry, all the trivial nonsense B.S. I create — it wipes it out. Even if that cynicism comes back after I leave, it’s through a slightly different lens.”

Prateek Sharma, the executive director of Choice Nepal, notes, “It changes our perspective. You see poor people laughing and dancing. We have everything but we can’t laugh and we are not happy. They are happy — why? We have everything financially, but we cannot sleep. They can sleep very well even without good shelter. I have the same feeling. I had never seen that kind of poor people before I went into the village. I just thought they are here,” he said, pointing to his heart.

We are postcards from the world; perhaps the Nepali people are our touchstones.

Some call it poverty tourism (or slum tourism) — tours of white people paying to gawk at poverty. There is a long history of this strange business dating back to 19th century London and continuing today. Forbes reports, “Today, slum tourism has grown into a legitimate global industry, bringing in over a million tourists per year.”

Choice is very sensitive about this. “We do not support poverty tourism and Choice expeditions are not photo ops,” says Riley Greenwood, who oversees the expeditions program for Choice.

The expeditions are a means to an end — helping communities climb out of poverty. The fees paid by expeditioners support Choice’s projects, as well as cover the costs of their housing and feeding. The expeditions are not bus-stop tours in which visitors snap a few selfies and then climb back on the bus and drive to a nice hotel in town. The expeditioners stay in the village; they work and interact with the locals, which is exactly what was intended.

“(The expeditions) increase exposure and awareness of global poverty, to see it firsthand,” says Greenwood. “It’s building global citizens. Recognizing the world is much bigger than they think. There is shared humanity. It brings people together.”

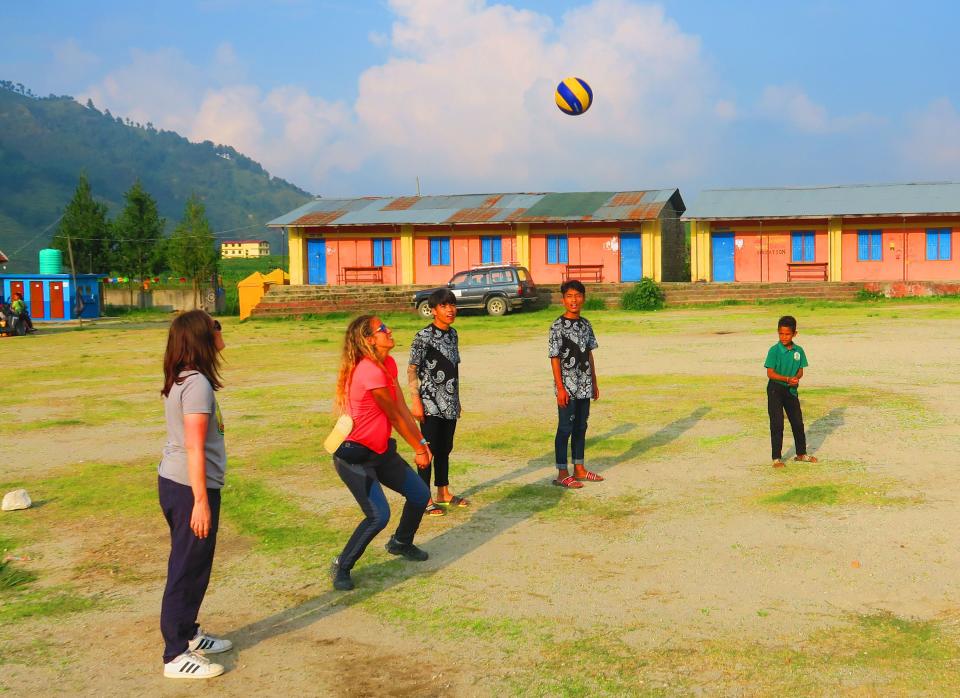

We interacted with the school children throughout the day in our different ways. Some of the women in our group spent hours with the children, reading, jumping rope, coloring and simply socializing. The boys and girls eagerly jumped in to work beside us in their clean uniforms, helping lay the foundation for the new school. In the hot afternoons we played soccer and volleyball with the kids on a dirt courtyard. At the end of the school day, several of us joined them as they formed lines to perform light calisthenics and listen to the counsel of the schoolmaster (actually, I have no idea what he said).

The village children, some of whom speak a little English, are as curious about us as we are them. They are amused by my son’s 6-foot-3 height, which is about a foot taller than the national average for adult males in Nepal. “Tall is good,” one boy says to him, laughing. They are curious about my light colored hair. They are curious about Americans. “Are you rich?” “Show me a dollar.” They ask us to spell our names as they write the letters on their hands. They ask us to take selfies — their term for photos — and then huddle around the photographer to see their image.

Businesses have discovered value in these expeditions, as well. Besides the expedition fees, Choice survives on corporate foundations, grants, individual donors, and a corporate partner program in which companies contribute to Choice via payroll deductions, donations and fundraising events. Some of those companies pay a portion of the expenses for employees who choose to join a Choice expedition.

“Executives of these businesses say it brings a lot to their bottom line,” says Steve Pierce, CEO of Choice. “The corporate culture is enhanced by participating with us. It helps retain employees in a hot employment market. They tell me people are very motivated and proud of their companies for doing this.”

But these are all side effects; the real goal of course is to improve the quality of life in communities around the world. Nepal faces many challenges. The people live in shacks made of corrugated metal and/or whatever material they can cobble together — bricks, rock, stucco. They grow much of what they eat. There are few opportunities for paying jobs, which is why much of the workforce leaves the country.

According to the 2021 census, some 2.1 million Nepalis live and work abroad, where their treatment is reportedly rife with abuse and exploitation. Put another way, 33% of the households had at least one family member working abroad to send money back home, which of course is hard on family life. Sharma notes that about 24% of the population lives on the equivalent of $1.90 a day.

Water is plentiful, but only about 27% of the population has access to clean water, and 80% of the country’s illnesses are due to unsanitary water. Water is at the heart of many problems. There is no indoor plumbing and no running water. Families spend hours each day simply gathering water, which leaves little time for the children to go to school. Schools are too far away for many anyway. So this leaves the usual suspects: Education, health, clean water, food, jobs.

To address these issues, Choice does not give handouts or dictate how or what problems should be remedied. They are facilitators and problem solvers and this approach takes years to unfold. They begin with research to establish a baseline so that they later can quantify the effectiveness of the work. They distribute extensive questionnaires for each family in order to learn who they trust and respect in the community. These are appointed leadership roles in the Choice projects, and some are hired as permanent in-country staff (of the 100 Choice employees, only 13 work in their home base in West Jordan; the rest live in the field). All of the above tends to invest the locals in the project and build trust.

Sharma was a Nepal contractor when Choice hired him as executive director. “I lived without knowing anything else but business,” he says. “When I joined Choice I realized this is my way, my place that I have been trying to find. I started building schools and a health center (with Choice) and when I read the people’s faces and saw their love I felt this is my place.”

Sharma was part of the pilot program in Nepal. According to him, there were 23,000 people in the targeted district who were under the poverty line. “We did a survey and found that most of the people came out of poverty. The impact of the program was massive.” He continues, “The project is selected by the local people. After that we use our skill and relationship capital. We can’t do it without community involvement. If we build a school it’s for them. When they’re involved, then they feel this is mine.”

It can take many forms. They learned that women were vastly underpaid compared to the men when they worked for a third party, so Choice officials introduced the idea of private cooperatives that enabled women to start their own businesses such as farming and earned considerably more money. Looking for opportunities for income, they turned to wintergreen, which flourishes in Nepal. Choice facilitated a partnership with doTerra in 2015 to develop the growing, harvesting and distilling of wintergreen oil for sale by the Utah-based company.

They also taught the people to build greenhouses, which enable them to create climates not only to grow food year-round but to create a climate that is suitable for almost any type of fruit, vegetable and herb that can be consumed or marketed. Greenhouses, which have become ubiquitous here, also use less water and fertilizer. Whatever solution Choice pursues, it must be sustainable. Rye Waterfall, the expedition leader and a native Utahn, recalls seeing a large irrigation project in Peru that had been built years earlier by a well-meaning U.S. company. “It was a very expensive project,” says Waterfall. “Now it was in ruins. The people didn’t know how to use it.”

Because most people in Nepal have little or no access to bank credit to acquire the necessary materials for these and other ventures, Choice offers microloans (even just $200 goes a long way). They charge a small interest rate that allows them to service the cost of the loan and plug more money back into the program so that it’s self-sustaining and can be offered to others. The importance of these microloans can’t be overstated. It provides the freedom for people to break the relentless poverty cycle and start their own enterprise.

“We don’t specialize in any one thing,” says Pierce. “We are problem driven. We try to determine causes and respond with sustainable solutions. We don’t start off by offering something. If you want to work with us, we’ll introduce this method.”

Says Sharma, “The root cause is (people) feel helpless. There’s no one to help. They feel unqualified, unskilled.” He tells the story of a widow whose husband’s family turned her away. She lived under a tarp with no walls for years with two daughters. “She just cried every day for many years,” says Sharma.

“We reached out to her. We are here for you, we told her. We are family. We encouraged her to do a small business of any kind. We asked her to come to business training. It started opening her mind. We gave her a small loan to raise chickens — 5,000 rupees, the equivalent of about $50. She started with five or six chickens. Then goats. She started making some money. After a year she was raising hundreds of chickens and goats. She changed her mentality. She became a leader in the community. She was elected ward chairman. It would be like someone from Pioneer Park (a homeless haunt in Salt Lake City) running for mayor. She started doing things for the community. Choice is building a community of problem solvers. Everyone has potential.”

On our last night in the village, there is a bonfire and members of the Choice staff sing and dance with expeditioners. They have treated us like royalty all week even though what we have done is so small. Sharma surveys the scene. Because of the pandemic, it had been years since an expedition had been here — or to any of the Choice communities. The work went on with the professional teams, but there were no expeditions. The pandemic was devastating for Choice and the other nonprofits. Choice led 31 expeditions across seven countries in 2019, which added up to 900 participants and $1.8 million in revenue. There were two expeditions in 2020 and five in 2021. We are the first to appear in the area.

“During those three years something was missing,” says Sharma. “We had the Choice team here, but it’s not the same.”

I had talked to Pierce, the CEO, before I left home for Nepal. He told me, “It’s not the work that the expeditioners do. It’s the contact they have with the people from those societies and also helping them understand what (the locals) understand about Americans is not necessarily the whole truth. In the work we are doing, bridges are created. I wish we could mandate that. It would help bridge the gap.”

It was the reason Dana and Stephen Scharmann, a nurse-doctor husband and wife team, brought their two youngest children on the trip, just as they brought their two older children years ago.

“We wanted to give them international experience with service and exposure to cultures and the opportunity,” says Dana. “It’s expensive. It costs about as much as I make in a year. But for the first two (children) it was life changing.”

After a few days in Palung, we left the village and pursued something more closely resembling a vacation. We spent a night at the Riverside Springs Resort by the Trishuli River, where we swam, slept in real beds, ate restaurant meals and were serenaded by cuckoo birds in the trees overhead. The next day part of our group traveled to Pokhara and the rest returned to Kathmandu for three days of recreation, rest and tourism.

Before we left the village, the people gave us another grand party, with speeches, music and dancing. It doesn’t feel like we have done much — our contribution was very small, after all — and I wonder aloud why they are so grateful.

Sharma explains. “You all chose to stay in that dirty village. Why did you choose that? They (the villagers) know you could have done something else. We are very grateful. I don’t say namaste to every tourist, but I give it to you.”