The Post-COVID Home: How the Pandemic Has Made Us Rethink Everything

Illustration by Yeji Kim

Once or twice a day, I'd lean headfirst out of my living room window, extending my neck up towards the sun, as far as it could reach. Given that I live on the sixth floor of my Queens apartment building, that was probably a little too far. I doubt it was ever for more than 30 seconds at a time, but it felt like a mini-vacation-even on days it was raining.

It was May 2020, and I was afraid to think about how long it would last: both the COVID-19 pandemic in general and my own symptoms. The shortness of breath, body aches, chills, and tremors (along with basically everything else on the list) had started on April 2, and by mid-May it was clear I'd be sick much longer than the 14 days we were told the illness would last.

Sometimes, on sunny days when I could muster up the energy, I'd crawl out of my kitchen window onto the fire escape. Each time, as I hoisted one leg after the other out onto the open steel grating, I'd recall my grandmother's stories about how she and her siblings would take turns sleeping on the fire escape of their Brooklyn tenement apartment during the hottest days of the summer in the mid-1920s.

As a child, everything about that scenario terrified me, but here I was, close to a century later, doing something similar. If anything, it somehow made me feel safer. No, not the part where I'm six stories up, putting my life in the hands of a 93-year-old fire escape-more like feeling comforted by the connection to my grandmother.

Getty Images

Part of our concept of "home" is as a place of refuge from the outside world. It's somewhere we can feel both physically and psychologically secure. "Homes originated as a place for us to feel safe," says Susan Clayton, PhD, the chair of the psychology department at the College of Wooster and an expert in environmental psychology. "Their primary function is to protect us from predators, weather, and other people."

This also means that if we don't feel safe at home, it's hard to find another place where we can get that feeling of security, Clayton explains. "The physical protection that a home provides is very important, but also important is the sense that we have some control over the home: we get to make choices about who or what enters; we get to personalize the space in a way that reflects our identity," she adds.

When the COVID-19 pandemic hit in the spring of 2020, the function of our homes as a place of protection became evident in a way that it hadn't yet been in our lifetime. As the SARS-CoV-2 virus made its way around the world-and with no treatment or vaccine in sight at the time-it put us in a situation that was, in some ways, similar to the one people faced more than a century ago, during the 1918 Flu Pandemic.

In both cases, there was so little people could control, with the exception of what went on inside their own homes. From determining who is permitted to cross the threshold, to implementing our own sanitation and hygiene protocols (i.e., cleaning every surface), to surrounding ourselves with certain colors, fabrics, and decor, the COVID-19 pandemic once again made our homes crucial tools for maintaining our physical and mental health.

In addition to the privilege of having a job that allows me to work from home, I've also spent the last year feeling grateful for my apartment itself. The three large windows (including the one that leads to the fire escape) bring in a significant amount of sunlight-especially in a 400-square-foot studio. Two of the three remain open, or at least cracked, year-round: something made possible by one small-but-aggressive radiator, powered by my building's steam heating system.

If it sounds as if my apartment was designed specifically for the events of the past year-especially being well-ventilated yet still quite warm throughout the coldest days of winter-that's because it was.

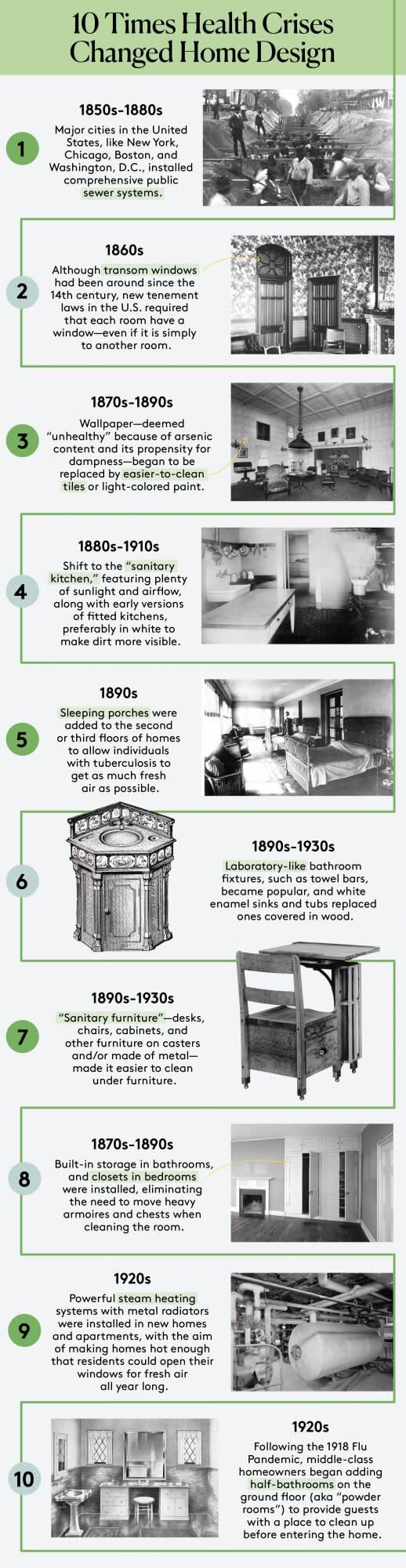

Julia Bohan Upadhyay / Photography credits (from top): Getty Images (3), Library of Congress (2), Getty Images, Library of Congress (3), Getty Images

How Past Health Crises Influenced Home Design

When construction on my apartment building began in 1927, only seven years had passed since the final wave of the 1918 Flu Pandemic hit New York City in the spring of 1920, and it would be another year before the discovery of penicillin. At this stage, the city had already experienced a noticeable decline in deaths from conditions like tuberculosis since the end of the 19th century. This was thanks, in large part, to the implementation of a wide range of public health measures, improved water and sanitation services, and a better understanding how infectious disease spreads and the role of home design in its prevention.

Remember my compact-yet-mighty radiator that allows me to keep my windows open all year so I have a continuous source of fresh air and ventilation? While certainly convenient, it's not there by coincidence. The use of overbearing steam heat was a relatively common feature of structures built following the 1918 Pandemic and throughout the 1920s-not only in New York, but also in other populated cities with harsh winters, like Boston, Cleveland, Philadelphia, and Chicago. By allowing windows to remain open, even during the coldest months of the year, steam heat improved the airflow in buildings, helping to prevent airborne diseases.

And that's just one of many examples of home design innovations, advancements, and trends prompted by health concerns throughout U.S. history. Here are four more.

Illustration by Kailey Whitman

Transom Windows

The idea that fresh air and ventilation are crucial in reducing the spread of infectious disease actually predates germ theory, or the understanding that microscopic organisms known as "germs" invade a person's body, making them sick. Prior to the discovery of germ theory at the end of the 19th century, it was thought that people fell ill after breathing in noxious vapors or foul-smelling "bad air" known as miasmas. As a result, a well-ventilated home was seen as one of the most effective ways to protect yourself and your family from this disease-causing air.

While "fresh" outdoor air was the ideal, many urban working class housing options-like narrow row houses, tenement apartments, and shotgun houses-may have only had one exterior window in the entire home, making any type of cross-ventilation next to impossible. So to help improve airflow, interior openings, known as "transom windows" as early as the 14th century, were installed directly above doors opening into a hallway or between two rooms.

They were also referred to as "tuberculosis windows" when they became legally mandated under New York City's Tenement House Act of 1867 in an attempt to counteract the rapid spread of the respiratory disease in the city's overcrowded neighborhoods. Though the law stipulated that each room in a tenement was required to have a window, it didn't specify that they had to be exterior windows, so building owners took the easy way out, creating interior windows instead.

"The whole premise of ventilation is to maximize the outdoor air that's being brought into the interior environment," explains Dak Kopec, PhD, an associate professor of architecture at the University of Nevada, Las Vegas and an expert on the intersection of health and design. "And the fundamental goal of using ventilation to prevent tuberculosis was to flush out the bad air by bringing in good air." This goal became more realistic in New York City after the passage of an updated tenement law in 1901, which required each room to have at least one window with access to outdoor air.

From Wallpaper to White Paint and Tiles

When you picture the parlor of a Victorian-era home, there's a good chance it features colorful, patterned wallpaper. Apart from simply being stylish, the busy designs also served another function: to mask the flies so prevalent in homes at the time, as well as the stains they left behind.

But by the 1870s and 1880s, there were two separate yet intersecting wallpaper trends prompted by health concerns, according to Bo Sullivan, a historian specializing in American residential architecture and decor from 1870 to 1970 and owner/founder of Arcalus Period Design in Portland, Ore. The first was the growing awareness-thanks, in part, to the 1874 book Shadows from the Walls of Death-that the arsenic used in distemper paints for wallpapers was slowly poisoning a room's occupants.

The second was an ever-increasing focus on the "unhealthiness" of dirty and sometimes damp layers of uncleanable wallpaper. "Parallel to developing awareness of germ theory and the increasing fear-and even panic-of consumers around this general subject about which little was understood, manufacturers began printing wallpapers in oil-based inks and varnishing the surface of the papers so they could be cleaned," Sullivan says. "These were called 'sanitary' papers and were used primarily in kitchens and bathrooms, often in patterns that evoked tile, sometimes referred to as 'tile' papers."

Getty Images From the 1870s to the 1890s, patterned wallpaper was slowly replaced by white painted walls.

But with the arrival of the "sanitary craze" in the early 20th century, there was another health-related shift in Americans' home decor preferences. This new obsession with cleanliness meant that it was no longer acceptable to rely on busy patterns to mask the unsightly grime and fly stains covering the walls. Instead, the walls of a home should be light in color-white, ideally-to make it easier to spot and then clean any dust and dirt, which was believed to contain illness-causing germs. While walls painted light shades could be found throughout a house, the shiny, white subway tile used to make the walls of kitchens and bathrooms look as sterile as possible is the most prominent holdover from this period.

Linoleum and Tile Flooring in Kitchens and Bathrooms

When wealthy households began getting indoor plumbing in the late decades of the 1800s, the bathroom had to be created out of an existing room, which typically had wood floors. Installed before the sanitary craze really took off in the early 1900s, these bathrooms featured sinks, bathtubs, and even toilets encased in wood as a way to disguise their actual purpose. But once people had a better understanding of germs and sanitation, they started replacing the wooden fixtures with ones made of easier-to-clean materials, like the enamel-coated cast iron introduced by the Kohler Company in 1883 as a way to make their products "superior, clean and hygienic." Wood floors had to go too.

Recognizing that the natural crevices in wood floors could collect germ-carrying dirt and dust, the flooring of choice in bathrooms and kitchens became smooth, nonporous tiles, along with a relatively new material called "linoleum." Thick, waterproof, and durable, linoleum also replaced its predecessor, oilcloth, which had been around since the 1700s.

Like many other household products of the early 20th century, linoleum flooring was marketed as a way to protect your home and family from dangerous pathogens. For example, a 1914 newspaper ad for the Sanitary Composition Floor Company describes its flooring as "fire-proof, waterproof, [and] germ and vermin-proof," claiming that it "will outwear two wood floors."

Updated Kitchen Design

Though nearly all homes had some version of a kitchen long before the obsession with cleanliness and home hygiene began, the awareness of germs-including the ones that could come from or be spread by food-meant big design changes for the room. Like the other parts of a home, ensuring that a kitchen got plenty of sunlight and ventilation through strategically placed windows became increasingly important. In fact, according to an April 1915 article in The Craftsman magazine, architects of that time were designing new homes with kitchens located at the front of the house to maximize exposure to natural light and fresh air.

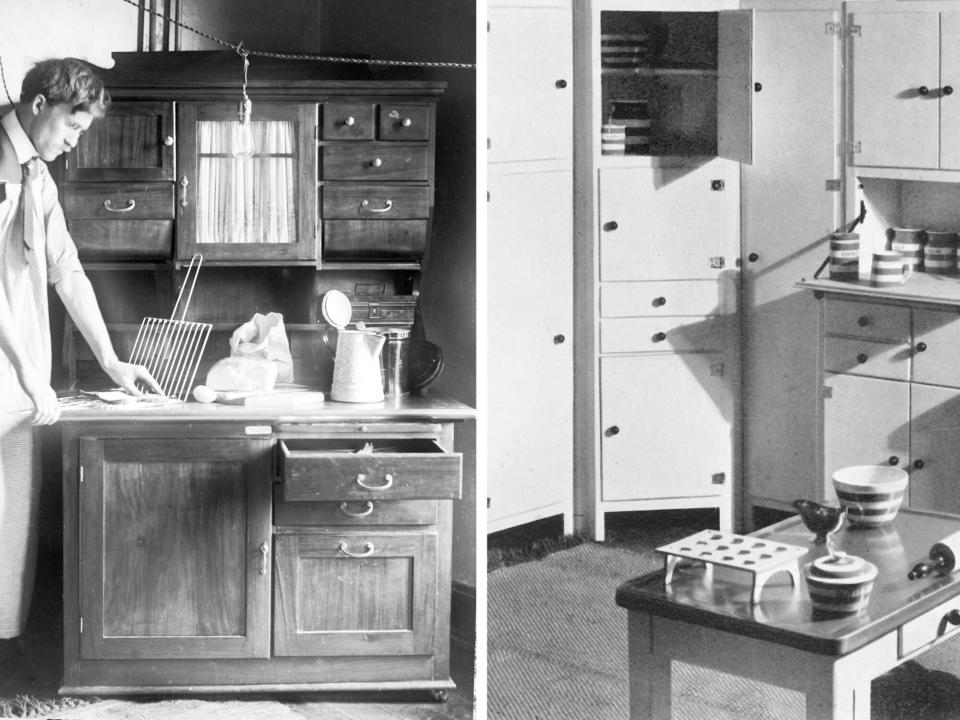

Getty Images In the early 1900s, separate kitchen cabinets were swapped out for easier-to-clean built-in cabinets.

The new focus on sanitation also meant the rise of the "fitted kitchen." Instead of having several pieces of freestanding furniture, the cabinetry, storage, sink, and eventually appliances were incorporated into a single custom-built unit that was attached to the wall. Though fitted kitchens became standard after World War II, earlier versions known as "sanitary kitchens"-which often included a state-of-the-art Hoosier Cabinet-were introduced in the first few years of the 20th century. Built-in kitchens were easier to clean, as they eliminated the need to move heavy pieces of furniture to clean under, around, and behind them.

This modern kitchen design also incorporated many of the same upgrades as the bathroom, including tile or linoleum floors replacing wood floors, tile or painted walls in place of wallpaper, and sinks made from white enamel instead of stone- or metal-lined wooden boxes. Similarly, white was the recommended color for kitchens, as it was considered "a most sanitary as well as attractive style," according to the same 1915 article in The Craftsman, because of its ability to show the dirt that needed to be cleaned. "There was a 'laboratory'-type quality to early-20th-century bathrooms and kitchens that still plays very well today with both the industrial trend and the preference for white minimalism-both looks with DNA in the sanitary movement," Sullivan explains.

Inside the Post-COVID Home

I had COVID twice, and both times I felt weak, fatigued, and dizzy, especially during the first three weeks of each infection. The walk from my bed to the bathroom was only a few steps, but it would leave me out of breath. Being unsteady on my feet meant that each trip to get food or water involved holding onto both sides of the galley kitchen for support. When I needed to sanitize the kitchen or bathroom, I didn't have a lot to wipe down.

After years of participating in the time-honored New York tradition of complaining about the size of your apartment, I realized how fortunate I was to somehow end up in the ideal space for a person living alone with COVID. And it's not just me: spending more than a year constantly inside our homes has prompted a lot of people to reconsider their decor and design choices, as well as what they need and want in a place to live. Here are a few examples of how the pandemic has changed, or is likely to change, our homes.

Top Priorities for Buying, Renting, and Renovating

Spending so much time at home this year has given people plenty of opportunities to rethink the qualities they look for in a home-whether they're buying, renting, or renovating. For example, younger prospective homebuyers (between the ages of 18 and 43) have experienced a shift in priorities, with 68 percent saying safety and security are more important to them now than before, and 60 percent indicating that having outdoor space is more valuable than indoor square footage, according to Bank of America's 2021 Homebuyer Insights Report.

And although people may enjoy watching home renovations on TV, the pandemic has made the option of a move-in ready house more appealing. According to a 2021 survey from Buildworld of 1,200 respondents from the U.K. and the U.S., the participants said they're more than twice as likely to purchase a turnkey home than a fixer-upper this year. Meanwhile, a 2021 survey from Cinch Home Services found that 54 percent of current homeowners plan to renovate at least part of their home this year, with bathrooms and kitchens at the top of the list.

Not surprisingly, renters are now most drawn to features that would have improved their quality of life during the pandemic. Outdoor space, a parking spot, and in-unit laundry were top on the renter wishlist, according to a report from Zumper comparing the most-searched-for rental amenities in December 2019 and December 2020.

Illustration by Kailey Whitman

In-Demand Office Space

In a year when working from home went from a perk to a necessity for a lot of people, the home office made a major comeback. Once considered a must-have for any serious professional, rooms originally designed as offices were frequently repurposed for other functions, and left out of plans for new builds altogether. But a December 2020 survey from CouponFollow found that remote workers once again see the value of some version of a home office, with 75 percent of remote employees reporting that they have invested their own money on a dedicated workspace, spending an average of $572.

Getty Images

The Debate Over Open Floor Plans

After decades as the default home layout for renovations and new construction, people began to turn on the open floor plan even before the pandemic. But style preferences aside, the necessity for our homes to suddenly function as offices and schools during the pandemic highlighted many of the shortcomings of open concept houses.

That's why Ted Roberts, style and design expert for Schlage, thinks we'll see more flexible-use spaces moving forward that blend smaller enclosed spaces with open areas that can be reconfigured as needed. "Space needs to be adaptable and storage and compartmentalization will be key," Roberts says. "Both built-in and furniture storage are options to avoid clutter. Sliding barn doors and pocket doors can quickly change an open space to one of privacy."

And we can't forget about the noise. Sounds from every conference call, virtual classroom, Zoom music lesson, plus dogs barking and pots and pans clanging in the kitchen, carry throughout an open floor plan. Both Roberts and Kopec see this as a major strike against the cavernous layout.

Finally, open-plan homes give us something to think about in terms of airflow. On the one hand, Kopec says that this style can help ventilation throughout the house. On the other hand, if someone in your household ends up getting sick with something contagious, you're not going to want that particular air circulating. "If you can keep someone with an illness relatively confined to a space, and you can keep that space directly ventilated, you may be able to help contain a virus and decrease the probability of it making other people sick," Kopec explains.

Getty Images

Multigenerational Living Spaces

Though many households were multigenerational before the COVID-19 pandemic, more people opened up their homes to elderly parents or grandchildren over the past year. A recent study by Generations United found that the number of multigenerational households in the U.S. (aka those with three or more generations) has nearly quadrupled in the past decade, and 6 in 10 reported that they started or continued living together because of the pandemic. This shift is also reflected in homebuying trends: data from the National Association of Realtors shows that 15 percent of homebuyers purchased a multigenerational house in 2020, an all-time high since 2012.

"We've become a diverse society, and today's homes need to satisfy families with differing ages and health issues," Roberts says. "This impacts both the nature of our spaces and the amenities within them." According to Roberts, examples include making sure rooms and hallways are well-lit for safety purposes, and factoring in some level of privacy for different members of the household. Other homebuying trends for 2021 call for design features that can accommodate individuals of all ages and abilities, such as the demand for curbless showers and more accessible kitchens with wider pathways that can accommodate children in strollers and those in wheelchairs.

Getty Images

The Bathroom as a Sanctuary

While the bathroom has long been at the center of sanitation in the home, during the pandemic, it also became an escape. "Bathrooms, for most of us, are the only place we can get privacy," explains Jason Keller, marketing manager for the design team at Kohler. "And while we realize that self-care can happen anywhere, the bathroom continues to be the hub for wellness."

"With everyone at home all the time and dealing with the stress of the past year and a half, it seems that consumers are looking to create a healing space within the home," says Mittal Shah, the leader of brand activation for Grohe US and LIXIL Americas. According to Keller, Kohler has been seeing its customers prioritize aspects of bathrooms once considered luxuries, like steam showers.

According to the 2020 Houzz Bathroom Trends Study, which was conducted during the pandemic in June and July 2020, two in five homeowners surveyed said they use their bathroom to rest and relax (41 percent). In the bathtub versus shower debate, the results were split evenly: 55 percent reported enjoying baths, while 54 percent said they preferred long showers. While more homeowners chose to forego the bathtub in 2020 compared to 2019, those who upgraded theirs opted for a luxurious freestanding tub (53 percent). For renovators who upgraded their showers, rainfall and aromatherapy shower heads were popular choices. Not planning a full bathroom remodel in the near future? You can still upgrade your current shower by installing a new shower head.

Getty Images

The Kitchen as the Household Headquarters

After spending so much time at home, people began to realize that most rooms in the house would have to serve multiple functions, including the kitchen. That's why a spokesperson for the Design Studios at Meritage Homes says the company is expanding both its kitchens and kitchen islands to accommodate more cooking and eating at home.

In addition to seeing more at-home cooking, many kitchens have also doubled as home offices and classrooms. Though not every home has the space for an island, Meritage Homes predicts that they'll see an increase in popularity. "Kitchen islands also serve many other functions where the additional size is appreciated, such as a makeshift work environment."

As the kitchen now serves several functions, homeowners are looking for storage solutions that will help this room do it all. According to the 2021 Houzz Kitchen Trends Study, cabinets with built-in specialty organizers, trays, and drawers are on the rise. The most popular options: cookie sheet organizers (48 percent) and spice organizers (39 percent). "We're seeing an increase in the amount of cabinetry added in renovations, and more homeowners are reaching out to professionals on Houzz for help making their kitchens work better, most often within the same layout and square footage," said Liza Hausman, vice president of industry marketing at Houzz. For now, savvy homeowners are getting creative with space and storage to maximize their kitchens, but designers predict that the pandemic will have numerous effects on kitchen design in the years ahead, influencing everything from countertop materials to touchless appliances.

Touchless Everything

Back in the early 20th century, during the so-called "sanitary craze," people suddenly looked at their homes in a new light: specifically, one that made them see all the places that could contribute to the spread of germs. The COVID-19 pandemic, especially during the first few months, had a similar effect, with everyone suddenly concerned about disinfecting everything that came into their home.

And while touchless faucets and toilets have long been a staple in public restrooms, the feature became significantly more popular in homes in 2020. "The emphasis on health and wellness brought on by the pandemic has accelerated the changing perception of the home," Shah explains. "COVID-19 has made everyone more aware of germs that can linger on surfaces." In fact, since the pandemic started, she says that Grohe has seen a substantial uptick in searches for the word "touchless" on their website.

A survey conducted by The Harris Poll on behalf of Kohler in June 2020 found that even early on in the pandemic, 85 percent of participants said they were more interested than ever in touchless products in the bathroom, while 67 percent of parents with children under the age of 18 said that touchless kitchen faucets are a "must-have" for making their home healthier. And the touchless options go beyond sinks and toilets, including touchless and voice-controlled appliances, such as refrigerators, ovens, and dishwashers.

Getty Images

Lush Landscaping and Gardening

With the challenges the pandemic has presented and the extended time at home, many people want to make their home feel more like a retreat, and that includes in their outdoor space (if they're fortunate enough to have one). According to Rose Kemp, an associate at RE/MAX Town Centre in Orlando, Fla., people are looking for "landscaping styles that offer peace and tranquility-a place to relax and possibly even meditate after a long workday at home."

For those with backyards, patios, or decks, creating an inviting outdoor space has become a new focus for many. According to a 2021 survey by the International Casual Furnishings Association, 78 percent of those with outdoor space made upgrades during COVID-19, including planting trees (38 percent) and adding a garden (29 percent).

"I have also noticed that vegetable, fruit, and herb gardens are especially popular among younger generations," Kemp says. The concept of the "victory garden," which has its roots in World War I when community vegetable gardens sprang up across the country, made a comeback during the pandemic. With more time at home and at a moment when even a trip to the grocery store was complicated, homegrown vegetable gardens surged in popularity and online seed sales soared last spring and summer. The motivations for gardening may have changed over the past year, but the interest in gardening and homegrown food has continued into 2021.

Getty Images

A Point of Entry

Over the past year, many people have reworked the entryway to their homes to accommodate their new pandemic lifestyle. Even those without a dedicated mudroom or entryway likely have at least some sort of sanitation station set up near the door where they keep their face masks, hand sanitizer, disinfecting wipes, outside shoes, and anything else that has become a pandemic necessity. And now that we've gotten used to doing this, some people will probably continue at least some of these hygienic procedures once we're finally on the other side of all this.

At Meritage Homes, for example, the company's design team has expanded the entryways in their new floor plans to accommodate the additional cleaning and disinfecting of people and products coming into and leaving the home. "It allows a space for a bench, coatrack, or countertop to drop whatever you're carrying and disinfect it if you feel the need to do so. This creates a more defined 'drop zone.'" There has also been increasing interest in placing a sink in a mudroom, garage, or entryway to give people a place to wash their hands as soon as they enter the home.

Have We Learned From Our Past?

With the exception of the significant technological advancements made in sanitation over the past 100 years, many of the changes to home design prompted by COVID-19 mirror responses to pandemics and epidemics of the past, including influenza, tuberculosis, and cholera. But at this point, it's unclear whether these home hygiene trends will stick around this time. That's because we don't have the best track record when it comes to maintaining these sanitation standards once a new treatment comes along.

Remember bathrooms with wall-to-wall carpeting and those fuzzy toilet seat covers? They rose to popularity in the 1950s-not long after the widespread use and availability of antibiotics-and could be found in homes throughout the country well through the 1970s.

While history might suggest that recent health-related home trends could quickly be forgotten, what about changes that also improve our quality of life? We've been quarantined in our homes for more than a year, and during that time we've certainly made hygiene-related tweaks, but we've also had the opportunity to really exist in our spaces and adapt them to make our new homebound lifestyle more tolerable.

We might not keep our voice-controlled appliances solely because they reduce the spread of germs-but they also make it easier to cook dinner while taking a Zoom call. And once we've experienced cooking a meal using vegetables from our garden and enjoyed that meal in our beautifully landscaped backyard, how can we go back to undervaluing our outdoor space? Plus, as more companies adjust to long-term work-from-home or flexible schedules, our new home offices may continue to be worth the square footage they command.

Odds are, the legacy of this pandemic's effect on home design will be long-lasting, with a greater focus on features that improve both our physical and mental well-being, making time spent at home more fruitful, relaxing, and healthy. Of course, only time will tell.