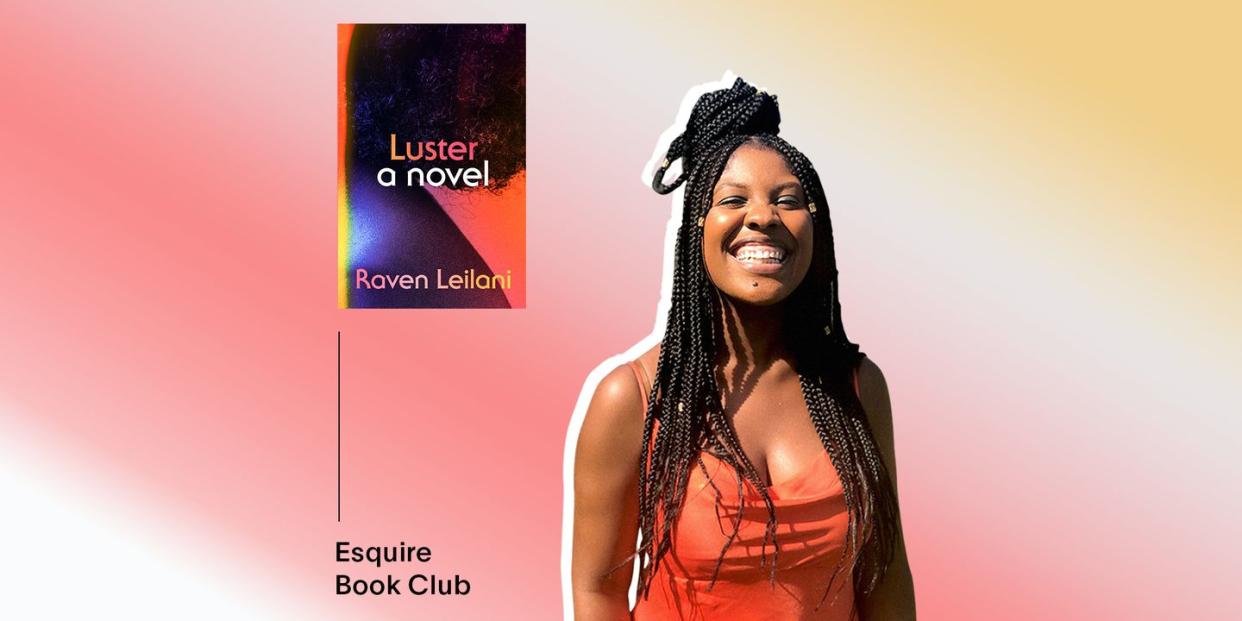

Portrait of the Artist as a Young Black Woman: A Conversation With Raven Leilani

Meet Edie. 23, lonely, and rudderless, Edie is drifting ever closer to self-destruction. After losing her dead-end admin job in a publishing office rife with racism and misogyny, she turns to delivering takeout by bike in order to make the rent on her squalid Bushwick apartment, where she spends her nights growing in fits and starts in her development as a painter. Meanwhile, she’s sleeping with Eric, a much-older man in an open marriage, whose carefully constructed boundaries come crashing down when his enigmatic wife, Rebecca, invites a destitute Edie to stay in their suburban home. There Edie meets Akila, the couple’s recently adopted Black daughter, to whom Edie grows close when she realizes that she may be the only Black woman in this teenager’s life.

Edie is the protagonist of Luster, a blistering, singular debut novel by Raven Leilani. Raw, racy, and utterly mesmerizing, Luster is among the most dazzling novels of the year, marking the arrival of a major new voice in American letters. Edie’s voice is unforgettable, with Leilani bringing painterly precision and biting humor to a feverish novel where each pyrotechnic sentence is a joy to experience. Dreamlike, tender, and big-hearted, Luster is a must-read from an immeasurably talented new writer. Leilani spoke with Esquire about failure, performance, and the adversarial relationship between art and capitalism.

Esquire: Where did this novel begin for you?

Raven Leilani: It began during the second semester of my first year in NYU’s MFA program. It took a little over a year to write, but I worked on it in a number of workshops. As I wrote, the themes that creep into everything I do began to emerge: art, God, Blackness. I wanted to tell a story about the journey of making art, and I wanted to speak to its messiness. I wanted to speak to how that trajectory is non-linear, because it had been for me. As I wrote, I was working full time at Macmillan; I was also in school full time, and I had a couple of part-time gigs. That’s the state in which I’ve almost always been writing. All the short stories and all the books I'd tried out before this one had always been written outside of that “9 to 5” window. I think you can feel that in the text—that anxiety of balancing feeding yourself and making art.

ESQ: Edie is such a deliciously complex character. What was your process of developing her and finding her voice?

RL: One of my workshop mentors was Zadie Smith. She pushed me to be brave in depicting a human Black woman who makes mistakes. Any person coming from a marginalized community or writing about a marginalized community knows that, if you can get any space for your work, you want to speak to the joy, and you want to represent well. When you’re writing a character who’s fucking up all of the time, there's the very real question of, "Do I have a responsibility to write a pristine story?" But most writers would agree that your responsibility is to tell a human story. We have a lot of people and institutions that police Black women's behavior and feelings; that speaks to what's in the novel, where Edie is involved in a number of performances depending on the space she's in. That's the real world. You survive by studying, by calculating. It was important to me to represent the part that is messy and human, and to make room for a character who is not pristine, because that's who I am, and that’s who people are.

I tried to write against the idea that there is a specific way to conduct yourself to be afforded humanity. Wading into these waters is very fraught; the unlikeable woman is in the ether, and she has been for a long time. Often when we talk about that concept, it means we've seen the dark underbelly and interior of a woman's mind. I'm not saying that I wanted to write an unlikeable woman, but rather a complex woman. One that holds contradictions, as we all do.

Esquire: Edie feels raw and real not just in her interior life, but in her artistic life. You depict her failures, her frustrations—even moments where she throws her paintings in the trash. Why was it important to you to depict a Black woman not just making art, but failing at it?

RL: Failure is 80 percent of it, if not more. I wanted to speak to that, because it’s liberating to me. I hope it will be liberating to readers to see an unvarnished depiction of the art-making process. Making art is so much about failure, but also so much about redemption—about weathering the failure, and still keeping the faith that what you have to say is necessary. Before I got to this book, I had been submitting stories for over a year. Most of what I sent out was rejected. I kept an Excel spreadsheet listing all of my rejections. Itemizing the first one really hurt, but then as I went on collecting those rejections, it began to feel like proof that I was putting the work out there. Failure is instructive, and it’s such a huge part of the process.

As for Edie, so much of her time is spent trying to satisfy those primary goals. How to eat, how to pay rent, where to live, how to pay her student loans. Bracketing that under the umbrella of failure is not quite the right word, because in the pursuit of art, your ability to make anything is influenced greatly by your economic and social state. Pretty much everything I've written was written after whatever “9 to 5” I've had. I looked at my resume the other day; it's just a string of random jobs. I wanted to talk about the part of making art where that dream is deferred over and over and over again, especially because of conditions that you have no control over. Edie exists in the world as a Black woman; she feels the performances demanded of her depending on the environment she's in. Sometimes she has to put the art down for awhile, because the vision in her head is not quite translating. I wanted to speak to how extremely demoralizing that is, being unable to communicate the world as you encounter it.

I think that art, at least the art that I like to talk about or write about, is communicative. When you can't make it, it is deeply frustrating; it's sort of like an unresolved pressure you hold within yourself. I wanted to speak to those parts, because there's one way of talking about art, which is that you put in the hours and you do it. But there’s another way of talking about it, too. When I talk to writers about writing, most of the time, we’re talking about not writing.

ESQ: I love that about this novel—how so much of it is about Edie's struggle to stay professionally and financially afloat. We see her in a white collar job where she's underemployed and demeaned. We see her in the gig economy, where she's hustling so hard she almost drops. We even see her interview for a gig at a clown school. Certainly this is a novel about relationships, but it’s also a novel about work.

RL: That was important to me. Don't get me wrong; I have a real soft spot for books that are just about relationships. I love that. But there's always a different kind of engagement and love I feel for writing that involves the dimension of work. That's actually what we spend most of our lives doing. I wanted to talk about how work and art have a symbiotic, but also adversarial relationship. You need money to live and eat, and then to make art, but the job you have can become the thing making it so that you cannot do any living, because you've spent that bandwidth trying to live. I’ve felt that so deeply in my own life, and in the lives of so many women I know.

ESQ: You’re a painter as well as a writer. What do you bring from one discipline to the other?

RL: Painting was my very first love. At the beginning, I thought I would be a cartoonist. I really just took to it, and I was lucky enough to go to a public school that had a rigorous art program. Critique was central. We’d talk about what was working or what wasn’t working. The fact that I was lucky and privileged enough to be in such a rigorous program was hugely important in how I began to think about art. Not as something that is perfect the moment it comes out of you, but something that is a process—something that is made better by feedback. Like rejection did later in my life, it hardened me. It hardens you in a way that is absolutely necessary to stick it out.

I stepped away from painting because I just didn't have it. I truly didn't have the technical skill that you need to make it. I didn't have the will to pursue it professionally, so it became a private activity that I did when I got the bug to paint. I'm glad I did that, because it feels more like mine. Writing is different in that, even when it's hard, I really love it. I really have the will to work for it. In writing, I've gravitated toward writing about painting, because painting is a difficult and vulnerable task. It also just feels really great to write about, because I love color and I love image. I think my writing bears that.

A post shared by Raven (@raven_leilani) on Jul 3, 2020 at 6:40am PDT

ESQ: Edie has such a fascinating relationship with Rebecca. Why was the tension and the strange intimacy between these two women so interesting to you? What binds these two characters together besides one man?

RL: I think that Eric becomes irrelevant to their connection very quickly. When I started this book, I knew that I was going to write about a woman getting in the middle of an open marriage; there's a way to write that where two women fight over a man, but that's not particularly interesting or true to me. I wanted to speak more to the interior lives of these women. I wanted to speak to the wants in both of them, because they're both seeking something.

Relationships between women are so chewy. They can be so romantic. There are certain kinds of relationships between women that are immediate—they proceed without preamble. There are no frills; you get to know one other immediately and profoundly. There’s something really complex and intimate about the way women reveal themselves to each other, and what they choose not to reveal. With Rebecca and Edie, it's complicated, because there’s an unbalanced power dynamic at play. Rebecca is white and comfortable, while Edie is coming from a place of extreme precarity.

Edie is often looking to men to affirm her personhood and her artistry, and she's often disappointed. In my life, it's been women who have lifted me up and seen me, who have made me feel valid in what I was making. Edie and Rebecca’s relationship is fertile in the way that it facilitates a different kind of rigor in Edie's work. There are so many differences that they need to reconcile as they fully come together, so I wanted to make space for that, too. I wanted to take their differences seriously, because the differences between them are fundamental. You have two people who are coming toward each other, which is complicated by the steps they have to take back because of their differences. It becomes this dance of delayed gratification, which is almost erotic. I wanted to speak to the romance of meeting another woman who both affirms your seriousness and challenges you.

ESQ: Speaking of eroticism, you write such stunning sex scenes—full of lyricisim and poetry, but also extremely frank about the embarrassments of living in a human body. Yet some writers feel uncomfortable writing sex scenes; others avoid them entirely. When you write a sex scene, what are your priorities, and what’s your approach to getting it right?

RL: I’ve somehow remained insulated from the idea that there's no place for sex in literary fiction. I'm only now looking into it, because I’ve been frankly surprised by the response to those sections of the book. How I approach sex is how I approach character in general. In these scenes where people are ostensibly laid bare, I want to make room for the parts that are ugly or contradictory. In that space, especially because this book is dominated by Edie's many performances, there is no curation. Sex is a place where people are always subject to managing the expectations of their partner or being careful in what they reveal. It’s also an avenue to explore character and power. The books I love that talk about sex are relentless in their representation of what it looks like when people have sex. The way that intimacy manifests is an awkward, silly, ugly thing. A pristine representation of what sex looks like doesn't feel true or interesting. I tried my best to create an honest depiction—what it looks like when sex is good, but also when it's bad. I want room for pleasure and tenderness, but also the parts that are strange.

ESQ: You mention power, which makes me think of a line early in the book where Edie discusses her attraction to older men, saying, “There is the potent drug of a keen power imbalance.” What’s so seductive about a power imbalance, both in life and on the page?

RL: Edie likes it. It’s important to say that she is seduced by that. It’s seductive in part because she is a person who is deeply studied and engaged in the performances required of her. She lives in a world that is deeply pressurized because of the intersection of identities she lives in. There is an element of surrender to that power, which turns the valve and releases the pressure. There's also a kind of envy and a deeply Freudian jealousy in engaging with the person who is apparently more powerful than you. Edie is fumbling through the dark in search of intimacy and human connection. She's seeking power. There’s something seductive in being powerless, and having any kind of connection to someone who has power almost casually, as Eric does. It's an interesting way to understand yourself.

It's so tricky to talk about this relationship, because it doesn't exist outside of real life, in which relationships are subject to the power of social, economic, and racial context. It’s hard to articulate why a young Black woman is seeking that kind of obliteration. But I think there’s a freedom in that, in Edie’s agency, in saying, "I want that." In that obliteration or surrender, there is feeling, but there’s also a release from feeling.

ESQ: In one wrenching scene, Akila is wrestled to the ground in her front lawn by police officers who refuse to believe that a young Black girl could live in an affluent neighborhood. Certainly that scene was contemporary when you wrote the book, but in the months since, the country has been rocked by a groundswell of political activism about police brutality and racial justice. What are you feeling as you release this novel into this political moment?

RL: When I wrote this book, I was trying to report what I saw. Anyone who's Black and trying to navigate these intersections is aware of what's going on. It makes its way into our art. In fiction, the suburbs are typically a place of boredom and ennui, but it's not so for a Black woman. As soon Edie arrives, she understands she's being surveilled. Akila confirms it. No matter where you are, there’s a precarity. Your body is in peril in a way that’s constant. I wanted to speak to a quote I’d read about how one of racism’s main functions is to exhaust you, between the hyper-surveillance and the inherent and silent threat around your body. Work contributes to this; needing to feed yourself and subject yourself to the demands of capitalism also does this. But then there’s the added pain of having to justify that you live where you live. Having to contend with the white imagination at all times, and be human, and live, and thrive, and make things. It is impossible. It’s a pressure that has impeded not just Black artists, but Black people, in pursuing a free, beautiful life.

I wanted to talk about that exhaustion in this book. Not just exhaustion, of course, because I want to be careful in framing Blackness in relation to trauma, but it isn't irrelevant to talk about the way that this constant hyper-vigilance deteriorates what we have to give elsewhere. For a young artist who's trying to make art and connect with people, this too is something she's contending with. I wanted to speak to the absurdity of having to contend with that.

You Might Also Like