Poulsbo prosecutor quits, says she was pressured to cover up officer's false statement

The Poulsbo city prosecutor resigned in October when the city’s police officers union took a “no confidence vote” in her after she disclosed that a detective filed a document in court containing false information.

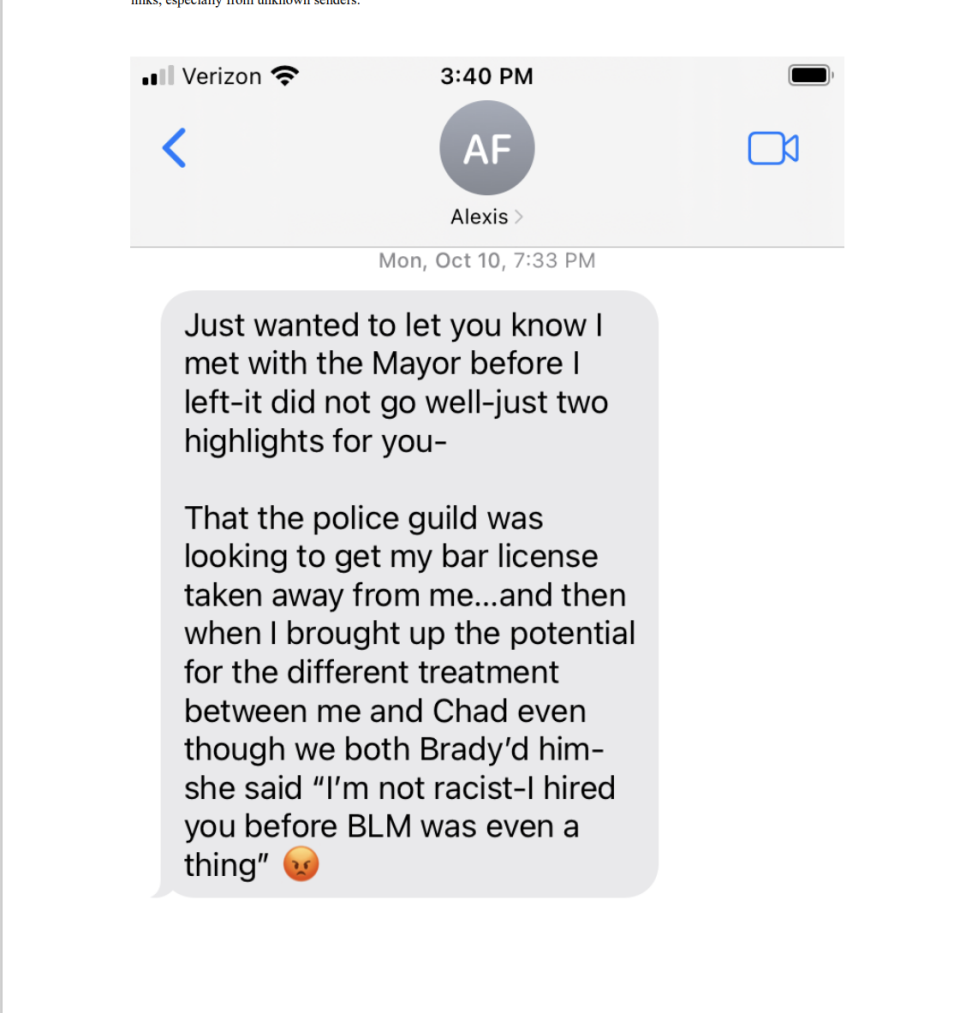

“I was expected to cover it up,” Alexis Foster told the Kitsap Sun in an interview.

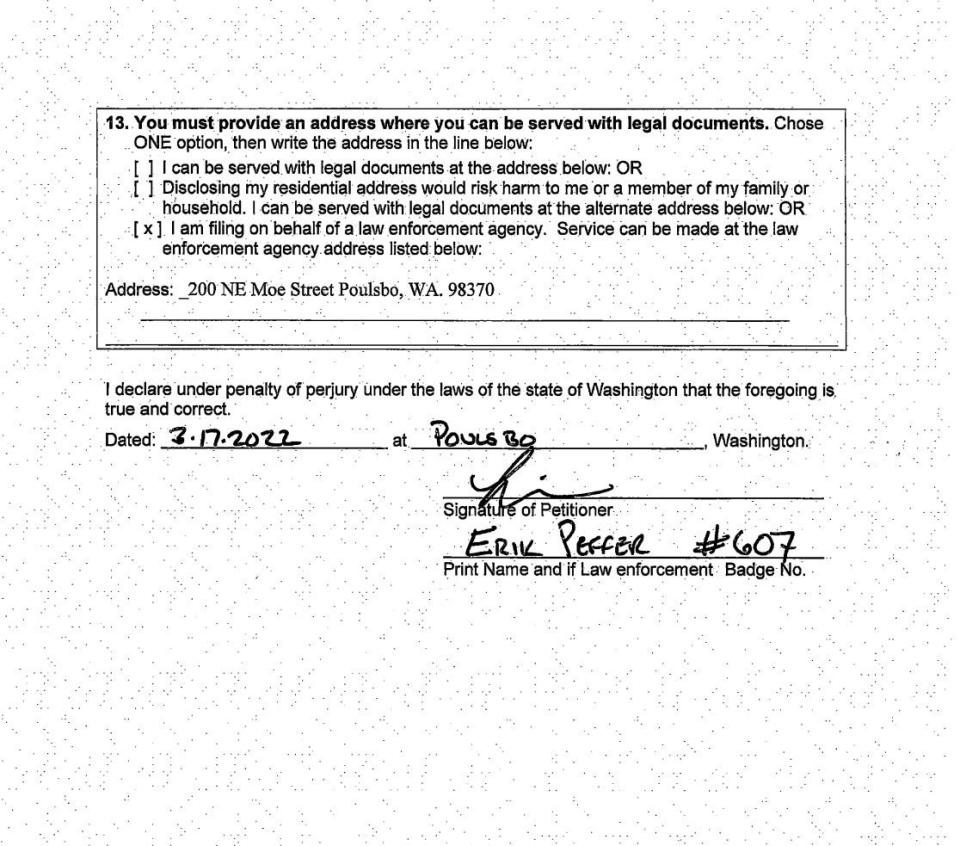

Foster said the pushback from police officers, which was joined by the mayor and police chief, was meant to punish her for taking official notice of flawed documents signed under the penalty of perjury and filed March 17, 2022 in Kitsap County Superior Court by Detective Erik Peffer.

No major negative consequences arose from the filing, or findings of intentional dishonesty. It was not the kind of error that would typically end a police officer’s career. An investigation found it was likely the result of the department’s social worker adding false information to the court form and inattention on Peffer’s part for not catching it.

Despite the relatively low stakes, the blowback against Foster was strong and sustained, resulting in a veteran law enforcement attorney quitting and the city losing its own prosecutor’s office.

Mayor Becky Erickson and police Chief Ron Harding sided with the police union against Foster, with Harding lobbying Foster to not report Peffer. He later sent Erickson a list of additional tasks he wanted Foster to perform, unrelated to the issue with Peffer.

For her part, Erickson wrote in a memo obtained by the Kitsap Sun that she sided with the police because she believed Peffer’s false statement in court was not intentional.

“The conversation I had with Alexis was very heated,” Erickson wrote in notes written in April. “I was reacting to someone casting aspirations (sic) toward another employee without having proof and without even questioning what rationale the officer had for acting the way he did.”

As the dispute dragged on for months, Foster said she believed that Erickson and Harding were building a case to push her out or have her fired.

“I resigned because it was no longer tenable for me to do my job, to do it to the fullest extent of my abilities,” Foster said. “It became a hostile work environment and my hands were being tied in retaliation for following my ethical obligations.”

Foster served as the city’s prosecutor for about six-and-a-half years — prior to that she spent 10 years as a criminal and civil deputy at the county prosecutor’s office. At the time she quit, Foster was the only Black attorney regularly practicing criminal law in Kitsap County courts.

The reaction from police and Erickson suggested a racist motive, with Foster noting that County Prosecutor Chad Enright, who is white, took the same action as she did regarding Peffer.

“And there was no vote of no confidence against him,” Foster said.

When Foster gave notice via email that she was resigning, Erickson responded that she wanted to talk to her: “This email made me deeply sad, but maybe I understand?”

When Foster spoke to her, she said she raised the issue of racism, which angered Erickson, who yelled at her: “I’m not racist. I hired you before BLM (Black Lives Matter) was even a thing.”

Poulsbo had contracted with the county for misdemeanor prosecution services until 2015, when Erickson suggested the city was “overpaying” for the services and the city hired its own prosecutor.

After Foster quit, the city resumed its contract with Enright’s office to prosecute misdemeanors inside the city limits at the cost of $131,500 a year.

Enright backed Foster’s legal analysis, saying Foster did the right thing disclosing Peffer’s false statement.

Like Foster, Enright’s deputies will also be disclosing Peffer’s false statement to defense attorneys in Poulsbo Municipal Court.

“She made the right decision,” Enright told the Kitsap Sun. “I made the same decision.”

Officials asked for questions, didn’t respond

When contacted by email, Peffer requested questions be sent to him. Instead of responding to the questions, his attorney, Alan Harvey, contacted the Kitsap Sun to say Peffer was unable to respond because of department policy.

Harding did the same: requested questions be emailed and then did not respond. Instead, he sent the questions to the city’s Human Resources department and to have attorneys review them. He said Thursday he didn’t know when the city would respond.

Erickson wrote Thursday in an email to a request for an interview that she was in a meeting and said it would be “helpful” if questions were given to her in writing. The Kitsap Sun gave her until 10 a.m. Friday to return a telephone call requesting comment. Erickson did not respond.

Foster did not request questions in advance when contacted, she gave multiple interviews to the Kitsap Sun and responded promptly to requests for comment on documents received by the newspaper.

Brady list

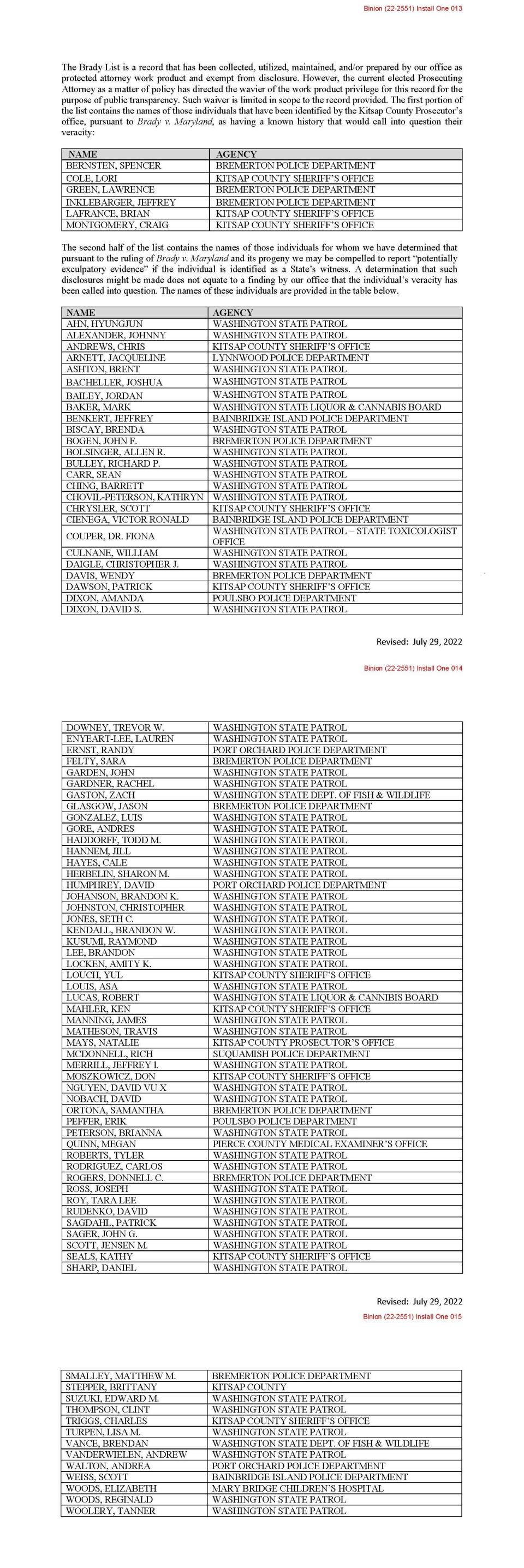

Central to the upheaval is the unsuccessful effort to prevent Peffer’s name from being added to the county’s “Brady list.”

The 1963 U.S. Supreme Court ruling in Brady v. Maryland requires prosecutors to give people charged with crimes all evidence that could be used in their defense, including information that could be used to “impeach” the credibility of the state’s witnesses.

Kitsap County prosecutors maintain a two-tier list of officers or other state’s witnesses, the so-called Brady list. One tier is for those whose acts of dishonesty essentially preclude prosecutors from calling them as witnesses in trial.

The second tier of the list – which has far more names – consists of law enforcement officers and other state witnesses who were not necessarily caught in a lie or found to have committed misconduct, but have something documented in their past that is potentially impeachable.

Prosecutors still call as witnesses those on the second tier of the list and many continue to work in law enforcement.

The list obtained by the Kitsap Sun from the prosecutor’s office in response to a Public Records Act request, updated in July, shows Peffer’s name on the second tier.

Conflict started with a review of records

While reviewing police records in March 2022, Foster noticed that Peffer had signed an extreme risk protection order under the penalty of perjury and submitted it to Kitsap County Superior Court.

The petition for the order, which allows for the seizure of guns from people who pose a significant danger, described a .38 caliber pistol that police wanted to seize and stated it was inside the residence of a suicidal woman. Earlier that month the woman had shot herself in the leg and officers didn’t want her to have access to guns when she returned home from the hospital.

However, another document reviewed by Foster showed that Peffer had personally seized that gun at the time police were called to the woman’s residence.

Foster said that in keeping with a prosecutor’s duty under Brady v. Maryland, she added Peffer’s name to the city’s “Brady list.” Records show she consulted with county prosecutors, who conducted a review and added Peffer’s name to their list.

She also notified Harding, saying an investigation into the reason for the discrepancy was warranted.

Though Harding initially resisted starting an official investigation, one later found the department’s behavioral health navigator Jamie Young, a social worker, had prepared the petition. It was the first time she had done so, and others in the department were similarly unfamiliar with filling out the petitions.

The investigation also found that while Peffer did not intend to mislead the court, the document he signed and filed was inaccurate and it “likely” affected the judge’s decision.

While preparing the order and casting about for assistance, Young wrote an email to Foster, saying: “Hi! I have a question about ERPO when you have a moment.” Foster did not respond.

Peffer told the investigator hired to look into the matter that when he was in court for the first hearing on the petition, he told the judge the gun in question was in possession of police — apparently accurate information but contradicting the information in the document he submitted with his signature.

Foster said her belief was that Peffer had not vetted the petition thoroughly before filing it with the court – rather than intentionally trying to mislead the judge.

However, intent does not matter, she said, when it comes to making demonstrably false statements in court. Foster said the fact that Peffer signed and submitted a document under the penalty of perjury containing information he should have known was false required her to disclose it to defense attorneys under the requirements of Brady.

Harding did not see it that way, and urged Foster to change her mind.

“I do not believe we are anywhere close to a situation that would require you to take any action regarding Brady,” Harding wrote in an April 14, 2022 email to Foster, obtained by the Kitsap Sun, where he told Foster there were “extenuating circumstances” she should consider and he would not investigate further. “I think this is a situation where no one had any intent to be deceptive in order to achieve an outcome based on that deception.”

Making no mention of the underlying issue of Foster noting Peffer’s false statement, records show that in July, Harding sent Erickson a list of “items” and “agreements” needed from the prosecutor.

In those documents, Harding complained that Foster was not responding quickly enough to inquires about seizures and forfeitures and was not providing training to officers in a timely manner.

Harding did not respond to a question from the Kitsap Sun about the timing of his requests.

Foster took this as retaliation, saying Harding was drumming up a list of tasks and grievances about her, with Foster saying she believed the true intent was Harding and Erickson crafting reasons to fire her.

In Erickson’s notes, obtained through the Public Records Act, she admits to threatening to fire Foster when she raised the issue with the mayor.

“I said if she is wrong, and (Peffer) sues us, and we lose it would lead to her termination,” Erickson wrote.

Police union votes ‘no confidence’

In a June letter to Erickson, Sgt. Shawn Ziemann, president of the city’s police union, wrote that an “overwhelming majority” of members of the Poulsbo Police Officers Association voted that they had no confidence in Foster.

Ziemann requested that Erickson provide officers “competent outside counsel on all issues relating to legal advice” that Foster had previously provided. The Kitsap Sun obtained the letter through a state Public Records Act request.

“This is based upon a severe deficit in trust and confidence that the city prosecuting attorney is incapable of aiding the members” of the association, Ziemann wrote.

Officers were upset because Foster had contacted county prosecutors about Peffer’s false statement — leading Peffer to be added to the county’s Brady list — before the internal affairs investigation was completed, Ziemann wrote.

Ziemann also cast blame on Foster for Peffer’s error because she did not respond to Young’s email.

Documents show that in June 2020, Peffer completed a two-hour course from the state Criminal Justice Training Commission on extreme risk protection orders.

Reached by phone Jan. 6, Ziemann told the Kitsap Sun he was en route to a call for service and to phone him back in an hour. Ziemann did not answer and did not respond to messages.

Foster said she would not have been able to offer much help to Young and Peffer, as Peffer had more training than her on the orders.

Further, Foster said: “I would not have thought to advise them to tell the truth.”

Documents provided by the city in response to the Kitsap Sun’s Public Records Act request do not show Foster alleging that Peffer intentionally misled the court.

Rather, in an April 2022 email to Harding, she characterized Peffer’s petition as containing “significant discrepancies that could be viewed as false or misleading statements.”

However, in records written by Erickson and Lt. Howard Leeming, Foster is said to have accused Peffer of being intentionally dishonest.

“Nope, nope,” Foster said, denying she accused Peffer of intentionally dishonesty. “I think this is when they originally started setting me up, in my opinion.”

Chief relented and hired an investigator

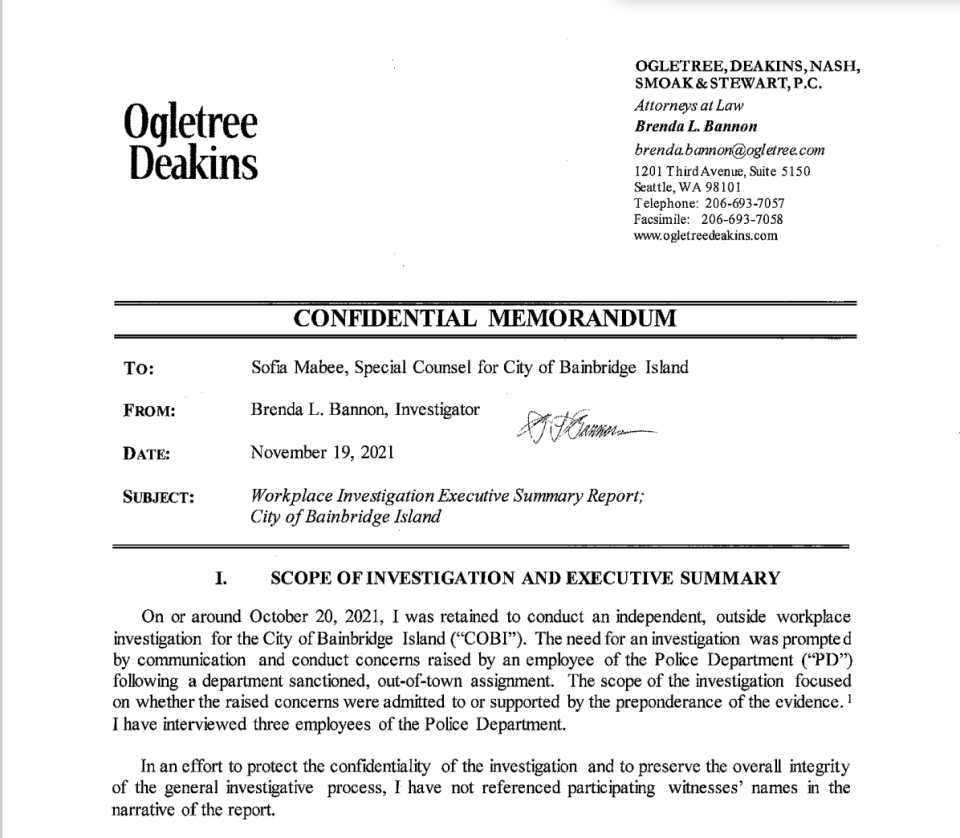

Though he initially said he would not investigate further, Harding hired an attorney to look into Peffer’s false statement, Brenda Bannon, the same investigator who months before had investigated Peffer when he was accused of harassing a female officer at his last agency, Bainbridge Island Police Department.

At the end of her investigation, Bannon found in June 2022 that Peffer had not intentionally misled the court with his false statement, but the petition he filed was “not completely accurate” and that the inaccurate information “likely” affected the judge’s decision granting the order.

Despite the investigator’s findings, Harding opted not to discipline Peffer, though he wrote that Peffer’s false statement is a “perfect example” of what can happen when an officer “casually” approaches their responsibility to ensure information in court documents is accurate.

Same attorney called to investigate Peffer twice

It was the second time in about six months that Bannon, an attorney at Ogletree, Deakins, Nash, Smoak and Stewart, investigated claims against Peffer.

Bannon was hired in 2021 by the Bainbridge Island Police Department, Peffer’s previous workplace, to investigate allegations that Peffer had harassed a female officer while they traveled together to Colorado to extradite a defendant. For that investigation, she interviewed Peffer in November 2021.

Bannon found that “numerous factual disputes exist” between accounts given by Peffer and the female officer, who was not identified in records obtained by the Kitsap Sun.

Transcripts show the female officer made specific allegations against Peffer and he denied them.

On Dec. 9, 2021, Bainbridge Chief Joseph Clark found the allegations against Peffer were “not sustained.” Peffer was hired by Poulsbo police seven days later, Dec. 16, 2021.

Bannon then interviewed Peffer in May 2022 for the false statement he filed in court as a Poulsbo officer.

The harassment allegations followed criticism Peffer received in 2018 as Bainbridge police investigated the shooting death of Donald Duckworth.

Defense attorneys argued that Peffer made errors while applying to judges for search warrants and did not properly log a gun and ammunition seized by detectives from Brian Glaser, who was later convicted of Duckworth’s murder.

Peffer did not respond to questions about the harassment investigation or the criticism he received for his work on the Duckworth case.

Foster said she enjoyed being a prosecutor because she was able to directly have a positive impact on cases and help people.

“I always said I was in two worlds,” Foster said of being Black and a law enforcement official. “I was sort of a bridge between those two worlds. And it’s gone. And that is unfortunate.”

This article originally appeared on Kitsap Sun: Poulsbo prosecutor pressured to cover up officer's false statement