He posed as a doctor and a wilderness expert. Behind the facade was an accused child molester.

Before she recognized him as the man she believed molested her son, Shawna Cleveland handed him a piece of chocolate.

David Menna was pushing his elderly mother in a wheelchair through Tulsa, Oklahoma’s Woodland Hills Mall. Cleveland was passing out samples from See’s Candies. It was Christmastime; the crowds were buzzing.

She bent down to greet the white-haired woman, then stood and caught his gaze. Her heart sank.

It was him.

The man who said he was a doctor.

Who talked of training Navy SEALs.

Who humble-bragged about rappelling with celebrities.

By then she knew he was none of those things, that it was a backstory he’d woven, she believed, to groom her son.

Inside, her brain screamed: “Pedophile! Pedophile!’”

But she couldn’t speak. Few had believed her the last time. Why would now be different? Instead, she ran to the store’s back room and sat with her head in her hands, trying not to throw up.

He introduces himself as 'Dr. Menna'

The first time Cleveland laid eyes on David Menna had been 10 years earlier, in August 2007. She’d taken her son Noah to a meeting of the Young Marines, a national youth organization he had just joined.

The group of a dozen or so boys and girls ages 8 to 18 met every Tuesday, wearing military-style uniforms they were responsible for pressing and starching themselves.

A soft-spoken man with wire-frame glasses sat at the sign-in table, briefcase open, with paperwork for an upcoming camping trip. He introduced himself to her: “Dr. Menna.”

Menna had shown up unexpectedly a few weeks before, at the annual July Fourth veterans appreciation picnic in Chandler Park, on the banks of the Arkansas River. He made quite an impression on the Young Marines’ commanding officer, Terry Funk.

“A wonderful event fell into our laps,” Funk wrote on the youth organization’s website at the time.

The lanky 50-year-old with thinning brown hair had volunteered to give the Young Marines members a lesson in rappelling. To Funk’s delight, Menna had each kid try it right there on the cliffs in the park.

“It turns out he is certified in a number of specialties such as mountain rescue, medical EMSA type rescue, rappelling, etc.,” Funk added a few days later. “He had his equipment in the car.”

Release forms handed out at the August meeting identified the Young Marines as sponsors of the camping trip, along with the “Scouts” – because members of a local Boy Scout troop planned to attend. It was listed on the Young Marines’ website. The Young Marines and Boy Scouts would pay Menna directly for each of their members who wanted to attend, about $150 apiece.

To Cleveland, the trip seemed like a blessing. Because she homeschooled Noah and his three siblings, she always looked for opportunities to introduce them to new activities and kids.

Like the Boy Scouts, the Young Marines is a nonprofit organization aimed at promoting mental, moral and physical development of youth. Its units are run by volunteers, often veterans, who are screened by the National Headquarters. The Scouts, too, had a volunteer selection process that included criminal background checks and references.

Only after things went wrong would Cleveland learn that Menna was not an official, vetted volunteer, and the camping trip was unsanctioned. Only then would she see both the Young Marines and the Boy Scouts turn away.

Cleveland would spend most of the next decade fighting for accountability from Menna, as criminal and civil court cases dragged on and on; from the Young Marines, which introduced Menna to her son and then claimed the man was never their responsibility; from the Boy Scouts, which also denied responsibility for Menna in court.

Menna’s story shows how easily an alleged predator can bounce from one youth organization to another, dazzling parents and boys. The Scouts filed for bankruptcy earlier this year because of mounting liability from thousands of similar allegations, including one against Menna.

He eventually would be formally accused of molestation – in both Georgia and Oklahoma – and both times he’d deny the accusations. Investigations crumbled. Prosecutions floundered. A plea deal was struck. Records were erased and sealed.

That left Menna with a clean background on paper. His name never appeared on any sex offender registry. Every time he was accused, it was as if it was the first.

If he volunteered to lead a camping trip for children today, his record would still look clean.

He markets his outdoor skills to youth organizations

Menna passed himself off as a doctor even though he never held a license. Graduating from Emory Dental School in 1987 was enough to earn him the title, he’d later argue in court.

By the early 1990s, the then-30-something bachelor who lived with his parents had taken up extreme wilderness sports. Rock climbing and caving suited his meticulous nature, according to interviews with dozens who knew him. He turned the basement of his parents’ suburban Atlanta home into a virtual REI store.

It helped that the Mennas lived a few hours from a caving mecca. The geographic region at the intersection of northern Georgia, Alabama and southern Tennessee is home to more than 14,000 caves, carved from limestone bedrock hundreds of millions of years ago by an ancient sea.

Some of those pits resemble the stuff of nightmares, says Dennis Curry, a retired National Park ranger who served as lieutenant of the country’s oldest cave-and-rescue team. Pitch-black, impossibly steep, with slick, pounding waterfalls.

Curry’s team was put through training courses from hell so they’d be able to survive the highly technical work of saving people hundreds of feet below the Earth’s surface.

That’s how Curry found himself approached by Menna.

“This fellow … was going on some caving trips and wanted to learn the skills,” Curry told USA TODAY. “He came to us and my initial impression was: educated, thoughtful, soft-spoken and very clean-cut.”

Menna began to attend clinics for first responders. On one such trip, he stayed at Curry’s house on Lookout Mountain.

By then, Menna was marketing his new skills to youth organizations through a company he called Wilderness Adventures. He gave demonstrations, taught safety skills and volunteered to lead caving and rappelling trips.

“I could never have afforded to pay for what he taught me to do, or the opportunities he gave me,” said Katie Allen, now 41.

After meeting him through a youth services charity, she worked for Menna as a teenager, lugging gear on trips.

Menna worked his way into the groups by skillfully dropping names. One leader would recommend him to another. And so on. Katie remembers helping out dozens of boys.

The time Menna stayed at Curry’s house, he brought two high school aged kids with him. One was Katie. The other, a boy. Menna stayed in the guest room with both teens; Curry and his wife didn’t question the sleeping arrangements.

Only in hindsight, Curry says, did they grow suspicious about why a single man traveled with young people. By the time they saw a news article a decade later detailing Noah Cleveland’s abuse allegations, they’d developed a theory.

“This guy infiltrated his way into our genre because then he could use those skills as legitimacy to get into these kids’ wilderness experience-type programs,” Curry said. “He used us.”

He says he needs to inspect boy for ticks

Noah rode next to Menna in the cab of his dad’s truck headed to Osage Hills State Park for the Labor Day outing in 2007. As the tree-lined hills rose out of the Oklahoma plains, Noah listened while Menna talked and talked.

In the microcosm of a boys camping trip, a leader like Menna is the celebrity, his attention a type of special recognition. As the new kid, Noah soaked it up.

He was slight for an 11-year-old, wiry and lean. The outdoors had always been a hard sell – his analytical nature more suited to books and art. But Noah was trying to keep an open mind and he was particularly interested in rappelling.

He still remembers his excitement when Menna agreed to teach him. They’d just gotten back from a hike when Menna asked what they should do next.

“Rappelling?!” Noah said under his breath.

They spent the next two hours in harnesses, descending the side of a bluff a few yards from the mess hall. Noah could hardly believe his luck. He paid close attention, too, when Menna warned of the danger of ticks.

“That was priority Number 1: making sure there were no ticks on you,” Noah, now 24, told USA TODAY. “And if there was, to come to him.”

A little before midnight that first night, Noah remembers waking up to find Menna in the cabin Noah shared with his dad and other kids. Robert Cleveland, Noah’s dad, had walked up toward the dining hall to make a phone call. Menna said he needed to inspect Noah for the tiny parasites.

He pulled down Noah’s shorts and looked at his genitals, and then said they needed to go to his cabin next door for a more thorough check, according to court records in the criminal case prosecuted by the Osage County District Attorney’s Office in September 2007.

Menna’s cabin was filled with bunk beds and not much else, Noah recalls, save the makeshift exam bed Menna had fashioned out of a sleeping mat covered with a white sheet. That's where he told Noah to lay down, naked.

He ran a flashlight and two fingers across Noah’s skin. It felt like 45 minutes, with Menna asking him to flip over from his backside to his front five or six times, Noah says.

Menna left Noah lying on the mattress while he informed the boy’s father that he had found a tick, according to the court records.

When Robert Cleveland walked into the cabin, he saw his son lying naked on the mattress on the floor, he would later testify. Menna showed him a tick.

Cleveland thought what he witnessed was unnecessary. But, he says, Menna had told him he was a physician, that he personally treated Sam Walton of Walmart fame. So he let it go.

After Noah got dressed, Menna applied bug repellent lotion, starting at Noah’s feet and then sliding his hands up Noah’s shorts, continuing over his genitals, Robert Cleveland would later testify.

Menna also clipped Noah’s toenails.

The next day, Robert Cleveland was called away on a work emergency. He remembers asking other adults to keep an eye on Noah until he returned.

The tick checks continued. Menna stressed their importance at a presentation on survival skills in the mess hall. Noah felt his head tingle. He raised his hand, worried he had more ticks. Again, he was taken to a cabin, this time in the presence of an assistant scoutmaster.

That father would later testify that he saw ticks in Noah’s hair. And then, Menna again went to Noah’s groin. He rubbed the boy’s penis with his finger, lifting it to look in every crevice, according to Noah and notes that his mother later took while preparing for the criminal investigation. Ticks like to get up there, Menna said.

It made Noah uncomfortable. But the presence of adults, and the fact that Menna was so open about it, led him to believe nothing was wrong.

“My dad knows this is happening, (Menna is) a physician ... so it’s got to be OK,” Noah said. “Then you’re lying there like, ‘God, this is taking a very long time.’ ”

'He put bug repellent on me ... everywhere'

At the next Young Marines meeting two weeks later, Shawna Cleveland remembers sitting at a picnic table with other parents when an adult who went on the Labor Day camping trip shared something disturbing: He’d seen Menna massaging another boy, Sam McCormick, while Sam was naked.

Sam was 12 and new to the Young Marines. The trip was his first outing as well. Now 26, Sam remembers waking up one night with a stomachache. Menna was the person to seek out for help, he’d been told. That’s how he wound up in Menna’s cabin in the middle of the night.

Sam says he was looking for Ibuprofen, but Menna clipped his fingernails and toenails, then stripped him down for a tick check.

“He put bug repellent on me; he put that literally everywhere,” Sam told USA TODAY. “He was definitely touching me inappropriately.”

Sam remembers another adult in the room. His presence, he says, was reassuring.

“I didn’t know it was inappropriate,” Sam said. “I didn’t know any better.”

'It was designed to ... make me believe he is someone I can trust'

Hearing Sam’s story recounted at the picnic table, Cleveland was incredulous: How could anything like that happen?

Then the horror began to sink in.

She called her husband at work and repeated what she’d heard. It was like a switch flipped on – she could hear the realization dawn in his voice. That’s when he told her for the first time what he’d witnessed: Noah naked on a mattress. Menna waving a flashlight. The toenail clipping.

It no longer seemed medical. The Clevelands started to believe Noah had been molested.

After years of reliving the details of that weekend in his head, Noah feels certain that all of it was calculated. It was why Menna made them repeat the Scout Oath before every meal. Why he made such an effort to befriend Noah. Why he took pains to create the medical veneer.

“The way he went about it wasn’t designed to make me uncomfortable,” Noah said. “It was designed to do exactly the opposite: To build a relationship and make me believe he is someone I can trust.”

Shawna and Robert stayed up late into the night, talking. That’s when Shawna also started writing. She’d keep it up for the next few years, sometimes full diary entries, other times scribbled reminders, to-do's and Bible verses.

“Writing this helps me get it into my brain and understand it ... there is so much to take in, remember and grasp.”

Within the week, the couple returned to Osage Hills State Park, where they filed a report with the Oklahoma Tourism and Recreation Department and Lt. Mike Vaught, the ranger in charge of investigating crimes in the park.

When they got home, they sat Noah down and explained what had happened.

An expert weighs in

Noah met with a counselor for a forensic interview, part of the criminal investigation. Her ring caught his eye, a cross that turned from red to gold when the light hit it. As a boy raised in the church, taught to look out for God’s will, that seemed meaningful to him.

Shawna Cleveland was impressed by the woman’s demeanor – warm and smiling. But when it was time for Noah to enter the interview room without her, her usually calm kid was very serious. She turned away before he could see she was crying.

“As a parent, you never dream you’ll have to go through something like this. I suppose that is universal to anything horrible that happens to people. It’s almost like a dream.”

The report and Noah’s interview have been sealed at Menna’s request. USA TODAY was able to piece together key details from criminal and civil court records.

According to those records, the forensic interviewer said that Noah told her Menna felt his genitals and put bug repellent on his penis, testicles and buttocks. In her expert opinion, she testified during the preliminary hearing, Noah’s experience was consistent with child abuse.

Another camping trip is planned

On Sept. 21, 2007, three weeks after the trip, Shawna Cleveland woke up hoping for a normal day. She hadn’t yet given up on whatever normal used to mean. Her little girl was turning 9. So, too, was her friend. Cleveland still needed to pick up a gift before the party.

She started making oatmeal for the kids and then woke Noah up. He seemed sad. Burdened by a heavy, invisible weight.

He said he was fine. She rubbed his back. What could she say?

Cleveland knew Menna had another camping trip scheduled for that weekend. She wanted to stop it – the thought of him out in the woods again with young boys chilled her. She urged Vaught, the park ranger, to do what he could.

That evening Vaught called. Menna would be charged with two counts of lewd molestation, one involving Noah, the other Sam McCormick. Cleveland felt like the lieutenant had worked a miracle.

The Osage County Sheriff’s Office arrived at Robbers Cave State Park late that same night and took Menna into custody in view of the campers. He was driven to the county jail, according to a booking report, where he told arresting officers he was a retired investor and didn’t know his Social Security number. He was held for two days before posting $50,000 bail.

Cleveland told her son he had done God’s work. That he’d saved a group of kids that weekend.

Other parents are 'on the doctor’s side'

The rebuke came fast. Cleveland remembers being labeled a troublemaker and blamed for ruining the camping trip. She was told she had humiliated Dr. Menna. And worse, that she was traumatizing her own son. She wrote in her journal:

“Do you know what happens if you allege that a leader in a nationally recognized youth organization is a predator or that you believe your child has been molested? Do you think they would search for the truth? Do you think they would offer you empathy and act concerned or caring? You would be quite mistaken. They will do all they can to protect and elevate themselves and to put you down.”

Today Funk, the commanding officer, remembers hearing about the allegations following the Labor Day trip and reporting them up the chain of command with Young Marines. But more as an FYI, he says, than a serious concern.

Because he heard Noah’s dad was in the room for at least one of the tick checks, Funk told USA TODAY, he assumed the whole thing was bogus, concocted by the boy's parents.

He and the other parents “were on the doctor’s side,” he said. Some continued to go on trips with Menna. “Every other person I talked to thought it was total B.S.”

The civil suit Noah's parents later filed in 2009, Funk said, angered other parents.

“Why would you do this to a little boy if you’re just looking for money or whatever?” he asked.

As Menna’s arrest made local headlines, Cleveland was anxious but pleased. A friend who worked as a victim’s advocate had pushed them to tell their story before someone else did. Plus, it might encourage others to come forward.

In late September, the Bartlesville Examiner-Enterprise ran a story headlined “Tulsa man arrested in connection with alleged molestation at youth camp-out.” Months later, comments began to pop up in the online version.

The first, by a user named DT Lackey in Lawrenceville, Georgia, appeared Dec. 4, 2007: “This is the same person who victimized young boys in the Atlanta, Georgia area in 1993-94. No one here would come forth to accuse him.”

Cleveland's fears that Menna could have done this all before became more real.

“I’m convinced this isn’t the very first child he’s violated and Noah may not be the last.”

'Who wants to stay in Dr. Menna’s tent tonight?'

It had been more than a decade since Dan Lackey met David Menna, but he was still angry when he discovered the news story out of Oklahoma.

He’d gotten to know Menna back in 1993, at a time when tensions were high at home. He and his wife, Lynn, were fighting and failing to hide it from their five kids. They were headed for divorce.

Dan Lackey later wondered if Menna could sense their distraction, if that’s what drew him to them.

They met him at church. Menna’s parents were members of Holy Cross Catholic Church outside Atlanta. Dan and Lynn were, too; they sent their oldest boys to Catholic school and enrolled them in the church-affiliated Boy Scout troop.

Lynn took Matt, then 14, to a presentation by Menna on rappelling. One outdoors trip led to more, so many they blur. Sometimes Dan would join, sometimes it was just Matt or his brother Grant, who was 11.

They got close fast. Menna would often drop by the house. Dan Lackey says he always had a nagging feeling that Menna had an eye on his wife. But the two men were friendly; they once went skydiving together.

“He seemed like a nice guy,” Lackey said. “Lot of big talk. But I thought he was OK.”

Menna brought them presents. He gave Grant a perfectly tailored caving suit. He always made sure the Lackey boys had the best harnesses.

He’d start campfires with homemade “Betty Crocker” bombs – a frosting container filled with shaved magnesium attached to a detonator. He let the boys shoot bowling pins with semi-automatic rifles.

And he showered them with attention.

Lackey remembers that on one trip, when they got to the campsite Menna’s voice “got this kind of excited, higher pitch: ‘Who wants to stay in Dr. Menna’s tent tonight?’ ”

Grant would go on to sleep in Menna’s tent on several occasions. While Menna would act as Matt’s Confirmation sponsor at church, Grant became the favorite. He was athletic and excelled at rappelling and climbing. Menna had Grant help demonstrate skills to different groups – an energetic sidekick.

SUBSCRIBE: Help support quality journalism like this.

Grant found himself going on trips without his dad or brother. That was when Grant says Menna brought out the baby powder.

Menna was insistent, Grant, now 37, remembers. Grant had to put the baby powder on his groin to prevent chafing from the harness. Menna would help.

Grant says he was too young then to understand what was happening to his body. But he remembers Menna masturbated him to the point where he felt the urge to pee; then Grant says Menna expected the same in return.

“He’d say, ‘Oh well you know you’re going to get chafed.’ That’s his big word – ‘chafe, chafe, chafe.’ It’s disgusting,” Grant told USA TODAY. “Then he would make you do it to him.”

Matt vividly remembers the baby powder, too. But he was a teenager with a rebellious streak. He had no problem telling Menna to back off. Grant, still a boy, didn’t know how to make it stop.

Grant would later tell authorities the abuse happened at least twice. Today he says he remembers more than a dozen instances.

It was 1995 when Grant spoke up for the first time. The timing couldn’t have been worse. By then, Dan and Lynn were in the midst of asset and custody disputes.

Menna had become so thoroughly embedded in the Lackey family’s drama that he was called to the stand to testify in the divorce case. He evaded questions and said he didn’t recall nearly 120 times. That testimony offers a rare glimpse into his character.

Pressed repeatedly about his education, Menna said he had a degree in dental surgery from Emory University.

“Do you have any other advanced training or education?” asked Bruce Callner, Dan Lackey’s attorney.

“I do.”

“Describe it.”

“I have done a lot of different course work that is advanced. So, specifically, what would you like to know?”

“Well, all the course work that you’ve done.”

“All the course work I’ve done since then? I don’t recall all of it, sir.”

The judge declared Menna a hostile witness, allowing Callner to ask leading questions.

“Have you ever been a member of the United States Armed Services?”

“No.”

Asked if he had special training in weaponry, Menna said yes, then couldn’t recall what it was.

Menna admitted he didn’t hold a dental license.

Asked whether he felt close to the Lackey children, Menna said, “I felt as though I was being a friend to them.”

No public access to reports helps shield his history

Years later, Noah’s mom, Shawna Cleveland, would learn of Grant’s case through Vaught, the park ranger. He didn’t disclose much, she remembers, except that the allegations were strikingly similar to Noah’s – but worse.

She didn’t know that the Lackeys had struggled to get law enforcement to take Grant’s information seriously, that the response of Georgia’s criminal justice system to Menna’s behavior had foreshadowed her family’s own experience.

In May 1995, Dan Lackey had reported everything to DeKalb police and to the state’s Division of Family and Child Services. The division filed a report with DeKalb police eight days later saying it had received a report from a child alleging: “(W)hile on a camping trip with his Scout Group a worker named David Menna put talcum powder on his genitals. The child stated that Mr. Menna did this to other boys also.”

USA TODAY found three other agencies in Georgia also recorded reports of child molestation against Menna in the 1990s: a second police department, a sheriff’s office and the Georgia Bureau of Investigations. The agencies largely denied requests to review the reports citing victim’s privacy laws, making it impossible to determine whether all of the allegations were related to Grant or if they included other potential victims.

The lack of public access to those reports has helped shield Menna’s history not only from the media, but from parents and youth organizations.

USA TODAY uncovered pieces of the reports, including limited records from a Georgia Bureau of Investigations file. The bureau runs the Georgia sex offender registry and steps in to help with criminal investigations when invited by law enforcement agencies.

The bureau’s file shows that Grant’s case ultimately was referred to the Hall County Sheriff’s Office. As of late June 1995, according to the file, Menna was not licensed to practice medicine in the state of Georgia. His business, Wilderness Adventures, was not registered with the secretary of state’s office.

The bureau opened its criminal case June 30. That same day, a sheriff’s department investigator and bureau agent interviewed a friend of Grant’s, Ben Matthews, who was 12.

“I was terrified of the experience,” Ben, now 38, told USA TODAY. “Basically, I told the GBI investigators whatever it took to get them to leave me alone.”

What Ben didn’t say then was that he had seen Menna rub baby powder on Grant’s groin. After a day of caving in northeast Alabama, the three shared a motel room.

“I was watching ‘Beavis and Butt-Head’ when this event occurred on the bed next to me,” Ben said. “It seemed almost like a routine he and Grant shared.”

After Menna finished with Grant, Ben remembers Menna offering to rub the baby powder on him too. He said no.

It would be years before he told anyone – first a girlfriend, then his parents.

“My voice quakes,” Ben said, “because I do have an immense amount of guilt about this if Dr. Menna was able to pervade and do worse to kids.”

'All they do is to watch out for people like me'

By the time Menna led the camping trips in Georgia, Boy Scouts of America volunteers were required to complete a form. By 1994, volunteers also had to undergo a background check.

Menna was never made to do either.

The Scouts had long been aware of the risk of child abuse within its ranks. Since the 1920s, the organization has tracked thousands “designated as ineligible for participation in Scouting for reasons related to allegations of child abuse” via an internal list dubbed the “ineligible volunteer” files.

Boy Scouts of America told USA TODAY that Menna is on that list today but declined to specify when he was added.

The scouting organization said that it is aware that “in the early 90s, Mr. Menna’s services as a wilderness expert and supplier of equipment for outdoor activities were utilized by at least one Scout troop in Georgia.”

“As soon as the troop was advised that Mr. Menna was not an approved vendor, the troop terminated its relationship with Mr. Menna,” the statement continued. “We are disgusted by his described behavior. It is horrifying that Mr. Menna impersonated a physician to harm innocent children.”

The day after investigators interviewed Ben about Grant, they asked the regional Boy Scouts council for a full list of boys who’d had contact with Menna.

Chuck Keathley, the Scouts’ field services director at the time, told them his office had been contacted about Menna several times, according to the Georgia Bureau of Investigation records.

Keathley was quoted as telling investigators he was “familiar with a conflict that had arisen while Menna was participating with the Boy Scouts in regard to a fabrication that he was a doctor.”

Keith Lawder, who worked with the Boy Scouts at Simpsonwood Methodist Church, told investigators that Menna had taken Scouts on several high adventure outings before parents raised concerns, the bureau records show. He also told them that Menna refused to complete a volunteer form.

“I always had the feeling that there was more to the story than I knew,” Lawder was quoted as saying in the bureau files. “I had concerns but could never find specifics.”

Another volunteer, Wayne Camp, told the bureau Menna found workarounds to get close to young members, violating Scout policy.

“He would call parents and children on the side and get information about trips that we were going to be taking, and he would just show up,” Camp said.

Once, Camp said, Menna turned up at a family campout uninvited. A mother found Menna and four children under a tarp away from the rest of the group. On another outing, Camp said, Menna planned to have a child with asthma stay alone in a room with him.

Lawder and Camp declined multiple requests from USA TODAY for comment, saying they had nothing to add to the bureau’s file.

The report says Camp asked the district executive of Boy Scouts to look into Menna. Eventually Camp was sent an Adult Leader Form for Menna to complete, but he said Menna refused.

Camp told investigators that when he asked Menna to go through Youth Protection training, Menna told him: “All they do is to watch out for people like me.”

Despite the mounting evidence, Grant’s case languished.

In January 1997, nearly two years after the case was opened, investigators rang Menna’s doorbell. A man who fit his description opened the curtain on the glass next to the door, according to the bureau’s file, then retreated into the house.

Then, through his attorney, Menna declined to be interviewed without a warrant.

Six months later the case was closed with no charges filed against him by either agency. Both the bureau and Hall County Sheriff’s Department declined USA TODAY’s request to explain why.

Around that time, Menna disappeared. His parents moved to Tulsa, according to real estate records.

“All of a sudden he was just gone,” Katie Allen recalls.

He had close contact with hundreds of children

The more Cleveland learned, the more frightened and paranoid she became.

She heard about a mom from a neighboring Boy Scout troop who pulled her kids out of the program after unsettling interactions with Menna. And about a scoutmaster who tried, and failed, to get Menna to submit to a background check.

“I feel so sick. Such an icky creepy feeling. Unanswered questions. What was Menna’s goal?”

Then there were the online comments on the news articles about Menna’s arrest. Dozens more appeared suggesting Menna had followed a circuitous path from Georgia to Canada and on to Oklahoma, leaving suspicion in his wake.

He was at Skeleton Lake Scout Camp in Edmonton, Canada, starting in about 1997.

He was at Birch Bay Ranch in Alberta, Canada, in 2000.

He popped up at two churches in Tulsa in 2006.

Cleveland says she heard that Menna had appeared at another Tulsa church a few years earlier, where similar allegations arose concerning young boys. According to her notes, she spoke to the church family several times. They said they wanted to help – but not if it meant pressing charges.

“This is so hard – if no one stands up – there will most certainly be others who will be victims.”

Based on interviews with more than two dozen people who knew him, Menna led outings with Scouts and other youth organizations countless times, putting him in close contact with hundreds of children over the years.

With help from her friend, the victims’ advocate, Cleveland started to understand grooming – how predators build trust with children and parents alike. How they exploit that trust as a cover for their actions. And how it can build a foundation for more aggressive forms of sexual abuse.

She started to worry that Noah might have experienced more than he let on. Or that he’d narrowly escaped it.

There were darker things she would not hear about for years, until USA TODAY reached out to her.

Katie, the outdoor enthusiast who worked with Menna as a teenager, said he never touched her. But as she got older, she began to question Menna’s behavior around the boys.

One trip in particular stands out: Menna insisted on sleeping with a boy about her age in the upper berth of a U-Haul truck they’d rented. She was relegated to a tent outside, by herself.

Thinking back, Katie can remember several times when that same boy stayed in tents with Menna, just the two of them.

That boy, now an adult, told USA TODAY he was abused by Menna over the course of several years beginning when he was around 13. USA TODAY generally does not name individuals who say they were the victims of sex crimes unless they choose to be identified.

The abuse began in much the same way it did with Noah and Grant, the boy said, with tick checks and warnings about chafing. But over the years, he alleges, it progressed to anal sex – and continued until he went away to college.

Noah, 11, identifies Menna in courtroom

As Noah’s case dragged on, his mother questioned whether pressing charges had been the right decision.

Preliminary hearings were held six months after Menna’s arrest, at the courthouse in rural Pawhuska, where toe tips of cowboy boots frequently set off the metal detector. It was a 2½-hour round trip from Tulsa for the Clevelands.

When Noah was called to testify, Shawna was terrified. As an adult, she couldn’t imagine telling a courtroom about the kinds of things her son had experienced, let alone withstanding cross-examination as an 11-year-old.

“He understands that it’s not just for him – but for all the other potential boys who would be Menna’s future victims.”

USA TODAY requested hearing transcripts only to be told a month later that a judge had ordered them sealed during a hearing following that request. USA TODAY later went to court and was granted access before the last of the records were set to be expunged.

At the hearing, Noah was called to the stand in front of Menna and directed to identify the man who abused him.

In thinking back, Noah says it felt like Menna’s attorney was trying to trip him up on the dates and details.

“You can't remember whether it was day or night, but you think it was daytime?” Menna’s attorney, Darrel Bolton, asked.

“Yes, sir,” Noah said.

When Noah explained that he didn’t know he was abused until his parents told him, the defense pounced.

“Do you remember when he told you that?” Bolton asked.

“No, sir,” Noah said.

“You don’t remember? Was your answer that you don’ remember when?”

“Yes, sir.”

Bolton insisted that Menna’s actions constituted first aid and that he was, in fact, a doctor. He also hammered on the fact that Noah’s dad didn’t speak up at the time, that he left the camping trip to handle a work emergency, that he invited Menna to their church. Menna, his attorney said, denied he had done anything wrong.

Shawna Cleveland remembers feeling personally attacked.

“You go to court and you get in trouble because you know, ‘Who told your kid he was molested?’ ” she said. “They make you the bad guy ... and he’s somehow the innocent victim.”

Still more upsetting was the Young Marines’ support of Menna. In the courtroom, Shawna and Robert Cleveland both recall Funk giving Menna a hug, slapping him on the back.

Funk told USA TODAY he doesn’t remember going to court. Asked whether he had any concerns that Menna could have molested children, Funk said, “I don’t know if he did or not.”

“We didn’t ever have to know that because he wasn’t associated with us,” he added.

Sam originally appeared in the case file, too, listed as the victim in one of the molestation counts. But his family moved away and, by August 2008 – a few months after the preliminary hearings – his name had been removed.

Dan Lackey, Grant’s dad, had lost track of Menna for years until he spotted the news story about the Oklahoma arrest. That’s when he contacted law enforcement in Oklahoma to relay the similarities to what had happened with his son.

Lackey emailed Vaught, asking him to let him know if “there is anything we can do to help.” According to criminal court records, Lackey wrote a three-page letter that was provided to the court and Menna’s defense team in January 2009.

Dan and Grant Lackey were added as additional witnesses to the case but never called.

Following the preliminary hearing in the Oklahoma case, the judge ruled that four of five counts could proceed to trial. Multiple continuances, many requested by Menna, pushed the trial date to April 2010 – 2½ years after the Clevelands had filed their police report.

By then Shawna Cleveland was exhausted. The anxiety in the house was palpable. It was hard to keep focus, especially on homeschooling Noah and his three siblings.

“I think Noah felt very much like he had to caretake me,” she says today. “He felt like things were out of control.”

'It is our hope that other young boys be spared'

Just as the jury trial was about to begin, the assistant district attorney came to the family with a plea deal he urged them to take.

It was generous to Menna, Cleveland thought. Far too generous.

Menna would be allowed to plead no contest to one count of practicing medicine without a license. The lewd molestation charges would be dismissed outright. Instead of serving up to 40 years, he’d do two years of probation.

In an email to Shawna, the Clevelands' attorneys said it was apparent the DA’s office didn’t believe it could get a conviction. And without the prosecutors’ support of the case, they didn’t see many options.

Reluctantly, the Clevelands agreed to the deal.

David Keesling, one of the Clevelands’ attorneys, told USA TODAY: “In my opinion this was a guy that skated by on a pretty egregious sex offense.”

The Clevelands did get one demand included in the agreement: Menna would be barred from working with children’s groups during his probation.

“It is our hope that other young boys be spared what Noah and others previous to him have experienced at the hands of a man who derives pleasure in posing as a doctor and placing his hands on the genitals of pre-pubescent boys, all while associating himself with organizations that were created to mold young boys into productive, self-assured gentleman,” they said, according to notes the family took about their statements from the time.

In his own notes, Noah said he prayed that his would be a story of encouragement. He wrote that God had called him to protect other boys.

“One preditor [sic] put away means hundreds of potential victims saved.”

Boy Scouts, Young Marines back away

Amid the criminal case delays, the Clevelands had filed their civil suit against Menna, Funk, the Young Marines and the Boy Scouts of America. They sought damages “in excess of $10,000” for assault and battery, intentional infliction of emotional distress and negligence.

It was during the civil case that the Boy Scouts and Young Marines showed their hand, arguing that Noah’s safety was not their responsibility.

They didn’t organize the camping trip, they said in motions. Plus, Menna was never part of either group, so their failure to register him as an official volunteer or run a background check was not a problem.

In a statement to USA TODAY, the Young Marines said “adults who accompany the youth members to any Young Marines sponsored event or activity are all screened and registered as Adult Volunteers.”

That screening process includes “an application, three letters of recommendation, a national background check, approval by the local unit leaders, and an individual screening by the Headquarters Young Marines,” the statement continued.

But those safeguards did not come into play for the Labor Day trip. The group has emphasized Menna was not a volunteer and the trip was not a Young Marines event.

In a motion seeking to get the case against them dismissed, the Scouts took it a step further. Even if Menna was their responsibility, they said, they had no way of knowing whether he had a propensity for molesting boys.

Georgia Bureau of Investigation records obtained by USA TODAY show that Boy Scout leaders had disclosed child molestation allegations against Menna to law enforcement years before. But Shawna Cleveland and the family’s attorneys say they never saw those records make their way into their case.

Without that kind of concrete evidence on hand, the case against the Scouts was thrown out. The civil case against Funk was also dismissed, the judge ruling he qualified for immunity through a state law that protects volunteers.

That left Menna and the Young Marines as the only defendants.

Menna’s probation in the criminal case ended in March 2012 and the judge granted his request to expunge the case.

By 2014, the Clevelands were running out of steam. The civil case was hemorrhaging time and money. It had been five years since they filed, seven since the ill-fated camping trip. Noah was 18 and finishing high school. Shawna and Robert were formally separated.

They gave up, settling with the Young Marines for $750, with no admission of liability, and dropped the case against Menna.

Shawna Cleveland struggles to move on

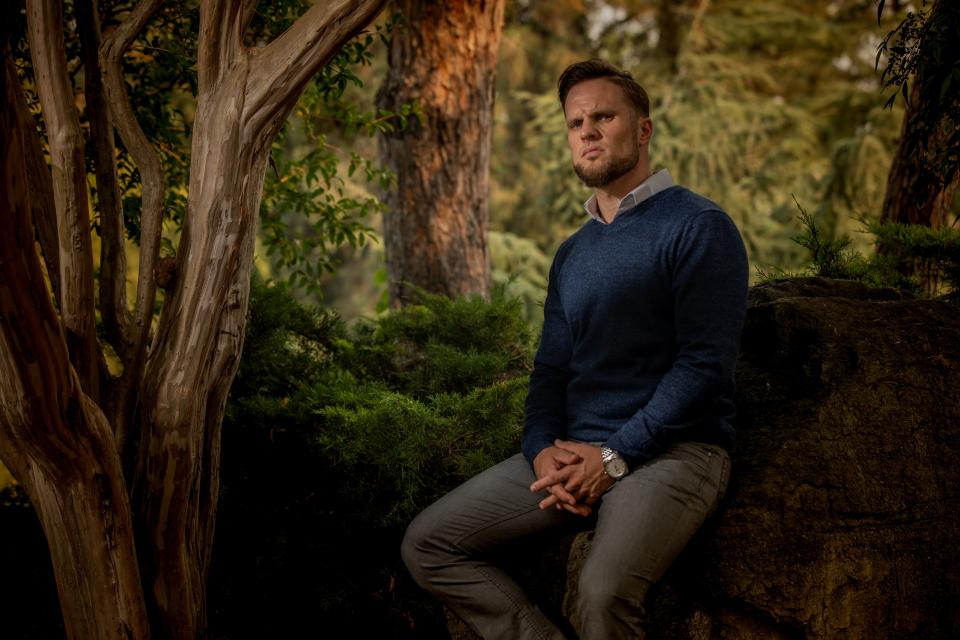

On a recent afternoon, Shawna and Noah sit quietly in a booth at the back of a craft coffee and cocktails place in downtown Tulsa.

They don’t talk about it much anymore, the camping trip that upended their lives. But Shawna wasn’t surprised to hear a USA TODAY reporter had learned of yet another allegation of abuse against Menna from a former Boy Scout in Georgia. Or how it was that allegation that led the reporter to her.

Jacob, who asked not to use his full name, says Menna molested him in 1992 in Georgia, using baby powder on him, too. Jacob didn’t tell anyone until last year, when he saw TV ads from a group of attorneys, Abused in Scouting, representing survivors seeking compensation in the Boy Scout’s current bankruptcy proceedings.

He’s one of the tens of thousands who have come forward ahead of a Nov. 16 deadline for victims to file claims. Many of the allegations of abuse behind those claims date back decades, from older men telling their stories for the first time.

These days, Shawna is eager to support the others who have accused Menna of molesting them.

“How’s Grant doing? Is he OK?” she asks. “Tell Sam he can talk to me. He can call Mrs. Cleveland anytime if he has questions.”

Grant is working as a radiology technician at Stanford University and teaches at a community college, and Sam and Jacob have careers in the military.

Shawna holds it together until Noah leaves for work. He’s waiting tables at a different restaurant while getting an idea for a real estate rental company off the ground.

When he walks out, her emotions break free. The years of guilt and anger and worry. And the tears.

‘From many years ago?’ Menna asks

David Menna is mowing the backyard of the house he shares with his mother in south Tulsa, not far from Shawna Cleveland’s home. She drives by daily on her way to work, often catching a glimpse of Menna’s car in the driveway.

On this day, as a USA TODAY reporter arrives, a school bus drops off a half-dozen kids. They amble to their respective houses, mostly two-story brick with picturesque front yards.

Menna comes around the front to empty his grass bag, shaking clippings into the storm drain. His baggy blue jeans and flannel shirt are dirty from yard work, his hair much whiter than in the booking photo taken more than a decade earlier at the Osage County jail.

A reporter’s question about the sexual abuse allegations seems to strike him as surprising – but not out of left field.

“From many years ago?” he asks.

After explaining that USA TODAY had heard multiple allegations – claims of abuse that span at least 15 years – his stare widens.

“I don’t think there’s much of a story there,” he says, and goes back inside.

Handwriting in the photo illustration and throughout this story is drawn from Shawna Cleveland's journals and notes. Design by Mara Corbett.

Contributing: Brett Murphy of USA TODAY and freelance reporter Andrea Eger.

Cara Kelly is a reporter on the USA TODAY investigations team, focusing primarily on pop culture, consumer news and sexual violence. Contact her at carakelly@usatoday.com, @carareports or CaraKelly on WhatsApp.

This article originally appeared on USA TODAY: How an accused predator gained access to Boy Scouts, Young Marines