Portsmouth South End stalwart Harold Whitehouse: 'I've got memories like crazy'

Harold Whitehouse Jr., 94, reached out to the Athenaeum after seeing a column about a photo of Franklin Delano Roosevelt's July 1932 campaign stop in Portsmouth. He recalled seeing FDR years later during a visit the president made to the Portsmouth Naval Shipyard.

"I was 11 years old. My mom took me," he said. "It was at the corner of Daniel and Market streets. FDR was in an open car; he had that cigarette holder in his mouth. I was so excited I went back and told all the kids at school."

At the time, he attended the Haven School, next door to his South School Street home and the anchor of his South End neighborhood.

"My family would sit down every afternoon at 5 p.m. and talk at the supper table," Whitehouse said. "My mom would say, 'Did you bring home papers with gold stars?' Mom loved that. I was the oldest of six — there were three boys and three girls."

His mother, Grace Berry Whitehouse, would also remind the children: "I stood over a hot stove all day cooking this meal and I hope you appreciate it."

Harold Enoch Whitehouse (Harold Jr. was named for his dad, minus the middle name "Enoch," which Grace did not like) had grown up poor, but managed to get a job during the Great Depression cutting trails in the White Mountains with the Civilian Conservation Corps, one of FDR's New Deal programs.

The junior Whitehouse joined the Navy in June 1946 just before he turned 18. He said his mother supported him signing up because she hoped he would use the GI bill to get an education or apprenticeship once he left the Navy. He served aboard the USS Macon for 18 months, then was reassigned to the overhaul of the USS Missouri at the Brooklyn Navy Yard and completed his service, he thought.

More: Portsmouth seeks volunteers to shape new cultural plan: How you can get involved

In October 1948, he started an apprenticeship with the Portsmouth Herald, training as a pressman and Linotype operator. At the time, the newspaper's office was on Congress Street and its pressroom was on Porter Street, "right across from the Music Hall," he said.

"The publisher, J.D. Hartford, would meet you on Friday afternoon, carrying a long box with money in envelopes," Whitehouse recalled. "He would say, 'Thank you very much, Mr. Whitehouse. The Herald made some money this week and we thank you for your service.'"

He started at the Herald making $85 a week, with the U.S. Department of Education making up the difference between what he was paid and journeymen's wages.

Whitehouse would go on to work for the Herald for 28 years - though in January 1951 he was called back into the Navy, working 16 months at the South Boston Naval Annex to help re-fit the carrier escort Kula Gulf for the Korean War. He lived on the ship while the work was done.

He returned to the Portsmouth Herald, leaving when it was sold in 1968 and he was laid off. He then got a job at the Portsmouth Naval Shipyard, where his father had also worked.

"He started as an assistant electrician, was promoted to full electrician and ended up as supervisor of the power plant at the shipyard," Whitehouse said. "My father sat me down at 12 and said, 'Don't be ashamed to get dirt under your fingernails. Do something physical - don't work sitting at a desk. At the end of the day, you can look at something tangible, something you are proud of doing.'"

Whitehouse held out his hand as he said this, quipping, "Look, the dirt's still there."

More: Portsmouth to ask Islington Creek residents and visitors to pay for parking

When he complained his shoes were too tight and hurt his toes, his father said, "But see how shiny your shoes are. Anyone looking at them would think you are well-to-do.'"

He also remembers his family's Victory Garden during World War II, on city-owned land at Pleasant Point.

"I wanted to play basketball with my friends at the Haven School playground (which had the first asphalt basketball court in the city), and Dad would tell me to take a hoe, and go with him to go after the weeds in the Victory Garden. 'We've got to keep those veggies coming,' he said."

Haven School

Living on South School Street next to the Haven School was a big part of Whitehouse's childhood.

He recalled neighbor Walter Woods, who lived on nearby New Castle Avenue.

"He would dress as Santa, open a skylight at his house and throw candy out," Whitehouse said. "The schoolchildren would march up the street to get the candy. We all thought he was Santa."

Woods also made "huge snow sculptures — elephants, tigers, people; geez, was that beautiful."

Whitehouse was in the fifth grade when the Haven School was selected to have "opportunity classes" for handicapped children — the first school in the city to be so designated, he said.

"The children were brought by bus," he said. "I was asked to walk a boy who could hardly talk to the classroom. He would hold onto my arm."

Miss Pray, the kindergarten teacher, was particularly popular.

"She loved children," Whitehouse said. "In kindergarten, we would bring newspapers to lay down on the floor for our nap. We got along OK."

The Whitehouse home at 76 South School St. (which still stands) had no bathroom. There was a flush toilet in the cellar.

"I slept in the attic. It was cold," Whitehouse said. "Every January, my mom gave me $15 for the annual dues for the YMCA (now the site of Jimmy's Jazz & Blues Club on Congress Street). I would go there to play basketball. I would take a shower before I went home. It was the only shower I got."

Rochester romance

Whitehouse enjoyed a long romance with Ruth Kent of Rochester before the two married when he was 29 and she was 28.

"We met in Rochester," he said. "It was at a dance over a drug store and they were playing records. The boys were on one side and the girls on the other. She was sitting there all by herself. Boy, could she dance."

The two had plenty to talk about, he said.

More: Portsmouth Naval Shipyard worker's diaries cover 50 years on Seacoast up to 1907

"I was the oldest of six and she was the oldest of eight," he said. "We talked about our responsibilities, how we had to get on a bike and go out looking for our brothers and sisters if they didn't show up for supper in time. We had a lot in common. We got along."

The two would share 56 years of marriage before her death in 2011, according to her obituary. They had a son and daughter and together built the split-entry home Whitehouse still lives in on Humphreys Court, one street over from where he grew up.

"It took us four years to finish the house," he said. "We'd work all day at our jobs, then go over to the house and work until 11 or 12 at night."

Whitehouse said he always liked to work with wood, and built houses even before taking a job at the shipyard as a carpenter.

"See that paneling," he said pointing to the living room walls. "That's pumpkin pine. It was milled at Rand's lumberyard in Rye."

On to politics, publishing

Whitehouse has lots of stories to share, and plenty of material to draw on. Over four decades, he served as a Portsmouth city councilor for 12 years, on the city school board for 16 years, and spent two years on the Portsmouth Police Commission. He remains a member of the city's Parking and Traffic Safety Committee.

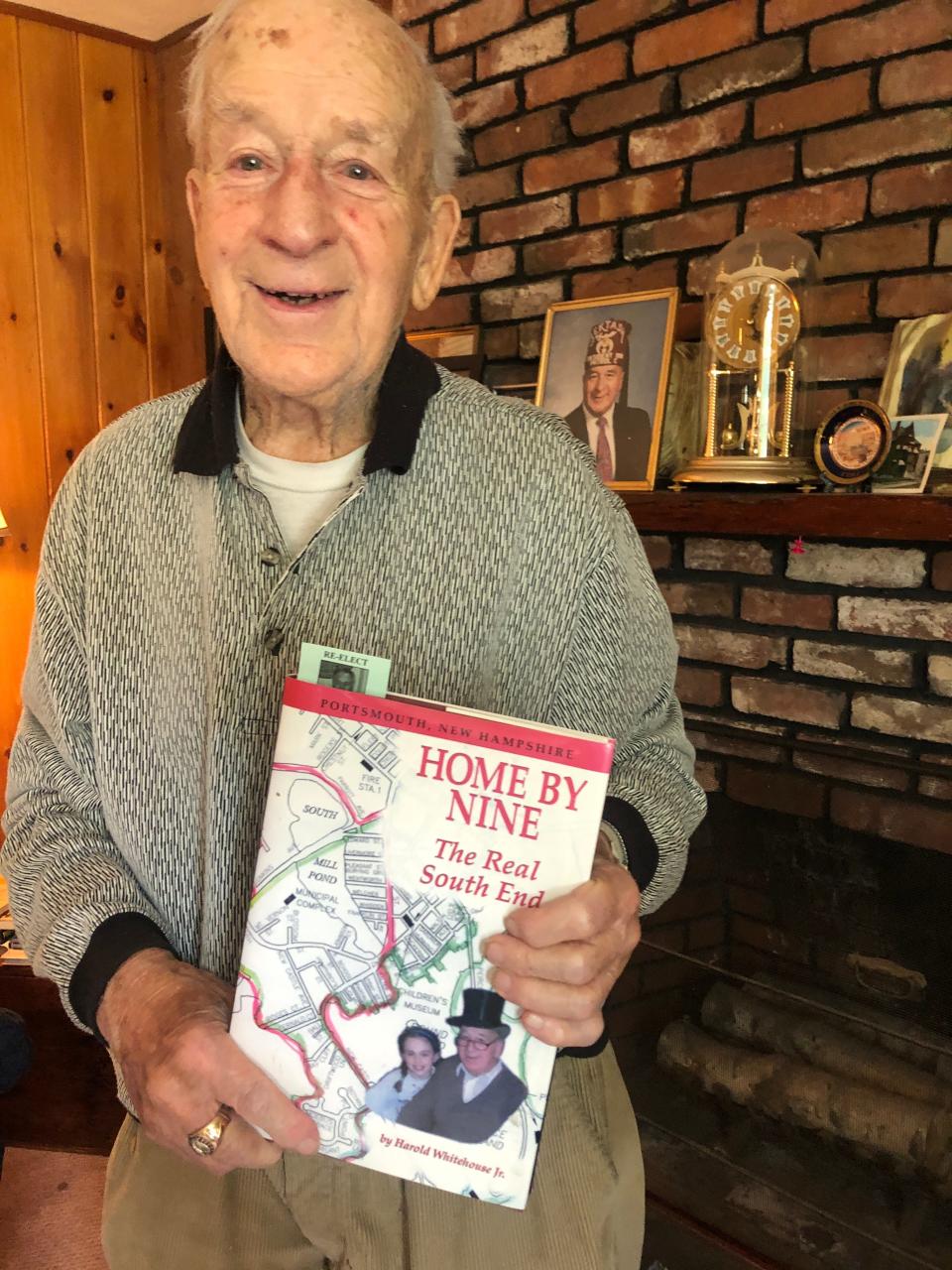

In 2008, he published "Home by Nine: The Real South End" recounting his experiences there from the 1920s to 1970s, when the area was considered a poor neighborhood.

Whitehouse is hoping to reprint the book, and is interested in hearing from anyone who could help him do that. He estimates the cost for 250 copies at around $4,000.

In the meantime, Athenaeum Photographic Collections Manager James Smith is digitizing a number of images that Whitehouse has collected over his lifetime, including family photos and pictures from his tenure at the Portsmouth Herald.

"I'm 94, born July 1, 1928," Whitehouse said at the start of the interview. "I've got memories like crazy."

The Portsmouth Athenaeum, 9 Market Square, is a membership library and museum founded in 1817. The research library and Randall Gallery are open Tuesday through Saturday, 1 to 4 p.m. Masks are required. For more information, call 603-431-2538 or visit www.portsmouthathenaeum.org.

This article originally appeared on Portsmouth Herald: At The Athenaeum: Harold Whitehouse unlocks Portsmouth NH memories