A Post-Filibuster World Would Be a Nightmare for Progressives

With astonishing speed, it’s become conventional wisdom on the left that the filibuster must go.

Having seized full control of the White House and Congress — but just barely — many Democrats naturally see the Senate’s 60-vote threshold as an inconvenient obstacle to passing their agenda. They call it a “Jim Crow relic” for obstructing voting rights bills and hope to topple it like a Confederate statue.

But progressives pushing to end the filibuster are suffering from a bad case of amnesia. The past three decades, in fact, are filled with moments when the filibuster prevented Republicans from pushing through legislation that would have made America a far darker place.

The Democrats now in power should weigh the present opportunity against future peril. Republicans have their own ambitious agenda which they will be delighted to enact over the helpless cries of a filibuster-less Democratic minority as soon as they can. A tour of recent history offers some stark examples of what that might look like.

In 1995, it’s not much of an exaggeration to say, the filibuster saved the regulatory state.

The previous year’s midterm elections under President Bill Clinton was a bloodbath for Democrats. Republicans gained 54 House seats and nine in the Senate, handing them majorities in both chambers. The GOP-controlled House, led by hard-charging Speaker Newt Gingrich, immediately passed an avalanche of bills to fulfill the so-called Contract with America. The president’s veto pen provided some defense, but Clinton, chastened by his party’s electoral defeat and repositioning himself toward the center for his 1996 reelection, was reluctant to veto many GOP bills. The sturdiest backstop against the Gingrich juggernaut was the 47-member Senate Democratic minority caucus armed with the power of unlimited debate.

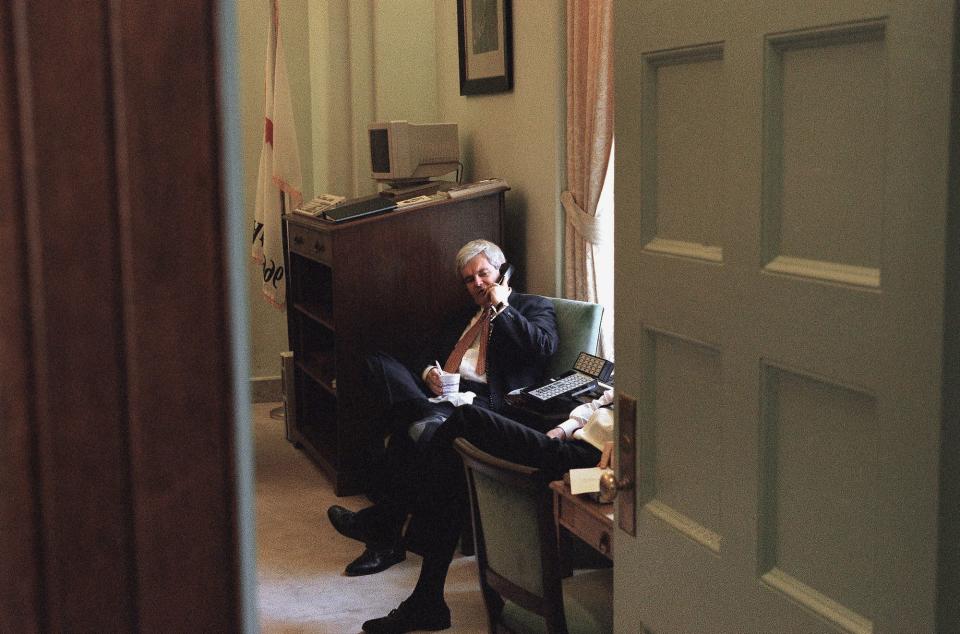

A key GOP target at that time, as it is now, was the nation’s regulatory regime. A GOP bill to cripple the ability of agencies such as the Food and Drug Administration, the Environmental Protection Agency and the Occupational Safety and Health Administration to issue public health and safety rules came to the Senate floor. Majority Leader Bob Dole sought to end debate three times, but the Democratic minority held firm, and each cloture petition fell short, the last by only two votes. The bill failed.

In 2005, President George W. Bush, emboldened by his reelection and backed by healthy GOP majorities in Congress, set out to partially privatize Social Security. The proposal would have transformed the government’s social safety net for elderly Americans into a stock market investment. Solid opposition by the 45-member Democratic Caucus stopped the proposal in its tracks, even before it came to the Senate floor. Just three years later, the global financial crisis erased trillions of dollars from Americans’ private retirement savings — but Social Security checks went out as scheduled.

Proponents of filibuster abolition correctly point out that the filibuster has been sometimes deployed to block noble bills such as the mid-20th century civil rights legislation. But obstruction by the minority can eventually be overcome by popular will and presidential leadership, as eventually occurred with civil rights. In contrast, an unchecked majority can wreak havoc.

It isn’t necessary to look as far back as 1995 or 2005 to see what life would be like without the filibuster. Just remember the past four years of presidential nominations.

In late 2013, Democrats, frustrated with the slow pace of confirmations for President Barack Obama’s nominees, deployed the so-called nuclear option by unilaterally changing the rules to allow for simple majority confirmation of executive branch and judicial nominations, except for the Supreme Court. In the short term, it paid off: they were able to win confirmation of many Obama nominees in the remainder of that Congress, before the GOP regained the Senate majority in the 2014 midterm and ground the nominations process to a near-standstill.

But in the long term, it was a disaster for Democrats.

When Donald Trump became president in 2017, he had free rein to nominate and win confirmation of virtually anyone, including some Cabinet and sub-Cabinet nominees whom Democrats considered plainly unqualified or repugnant. Moreover, he had a clear field to repopulate the federal judiciary with young Federalist Society-blessed nominees. Altogether, Trump appointed a record 174 district court judges, 54 courts of appeals judges and three Supreme Court justices in only four years.

It is laughable that commentators gave Trump and Majority Leader Mitch McConnell “credit” for the “accomplishment” of confirming so many judges. It is no accomplishment to shoot fish in a barrel. With no filibuster to give the Democrats leverage, all McConnell needed to do was schedule votes and the outcome was inevitable.

When Democrats attempted to muddle McConnell’s schedule, he brandished the precedent of their 2013 rules change to justify a retaliatory strike by unilaterally changing the rules to speed nominations, including to the Supreme Court. Most disturbingly, McConnell was able to ram through Amy Coney Barrett’s confirmation to the high court — in blatant disregard of his blockade of Merrick Garland’s appointment — because the filibuster was no longer available for nominations.

One reason McConnell had so much time to schedule votes on judicial nominees is that he had few legislative items with any hope of enactment — and for that, Democrats largely have the filibuster to thank. Republicans wanted to defund Planned Parenthood and limit protections for undocumented immigrants, among many other priorities. The reason those goals were not realized was the legislative filibuster. For example, a proposal to impose stiff restrictions on abortion had majority support in a 2018 vote, but failed to advance when 46 senators said no.

In those years, Trump was as frustrated by the filibuster as any Democrat is today. He repeatedly called on congressional Republicans to nuke the legislative filibuster and called them “fools” for not doing so. Yet McConnell and his GOP colleagues did not yield to presidential pressure.

One persistent argument for the rules change among Democrats is that “we might as well do it — because if we don’t, they will.” But from 2015 to 2020 Republicans had ample opportunity to “go nuclear” for legislation and they refrained. It was during this period that a bipartisan group of 61 senators, including then-Senator Kamala Harris, signed a letter defending the legislative filibuster.

Be assured, McConnell would not refrain again if Democrats do him the favor of detonating the next nuclear bomb. Pledging precisely such retribution in a March 16 statement, McConnell previewed the nightmare slate of anti-labor, anti-abortion and anti-immigrant bills Republicans would pass when they regain the majority in the future. There is no reason to doubt McConnell’s ability to deliver these chilling results — if the filibuster disappears.

At the moment, full repeal seems unlikely because some moderate Democrats are not on board. A seemingly more modest proposal has emerged among some in the party to exempt from the filibuster certain “urgent” bills such as those pertaining to voting rights or climate change.

This idea is just as dangerous. Every bill is critical to one constituency or another. The slope is endlessly slippery. The other side has a list of urgent bills as well, and theirs include limiting voting rights and blocking regulation of fossil fuels. Soon, the exceptions will swallow the rule and the filibuster will be gone.

Without the filibuster, the Senate would become revenge-soaked, Hatfield and McCoy-style, as the two sides take turns passing laws over the futile objections of their adversaries. If Democrats expand voting rights, the next Republican majority will constrict voting rights. If Democrats expand the membership of the Supreme Court, Republicans will expand it further to add GOP appointees.

Some, such as Washington Post columnist Paul Waldman, argue that such policy swings are appropriate in a democracy: “It’s what an accountable system is supposed to look like; otherwise, the voters never get what they vote for.” True, in many European countries, the government simply enacts its program. But compromise and moderation are baked into those parliamentary systems, as multiple parties compete for proportional representation and the government falls if it loses support from one wing of the coalition or the other.

The U.S. system is different: a rigid, increasingly polarized two-party, winner-take-all-contraption where power is often decided by a tiny margin. Whoever wins, the Senate filibuster is a cushion against the sudden imposition of that party’s policy wish list on the rest of the country.

Without that cushion, each shift in congressional control will unleash a legislative free-for-all. Half of the country will be euphoric and the other half infuriated. This would be an unhealthy scenario for any democracy, but an especially alarming prospect for ours, where there is already so much distrust of institutions and demonization of opponents, and where the violence of Jan. 6 by a pro-Trump mob may be a harbinger of things to come.

Most fundamentally, it is unhealthy if the process by which a nation’s policy disputes are resolved is up for grabs. Just as baseball teams don’t get to claim four outs when they come to bat, the ground rules of our democracy must be obeyed. Challenges to the umpires of democracy — calls to disregard state-certified election results, or to fire the nonpartisan Senate parliamentarian for her interpretation of Senate rules, or Trump’s unceasing attacks on our nation’s courts — should be condemned.

The rule of law is not a mere slogan. It means that laws and rules apply equally to all and can be changed only by legitimate means.

So, what’s the solution for those who bemoan the current gridlock but want to avoid civil war?

At least give the traditional legislative process a chance to work. It is noteworthy that 10 Republicans were willing to negotiate with President Joe Biden about coronavirus relief. Their initial offer was too low and Biden knew that negotiation was unnecessary since he had the option to pass his bill under filibuster-less reconciliation process. But if 10 GOP senators were willing to visit the Oval Office to talk about compromise on one bill, shouldn’t Democrats at least explore that avenue on other bills before blowing up the chamber?

(Reconciliation, by the way, is like "The Purge" films in which crime becomes legal for a day. Like the Trump record on nominations, reconciliation is another preview of life without the filibuster where both parties “go big” on either tax cuts or social spending. But at least it is somewhat constrained by budget rules.)

The bill most proponents of filibuster abolition insist must pass immediately without minority input is H.R. 1, pertaining to voting rights and related topics. Voting rights has historically enjoyed bipartisan support. The Voting Rights Act of 1965 was a bipartisan bill and has been reauthorized several times with broad bipartisan support, the last time in 2006 with unanimous Senate support.

To be sure, today’s Republican Party is no longer the party of Everett Dirksen, and H.R. 1 will not pass the Senate in its current form. But is incremental progress possible? How can we know before the bill is even marked up in committee?

If compromise proves impossible, Democrats should consider filibuster reform before leaping to filibuster repeal. Biden has expressed support for requiring bill opponents to engage in live debate, like Jimmy Stewart in the classic film “Mr. Smith Goes to Washington.” Ironically, the “talking filibuster” might actually disadvantage the majority party, which typically wants the ability to conduct other business while a cloture petition to end debate is pending.

The more impactful reform would be to require a bill’s opponents to produce 41 votes against cloture instead of requiring proponents to produce 60 votes to move forward. By shifting the burden, this reform would make it harder to deploy the filibuster casually and would smoke out the “lone wolf” filibuster — one or a handful of members registering objections to a bill that a significant majority favors.

Ideally, such a reform would emerge from bipartisan negotiation as contemplated by Senate Rule XXII requiring Senate rules changes to be approved by two-thirds of the body. That’s what happened in early 2013 when then-Majority Leader Harry Reid and GOP leader McConnell negotiated mutually agreeable changes to filibuster rules, before the nuclear option was deployed later that year with respect to nominations.

The crux of the issue for Democrats is this: Does the short-term gain from enacting new legislation outweigh the danger of losing important principles, protections and authorities in current law?

A future Republican majority in the Senate is inevitable, given the natural ebb and flow of American politics and the Republican skew of the Senate itself, where Wyoming has the same representation as California. Nothing Democrats could accomplish by majority vote in the current Congress would be immune from immediate repeal by majority vote the next. We cannot take for granted that the current legal regime — and the crucial regulatory fortress built since the New Deal — would survive the next time Republicans control the Congress and the presidency, which could be as soon as 2025.

I have written elsewhere that I believe the filibuster is valuable in its own right, as a device to encourage bipartisanship and moderation, consistent with other checks and balances in our constitutional system. But one need not admire the filibuster as a positive force to recognize how dangerous its absence would be.

There is a reason a unilateral rules change is known as “the nuclear option.” Unless the doctrine of mutually assured destruction is respected, the Senate blows up.