The popularity factories distorting what you see on social media

Anyone who visits a website, peeks at social media or logs into a bank account unwittingly becomes part of the ‘online community’. Yes, that’s us. Of course, it’s barely a community at all: it’s a diverse, disparate, unimaginably large group of people who just happen to be using the internet. But that’s not the half of it. Alongside us, visiting the same websites, using the same services and clicking on the same links are an abundance of automated visitors masquerading as real people.

They pretend to be members of that online community. Perhaps potential, or disgruntled, customers. They pretend to like or dislike certain things, maybe YouTube videos or Instagram snaps. They pretend to support opinions – often extreme ones – and sometimes they offer some pre-programmed extreme opinions of their own. Depending on the method of analysis (and this stuff is fiendishly difficult to quantify) as much as half of all internet traffic is fake – driven by fake clicks.

We, the so-called online community, can occasionally spot this as we go about our business. Sometimes the duplicity is conspicuous and we can happily ignore it. At other times it’s less obvious and we might just raise an eyebrow. But even the most tech-savvy among us can end up being unwittingly affected by it. Our idea of what’s popular and what’s not is artificially skewed and distorted by bad actors, out of sight, their methods and motivations almost completely opaque.

“You look at social media, and you think you understand how things got there, but there are so many steps between the author and the viewer that are out of our control,” says Jack Latham, a photographer whose new book, Beggar’s Honey, explores so-called ‘click farms’, one of many methods by which fake interactions are generated.

“I live in West London and my local kebab house has 1,500 reviews, all five stars,” he says. ‘That’s a remarkable amount for a place that seems to have pretty poor hygiene. We know that it’s not real, but we still use these kind of metrics to help us make informed decisions. ‘No one does due diligence in a world where new content is thrown at you every second.’

Latham’s work tends to focus on ‘shady’ subjects – ones that are not always easy to capture, from unsolved crimes to conspiracy theories. “I’m always trying to photograph the unphotographable,” he says. In 2019, he began to think about ways of visualising his new obsession: clandestine web activity that shapes our online environment, and the mechanisms that lie behind it. After inveigling his way into various Facebook groups and making contact with people who sell fake clicks in return for cash, he spent around two months in China and South-east Asia observing their work and photographing it.

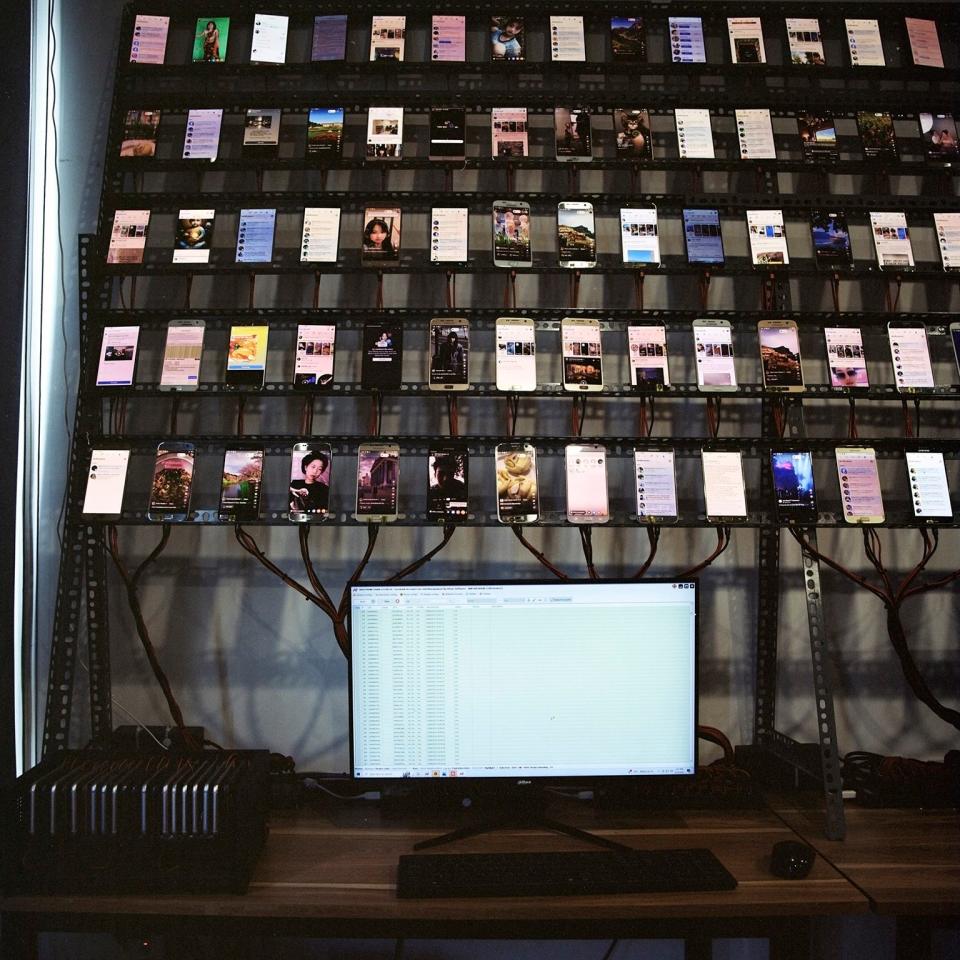

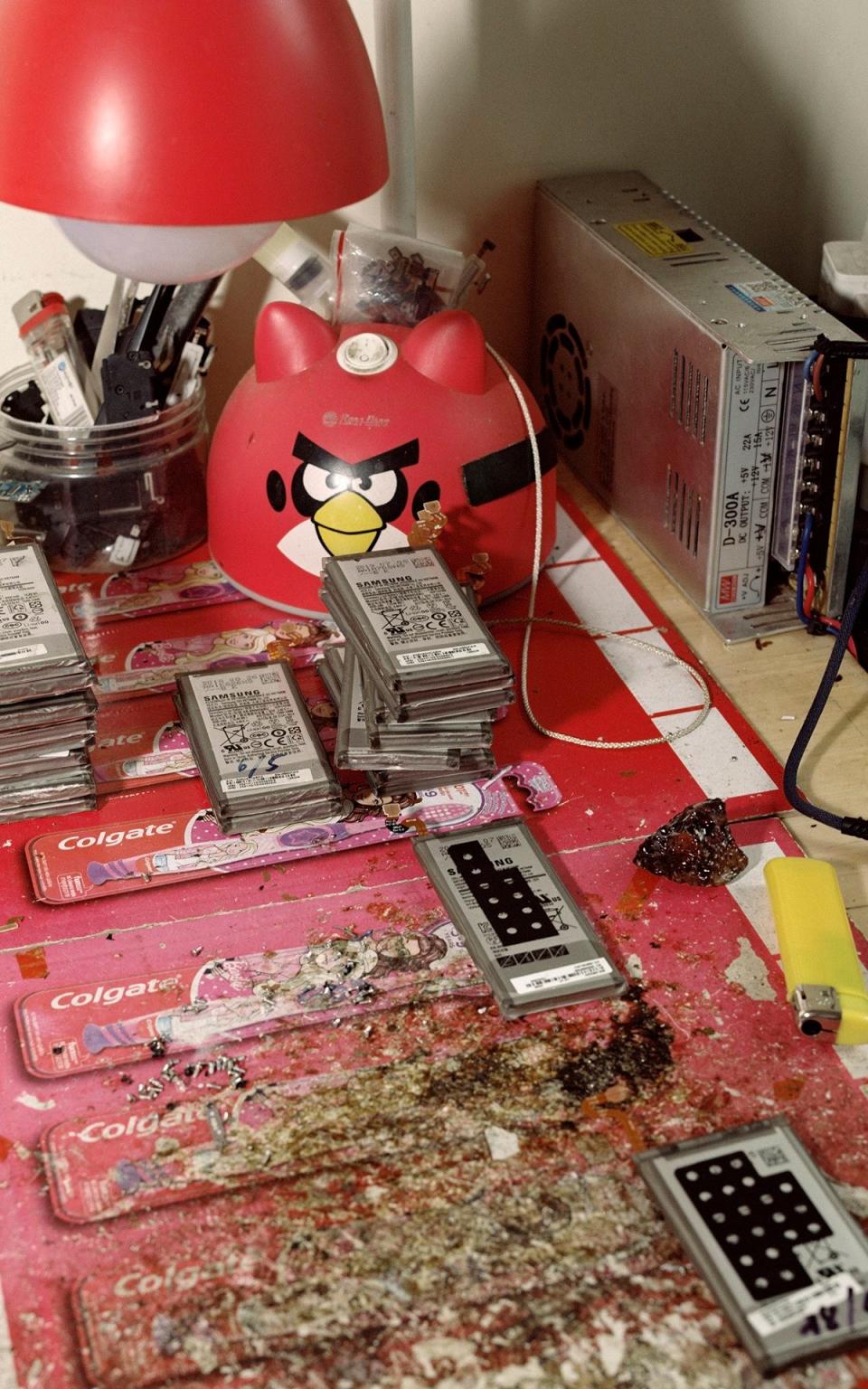

“Click farms are just phones,” he explains. But we’re not just talking about a drawer full. Hundreds upon hundreds of smartphones, their screens and batteries removed, are placed into racks and connected to a single computer. Each phone represents an individual user; one command from the computer, operated by a click farmer, can trigger hundreds of identical likes, follows or star ratings.

In Latham’s experience, these click farmers are typically “young opportunists” rather than career criminals. Nor do they require great big warehouses as one might imagine: a typical set-up fits into a large bedroom or small office. According to Latham, click farmers might receive 0.02 cents (in US dollars) for delivering 1,000 TikTok views, or 11 cents for 1,000 likes on Instagram. This business only works at scale, which is why they’re mainly concentrated in countries with cheap electricity and an abundance of cheap second-hand smartphones.

Latham’s book juxtaposes the click-farm technology with typical images that farmers are paid to click on: anything from selfies to pictures of, say, peacocks or racing cars. “It’s like an Instagram feed, these shiny, colourful, vibrant pictures,” he says. He gathered them by buying his own mini-farm – a box containing 20 phones – from a click farmer he had met in Vietnam and, for the purposes of his project, set himself up as a potential clicker for hire.

“I think my farm is the only one in the UK,” Latham says. “I don’t know of any others – at least, I wasn’t able to find anybody willing to admit it.” Social media as we know it today is less than 20 years-old. Key to its rapid growth was the way that popularity could be easily determined: stars, hearts or thumbs-up could be clicked to signify approval of a post, while friends or follower numbers were prominently displayed. As bigger numbers drew bigger audiences, people sought out ways of gaming the system to give the illusion of popularity, either for financial reasons or just pure narcissism.

“There are enough people in the world who, rightly or wrongly, think that having lots of followers and lots of engagement on their posts is valuable, even if it’s fake and artificial,’ says social media consultant Matt Navarra. ‘Consciously or unconsciously, people will pay attention to some of these inflated statistics, and it will have an effect on the way they perceive the product or the individual – especially if they’re scrolling at speed. That’s why there’s a market for it.’

In 2013, Channel 4’s Dispatches programme uncovered one source of fake engagement in Dhaka, Bangladesh, where teams of workers were paid a pittance to provide the validation in ‘likes’ required (and paid for) by social media users in the West. Their working days were spent clicking what they were told to click, with the aim of encouraging the online community to click on it too. The emptiness of the whole endeavour was palpable.

Since then, these fake engagement factories have become more sophisticated. In 2015, security firm Symantec discovered a piece of malware named Tubrosa, which infected people’s computers with the purpose of secretly opening YouTube links to artificially inflate video views, subsequently monetising them. In time, malware and bots designed to click rapidly and discreetly would become by far the most common form of click fraud, a route to ill-gotten riches for those with the know-how.

Those with fewer resources or coding skills, meanwhile, finessed the farm model, with underpaid workers replaced by the kind of set-ups documented by Latham. In 2017, one such click-fraud operation in Thailand was busted by police and army troops, who confiscated hundreds of iPhones and nearly half a million SIM cards being used to artificially promote products on shopping platforms. It was, and still is, big business.

Another click farm that Latham visited in Vietnam, hidden above a hotel, was dedicated to promoting products via Facebook comments. “In the time we were there, it had left [roughly] 2,000 comments promoting a certain type of hairband,” he says. “It was fascinating – but I thought, hang on, if this is happening with hairbands, what must be happening in the world of political opinion? If your understanding of the world is based upon what you read online, it can potentially be very dangerous if someone is able to manipulate that system.”

Search for the phrase “Honest US citizen here” on X, formerly known as Twitter, and you’ll find dozens of almost identical automated posts expressing support for, or loathing of, President Joe Biden. It makes for a curious, slightly dystopian spectacle, and while it’s impossible to calculate the precise effect of paid-for clicks designed to sway political thinking, Latham for one is convinced that it’s happening.

“I have no evidence to suggest that politicians themselves are doing it,” he says, “but groups of people who believe in certain ideas must surely be.” According to Matt Navarra, the situation will only get worse: “With the advent of AI there’ll be new ways to deceive people, because it has the ability to do things quicker, smarter, and in a more sophisticated way.” In other words: fake traffic will likely look more real, and fake accounts will come complete with convincing back stories.

And yet this activity represents a relatively small proportion of click fraud globally. The vast majority of fake clicks are never seen by the online community, and are steered to where the real money lies: online advertising. By hosting legitimate adverts on their own websites, and then programming bots to click on them, scammers can drain marketing budgets and syphon off huge sums. One click-fraud prevention firm, Polygraph, puts the total figure at around $96 billion per year.

These fake clicks create the impression that a customer is interested in a product, and that the advert has done its job. So the ad platform (perhaps Google or Microsoft) pays out to the scammer and invoices the advertiser. But there never was a customer. The scammer gets its payment per click, and with millions of clicks performed every month, the earnings can be colossal.

“We have some clients who are getting around 80 per cent click fraud,” says Polygraph’s spokesman Trey Vanes. “At the moment, on average, around 11 per cent of clicks on Google Ads are fake. Most marketers are aware of it, but they can’t actually see it happening, so they consider it a cost of doing business. But it can ruin smaller firms. It is not a victimless crime.”

Neil Andrew, CEO of Lunio, another click-fraud prevention firm, agrees. “It’s theft,” he says. “It drives up the price that people are paying for online advertising, and that in turn drives up the price of goods you buy. So ultimately it’s the end users, consumers, who pay for this.”

As for the impact on ordinary internet users, click fraud distorts our worldview, and it can influence our political thinking. It can also persuade us to spend our cash unwisely, plus it drains money from the economy. Tackling it, however, is far from easy. The UK law has struggled to cope with technological change, and click fraud is no exception – not least because it encompasses a wealth of activity that may be illicit but isn’t necessarily illegal, and tracking down the perpetrators is incredibly difficult.

In the advertising world, firms like Lunio and Polygraph offer their services to root out fakes, at a price. But ad platforms such as Google AdSense get paid anyway, regardless of whether a click is fake or real, so – as Neil Andrew puts it, “where’s the incentive to do everything they can?”

In October, a number of firms including Amazon, Booking.com, Expedia Group and TripAdvisor announced a new collaborative initiative to fight fake reviews. Social media platforms, meanwhile, have experimented in recent years by hiding the count of likes and followers in an attempt to make users less fixated on popularity – but as one problem is tackled, others open up.

When Elon Musk began his bid to take over Twitter in April 2022, he pledged to “defeat the spam bots or die trying!” But Latham believes that it’s a losing battle: “The whole thing of Elon Musk’s battle against bots, Mark Zuckerberg’s battle against bots – this is not something that’s ever going to stop, or will ever not exist.”

As for Latham’s own click farm, it is now an exhibition piece: a small green box representing an online environment characterised by confusion and uncertainty. He admits that he did use it to boost clicks, but only once – as a stunt.

“When we announced the book online, I used it to overwhelmingly like the post,” he says. “I typically get between 500 and 1,000 likes, and it has something like 7,000 or 8,000 now. But I was trying to make a point.”

Enjoy this example of click fraud that comes with a candid admission. It may be the only one you ever see.