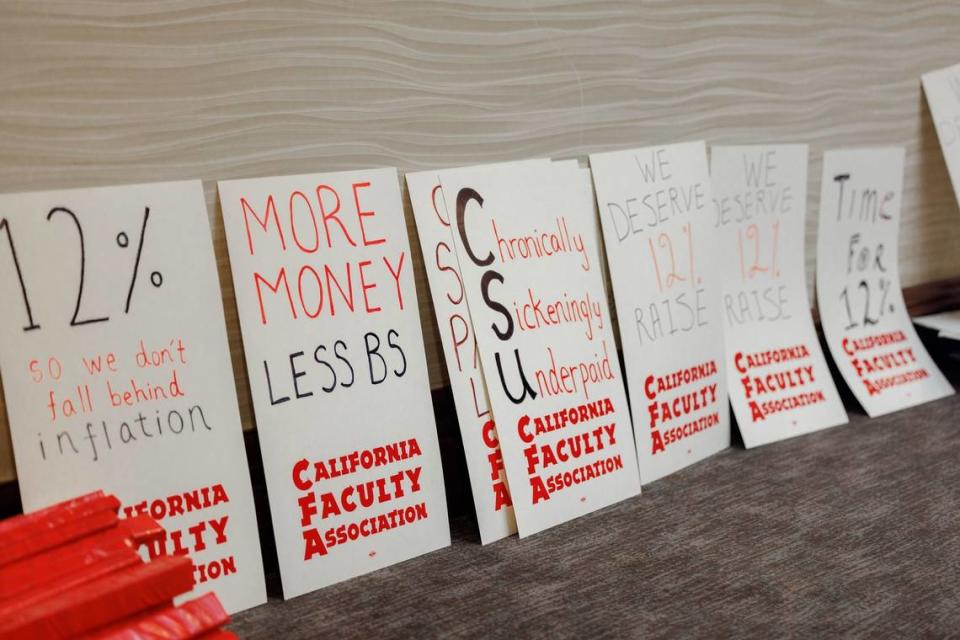

A potential CSU faculty strike for better pay reflects profound job dissatisfaction | Opinion

The California Faculty Association (CFA), representing 29,000 California State University (CSU) faculty, has voted to strike if our bargaining team cannot reach a satisfactory agreement with CSU administrators. I have a ground-level perspective on why faculty are at a breaking point: CSU administrators are completely unresponsive to employees who teach students. Compensation matters, of course, but much of our frustration stems from system failures that matter for students and faculty alike. Our working conditions are students’ learning conditions.

I teach physics at Cal Poly Pomona. It enrolls more than 28,000 students, roughly half of whom study science and engineering fields. Running a physics department is vital for educating scientists and engineers, but it is becoming harder every year. Each semester, the science departments struggle to hire student assistants who help keep labs running. Sometimes the problem is a lack of funds, but more often it is about paperwork delays. Even if we start well in advance, there’s no guarantee that anyone will be on the books as an employee by the start of lab classes.

Opinion

There is no campus-level money shortage. From 2014 to 2022, the university budget grew by 67.6%, while enrollment and inflation grew by 13.4% and 24.4% respectively (note that faculty and staff salaries have not kept pace with inflation). Much of the remaining 30% spending growth stems from a 34% increase in the number of administrators.

We have enough administrators to create red tape, but not enough to perform essential functions, as resources flow away from operational needs and toward pet projects. The CSU can hire a director of brand strategy, a vice president for equity and belonging and a chief diversity officer, it but can’t adequately staff purchasing offices, nor can it fix leaky roofs in science labs and music studios full of expensive, delicate equipment. Often they can’t even issue paychecks in the correct amount.

The CSU is great at hiring administrators — except those needed to lead core academic units. Our Huntley College of Agriculture, long a point of pride, has had interim deans since 2017. The Colleges of Engineering and Education both spent 2020-2023 under interim deans, and the associate vice president for faculty affairs, responsible for behind-the-scenes aspects of faculty hiring and evaluation, has been interim since 2021.

Our provost, the campus president’s second-in-command and chief academic officer, was fired after working here less than a year-and-a-half. Short-term leadership makes careful, long-term planning nearly impossible.

As for faculty, the proportion of instructors in tenured or tenure-track positions shrank 9.3% from 2014 to 2022. Tenured faculty balance teaching, research with students and service on committees that handle key university functions. When tenure-track hiring fails to match enrollment growth, teaching increasingly falls to less secure faculty vulnerable to grade inflation pressure, while behind-the-scenes processes are taken over by administrators, many of whom have never taught.

The result is an unresponsive and unaware system, disconnected from ground-level facts known to people who teach students. That disconnect shows when we can’t hire lab assistants; when reimbursement processes are so onerous that some people emulate our K-12 colleagues and buy supplies out-of-pocket; and when buildings and equipment are in disrepair while the administration grows.

Striking for better pay won’t directly address leaky roofs and delayed paperwork, but it does reflect profound dissatisfaction on the ground — dissatisfaction with administrators who grow their own ranks while neglecting the real work of the university. We are emotionally invested in helping students, but the administration is not financially invested in supporting us or improving the conditions under which students learn. Striking is how we can push back, so we will strike.

Striking was not chosen lightly. Many faculty quietly discuss ways to help students while striking, sneaking onto campus to teach or holding class online so nobody sees us in classrooms. Union leaders understandably urge against surreptitious teaching, which would defeat the purpose of a strike. Still, the ubiquity of such conversations demonstrates our priorities. We want to keep teaching our students because we are committed to their success and passionate about our subjects.

We must send a message to CSU administrators: Steer resources to people who teach students, and deliver conditions under which we can best do that work.

Alex Small is a professor and chair in the Department of Physics and Astronomy at California State Polytechnic University, Pomona.