Portland protesters were beaten, shot at and snatched. Years later, they are frustrated by legal blockades to accountability.

- Oops!Something went wrong.Please try again later.

PORTLAND, Ore. — A phalanx of federal officers emerged from the U.S. courthouse in downtown Portland on the night of July 18, 2020, and advanced on protesters standing nearby.

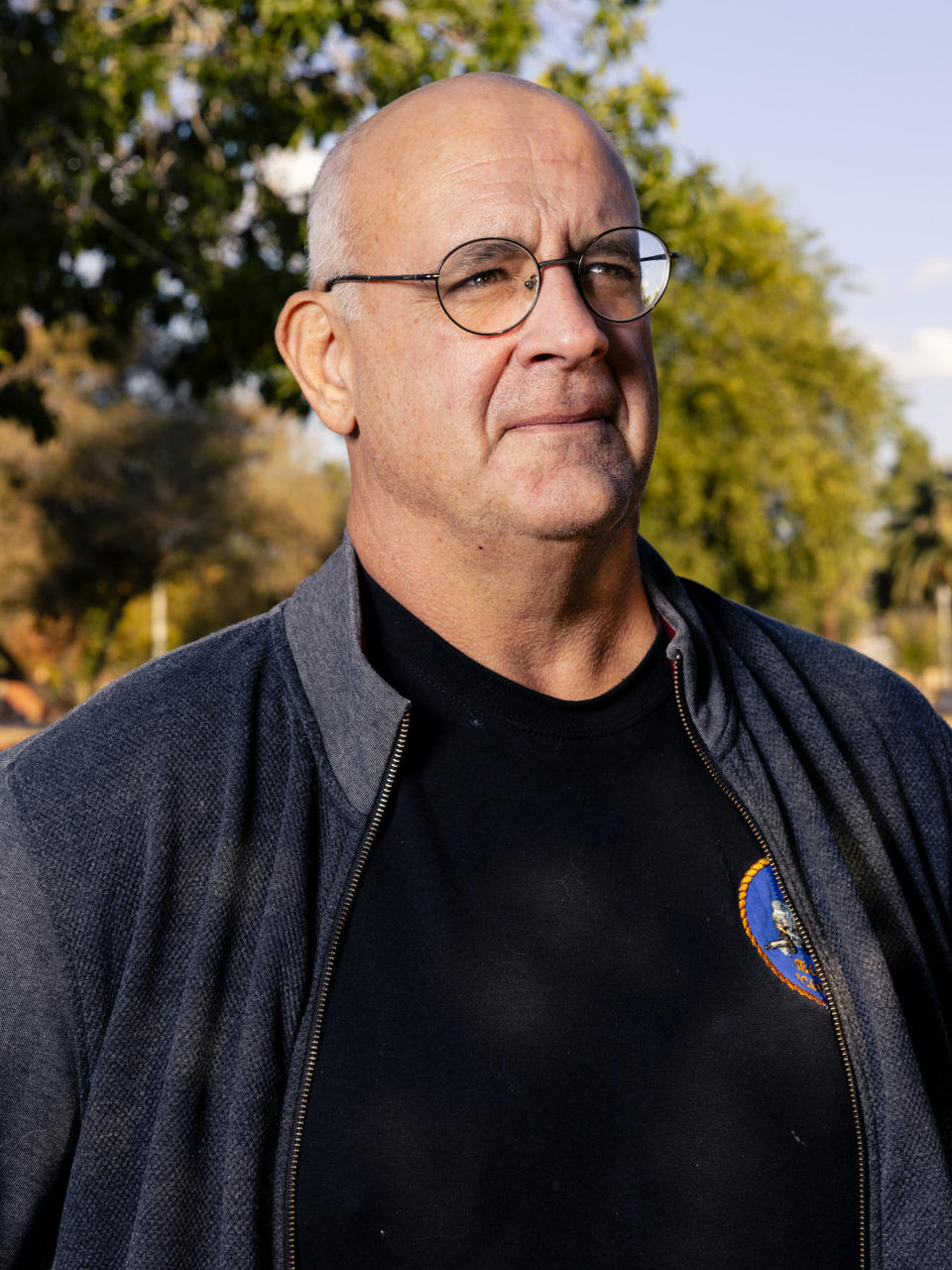

Chris David, from the park across the street, saw the officers plow into the protesters, knocking several of them to the ground. For weeks, nightly racial justice protests in the wake of the death of George Floyd in Minneapolis had roiled the city, and federal officials responded to intermittent violence with an influx of law enforcement.

The Navy veteran had never participated in a protest before, but that night he decided to see for himself after watching with growing unease as the number of federal officers increased at the direction of then-President Donald Trump. David walked up to the line of officers, who were wearing body armor and carrying weapons.

“I stood there and I started asking them the same question over and over again: ‘You are violating your oath to the Constitution. Why are you violating your oath to the Constitution?” David said in an interview.

He never got an answer.

He stood facing four masked and helmeted officers, later identified as deputy U.S. Marshals. One officer appeared to push David, who stumbled backward before regaining his balance. At that point, David said one of the officers pointed a firearm at him.

Another officer then hit David repeatedly on his left side with a baton, he said, while another sprayed him in the face with a chemical irritant.

David stumbled away, his hand broken in two places. The video footage quickly went viral.

He subsequently joined a federal lawsuit accusing individual officers of violating his constitutional rights. These are known as “Bivens claims” after a 1971 Supreme Court ruling that allowed such lawsuits.

The Untouchables: NBC News investigates how federal law enforcement officials are able to harm people with little to no accountability.

It was important to him, he said, that the officers be held accountable for their own actions, regardless of what they had been ordered to do. When he studied at the Naval Academy, he added, “one of the first things they taught us is that you are never to follow an illegal order. Ever.”

The explosive protests of that summer are slowly fading into history, but three years later those who were involved are still struggling — both in court and in some instances in their daily lives. David is just one of many protesters who accused federal officers of being overly aggressive, whether it be by striking people with batons, firing nonlethal projectiles or, in more than one instance, allegedly snatching people off the street without explanation.

But not a single federal officer on the Portland streets at that time has been held individually accountable for alleged constitutional violations over claims brought by David and other protesters. In fact, courts have not had a chance to assess whether constitutional violations even occurred.

That is thanks to the intervention of the Supreme Court, which in a series of rulings has created an accountability-free environment in which federal officials interacting with the public on a daily basis, whether it be a bureaucrat sitting behind a desk, a corrections officer in prison or an FBI agent conducting a raid, can violate people’s constitutional rights with impunity.

As NBC News has reported, a 2022 Supreme Court ruling in a case called Egbert v. Boule has had broad repercussions nationwide. At first glance, it concerned only claims against Border Patrol agents, but the impact was far broader.

A Chinese American person could not bring a Bivens claim against FBI agents after being wrongly charged with being a spy. A woman could not sue Social Security Administration officials for incorrectly declaring that she was dead. A Hispanic man could not pursue his claim over his wrongful arrest after U.S. Marshals detained him in a case of mistaken identity.

NBC News data shows that, in the 12 months since Egbert was decided, plaintiffs have lost cases against an alphabet soup of federal agencies, including many that have nothing to do with border or immigration issues. In case after case, judges cited the Egbert ruling in refusing to allow Bivens claims.

Cases involving claims made by federal prison inmates have been among those most affected.

Of 228 cases identified by NBC News that cited Egbert in dismissing Bivens claims in the year after the ruling, 142 involved claims by federal prisoners, many of whom did not have legal representation. Prison officials prevailed in 123 of those cases. In one, a female prisoner was barred from pursuing a claim that she was sexually assaulted by a prison officer. Several cases involve claims arising from the treatment of prisoners during the Covid-19 pandemic, including one in which a judge dismissed a claim that an inmate who died from Covid-19 had not received proper medical treatment.

James Pressley, who was formerly incarcerated at a federal prison in Terre Haute, Indiana, and contracted Covid in 2020, joined a lawsuit saying not enough was done to protect inmates, therefore violating his right to adequate medical care under the Constitution’s 8th Amendment, which prohibits cruel and unusual punishment. Pressley was released from prison after his drug-related convictions were thrown out on appeal.

In total, seven inmates died of Covid at the federal prison complex in Terre Haute, which includes two different facilities. The Bivens claims were dismissed in January this year.

“In my opinion, Bivens needs to be reconsidered due to the fact that it gives officers free rein to do whatever they want without facing the proper consequences,” Pressley said in an interview. “Even though inmates have been proven guilty, they still have human rights. And when you violate human rights, that’s still a violation of the Constitution.”

Judges made clear in various other rulings that they had got the Supreme Court’s message. In one ruling in favor of prison officials over an excessive force claim brought by an inmate, Judge Bobby Baldock of the Denver-based 10th U.S. Circuit Court of Appeals wrote that “lower courts expand Bivens claims at their own peril.” In a decision tossing out another prison inmate’s Bivens claim over inadequate health care, Hawaii-based District Court Judge Derrick Watson said that the Egbert ruling “tightened the noose around Bivens.”

In a dissenting opinion published last month in another case dismissing a prisoner’s Bivens claim, Judge David Hamilton of the Chicago-based 7th U.S. Circuit Court of Appeals said such lawsuits are ever more important at a time when allegations are swirling of federal agencies being weaponized to punish political opponents.

But, he wrote, because of the recent Supreme Court rulings, “a federal agent who violates the Constitution to carry out the policies of the federal executive branch now has little to fear in terms of direct accountability.”

'Zero Bivens cases'

The volatile situation in Portland in 2020, with hundreds of federal officers facing off against energized and sometimes violent protesters meant that David’s encounter was just one of many that ended up in court.

Duston Obermeyer, a military veteran who was standing near David when federal officers advanced, was struck and sprayed with a chemical irritant.

Mark Pettibone alleged he was snatched off the street in the early hours of July 15 and shoved in the back of an unmarked van.

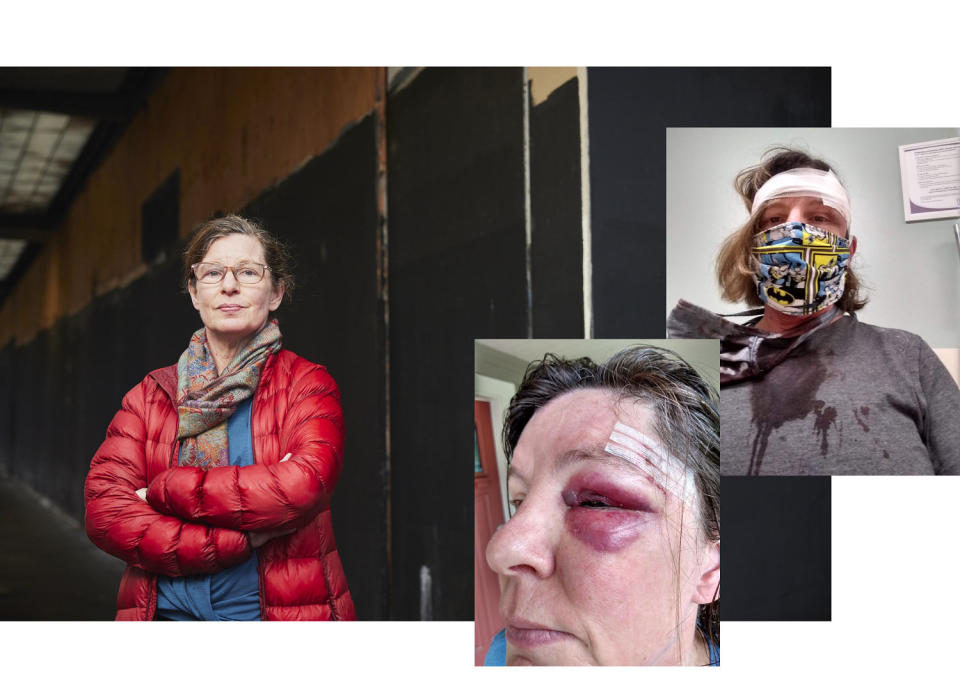

Maureen Healy, a history professor, said she was injured by a nonlethal projectile fired by officers on July 20.

Donavan LaBella was hit in the head by a nonlethal projectile on July 11 while standing in front of the courthouse in another incident caught on video.

They are just some of the other Portland protesters whose constitutional claims have fizzled.

“The motions to dismiss should be granted because the U.S. Supreme Court’s recent decision in Egbert v. Boule forecloses the availability of a so-called Bivens cause of action,” wrote U.S. Magistrate Judge Youlee Yim You in a September 2022 decision recommending that the claims made by David, Obermeyer and Pettibone be dismissed. U.S. District Judge Michael Simon later endorsed her findings.

In total, judges in Portland concluded they had to throw out Bivens claims in five cases. In three cases, the rulings explicitly cited Egbert in dismissing the Bivens claims.

In three other Portland cases, plaintiffs dropped their Bivens claims in light of Egbert, concluding that it was futile to continue. Some Bivens claims in Portland cases are technically still alive, but only because attorneys have ceased pressing them amid difficulties in figuring out the identity of the officers they are trying to sue.

Portland plaintiffs have other claims pending, but they are not against the individual officers in their personal capacities seeking damages for constitutional violations.

“Three years on, we have not had a trial on what occurred in 2020 involving federal officers and now it might never happen,” said Juan Chavez, a Portland-based civil rights lawyer.

In the Egbert decision, the Supreme Court ruled 6-3 that individual Border Patrol agents cannot be sued for constitutional violations, saying that such claims have to be specifically authorized by Congress. The court rolled back a 1971 precedent called Bivens v. Six Unknown Named Agents that, for the first time, held that federal officials could be sued for constitutional violations in the same way that state and local officials can be sued under the 1871 Civil Rights Act.

The court had ruled in favor of a man called Webster Bivens who brought excessive force and unlawful search claims against federal agents who entered his apartment without a warrant and handcuffed him in front of his family. As a result, “Bivens claims” were born.

The Supreme Court initially expanded on Bivens in two further rulings. In 1979 in a case called Davis v. Passman, the court allowed a due process claim over sex discrimination carried out by a member of Congress against an employee. The following year the court in Carlson v. Green, endorsed claims of medical indifference brought against federal prison officials by an inmate.

That was as far as the court would ever go. The tide began to turn in the early 1980s, and in case after case since then the Supreme Court has refused to extend Bivens to other contexts. That trend has continued in recent years. In 2017, the court declined to allow federal officials to be sued for the roundup of Muslims in New York after the Sept. 11, 2001, attacks in a case called Ziglar v. Abbasi. Two years later, the court in Hernandez v. Mesa ruled in favor of a Border Patrol agent seeking to avoid a civil rights claim for killing a Mexican teen who was standing on the other side of the U.S. border.

The sense that Egbert overturned Bivens in all but name is emphasized by the fact that judges are dismissing claims even in cases in which the facts bear some resemblance to the three instances in which the Supreme Court had explicitly endorsed Bivens claims.

In one case, a woman could not bring an excessive-force claim against FBI agents after they used flash-bang grenades during a search of a neighboring apartment. In another case involving a raid, a man could not sue Immigration and Customs Enforcement (ICE) agents for using excessive force against him even though he was not the person they were seeking.

If an incident like the one in Webster Bivens’ case happened today, even he “probably doesn’t have a claim under Bivens,” said Nadia Dahab, a Portland lawyer who represented protesters in other cases arising from the 2020 unrest.

As has been shown in Portland in the cases in which Bivens claims have been dropped, lawyers representing plaintiffs have taken note.

“In the past 12 months I have filed exactly zero Bivens cases,” said San Diego-based plaintiffs’ lawyer Julia Yoo.

‘Operation Diligent Valor’

More than three years after the Portland protests, a security fence still stands outside the Mark O. Hatfield Courthouse downtown and visitors still have to enter via a side door because the original glass-fronted entrance remains boarded up.

On a recent weekday, there were no visible federal officers standing guard and the protesters who used to gather in the park on the other side of SW 3rd Avenue are long gone.

Soon after the protests began on May 29, 2020, the federal courthouse — a modest tower built in the 1990s that in the eyes of protesters took on the appearance of a fortress — became a focus of the crowd’s anger and frustration. The bulk of protesters were peaceful, but there were outbreaks of violence, including vandalism and attacks on law enforcement officers.

In the midst of this volatile situation, Trump issued an executive order on June 26 ordering his administration to assign personnel to protect federal property. This led to the Department of Homeland Security to launch that same day what it called “Operation Diligent Valor” to assist the Federal Protective Service in protecting the Portland facilities. The Marshals Service, which is part of the Justice Department, was involved separately as part of its normal role providing security at federal courthouses.

Before the unrest began, just seven full-time FPS officers were protecting federal facilities in Portland. From June to August, 755 DHS officers ended up involved in Operation Diligent Valor, according to a subsequent report by DHS Inspector General Joseph Cuffari that found fault with how the plan was implemented.

With federal officers, who often lack proper identification badges, gathered not only on the street but also on a rampart-like platform that overlooks the park, “it felt like an alien invasion,” said Chavez, the civil rights lawyer.

Billy Williams, who was Oregon’s U.S. attorney at the time, had a different perspective: His office was inside the building.

While most protesters were peaceful, he saw graffiti, broken windows and other property damage as the courthouse became a target. He and other federal employees faced harassment as they tried to enter and exit the building.

During the daytime the protesters were overwhelmingly peaceful, but at night “things started getting out of hand,” Williams said in an interview at a coffee shop directly behind the courthouse.

“The fact of the matter is somebody needed to be protecting the buildings,” he added.

In defending the actions of the federal officers, government officials and lawyers for individual officers repeatedly highlighted in court papers the rapidly changing, dangerous situation in Portland at the time, as well as the legal authority officers had to disperse crowds when local police declared an unlawful assembly. They also cited the Supreme Court’s recent decisions in urging judges not to allow Bivens claims.

In a court filing seeking to dismiss David and Obermeyer’s claims, lawyers for two unnamed deputy U.S. Marshals sought to differentiate their case from those in which the Supreme Court had previously allowed Bivens claims, writing that the court has never endorsed claims related to “the protection of federal property” or against deputy U.S. Marshals.

“Bivens actions based on excessive force have only been extended to contexts where the use of force was incidental to the exercise of law enforcement search and arrest powers, not the exercise of statutorily enumerated powers directed at the protection of federal property,” the lawyers, Justin Rusk and Ross Nabatoff, wrote.

In a joint interview, Rusk and Nabatoff said they did not believe that their clients had used excessive force in carrying out their mission to protect federal property but added that the deputies were subject to an internal investigation.

Talking generally about the investigation process, Nabatoff said that officers can be reprimanded, suspended, or fired if there is a finding of wrongdoing.

“That can happen once in a while,” he added.

Other lawyers representing officers declined to comment and did not make their clients available for interviews.

It remains unclear if any federal officers were disciplined internally or are likely to be as a result of their actions. DHS and the Justice Department declined to comment. An investigation by the Justice Department’s inspector general into the use of force in Portland is ongoing, a spokeswoman said.

During the protests, hundreds of protesters were arrested. Prosecutors, local and federal, pursued criminal charges in about 300 cases. The federal government estimated that the cost of the damage to the courthouse facility was $1.6 million, while Operation Diligent Valor as a whole cost $12.3 million.

Although former U.S. attorney Williams thought the Trump administration rhetoric was too divisive, he does not fault the federal response as a whole.

“I don’t think it got out of hand. I think they were brought in in a very challenging set of circumstances,” he said. If individuals did something improper, “that’s a different issue. That’s why you have an investigation,” he added.

Several Portland plaintiffs who spoke to NBC News expressed outrage that their constitutional claims cannot move forward, even though in some cases they can pursue other remedies that could lead to payments from the federal government. But without constitutional claims, there is little deterrent effect for individual officers.

“I think myself and people who are pessimistic about policing and the way the federal government works, we haven’t been proven wrong yet. We’ve only been proven right,” said Pettibone, who was detained briefly and released without charge after being snatched off the street.

To history professor Healy, who suffered from a black eye and concussion after being hit in the head, her whole experience gave her the sense that history was repeating itself. Having taught on authoritarian regimes of 1930s Europe at Lewis and Clark College, where she works, she saw some parallels.

“It felt to me as a historian that things were escalating under the Trump administration that summer in a direction that it was really starting to kind of fit the bullet points of authoritarianism,” she said in an interview in her lawyers’ high-rise conference room in downtown Portland.

“I think it’s especially important given the state of politics today that we have federal accountability,” she added.

Obermeyer, the veteran standing next to David who was struck and temporarily blinded after being sprayed in the face, made a similar comparison, noting in an interview that the Nazis on trial at Nuremberg after World War II had tried to claim they were just following orders.

“It didn’t work for the Nazis at Nuremberg. It shouldn’t work in the United States either,” he said.

David, like other plaintiffs, still has separate claims pending against the federal government. But even though he could still win damages, his case is now solely against the United States government and not the individual officers.

Drawing on his background in the Navy, he said that a successful lawsuit against the officers could have helped foster discipline in the ranks and act as a deterrent.

But now the opposite message has been sent.

“If you’re employed by the federal government you can take almost any illegal or unconstitutional behavior against somebody else and you’ll never be held accountable for it,” he said. “It’s absurd.”

CORRECTION (Dec. 14, 2023, 10:15 a.m. ET): A previous version of this article misspelled the last name of a Portland lawyer who represented protesters in the 2020 unrest. She is Nadia Dahab, not Dehab.

This article was originally published on NBCNews.com