Some praise ruling criticizing NJ school segregation. But what happens now?

A much-anticipated court ruling that was issued Friday said New Jersey had failed to correct the problem of continuing racial segregation in its public schools, exacerbated by the practice of having children attend schools based on where they live. But the ruling's implications for how the state will oversee public schools going forward is far from clear — even as some groups welcomed the ruling and others sounded voices of alarm.

In his ruling in the 2018 lawsuit brought against the state Department of Education, its acting commissioner, Angelica Allen-McMillan, and the State Board of Education by the Latino Action Network, the NAACP and other organizations, Superior Court Judge Robert Lougy agreed with part of the plaintiffs’ complaint: that school segregation exists and it is the state’s constitutional duty to fix it.

But final judgments did not strongly favor either party.

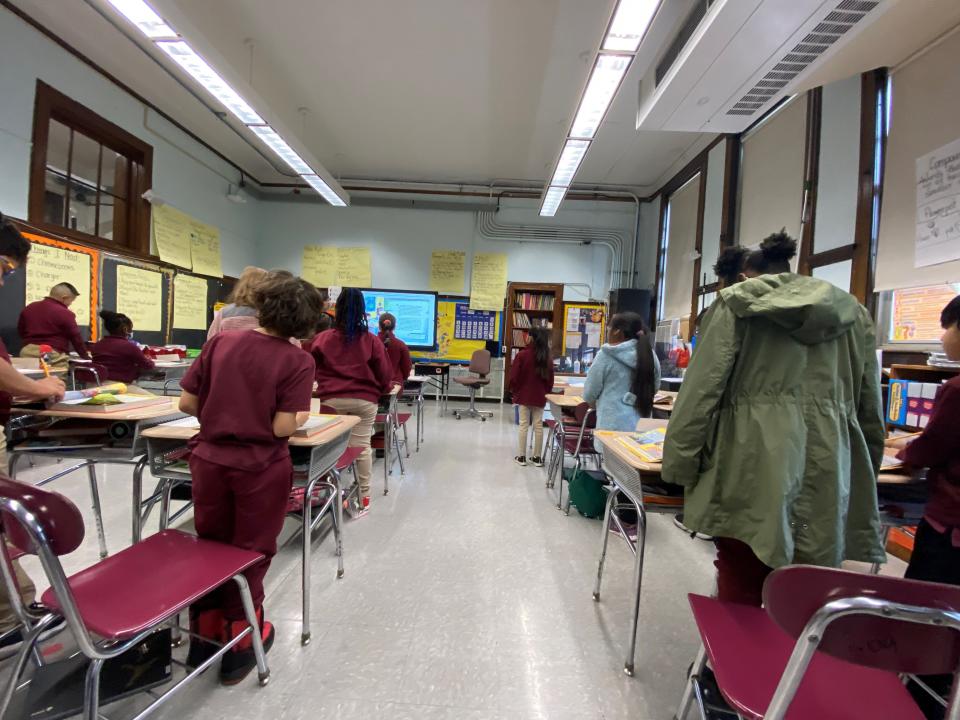

Story continues below photo gallery.

At the core of the lawsuit was New Jersey’s residency law, which assigns students to schools based on their ZIP codes. The court agreed that this contributed to segregation but said the state could find workarounds to integrate schools within that framework. It did not issue an order to block or change how students are assigned to districts or individual schools based on where they live.

The next step is for the case to go to trial or for the two sides to begin settlement discussions.

Judge rejected argument that segregation is inevitable

Lougy rejected the state’s position that the case was irrelevant and segregation is inevitable. The state had argued that the number of white students continues to decline statewide, making it difficult to balance demographics.

Lougy sided with the plaintiffs, saying the state had “intentionally failed” in its constitutional duty to provide equal protection to students by letting them continue to attend segregated schools.

Research shows that New Jersey is among the five states with the most segregation in schools, said Robert Kim, executive director of Newark’s Education Law Center, which advocates for funding equity and represents some of the state’s poorest districts.

Even without a clear winner in the case, the court signaled that the problem of segregation exists, he said. The group welcomed the ruling but said the court could have gone further and required the state to come up with a remedy.

“Friday's ruling slams the state of New Jersey's inaction in the face of rampant segregation in its schools,” said Stefan Lallinger of Bridges Collaborative, an integration-focused group at the Century Foundation, a progressive think tank in Washington, D.C.

State must consider remedies

Even without a broader judgment, the state has to think about how it will address segregation as the case moves into its next phase, Lallinger said. “Regardless of where the litigation goes from here, it is clear that the state of New Jersey will need to immediately begin considering what remedies it will provide,” he said.

The ruling noted that the state constitution “clearly and explicitly forbids segregation in public schools, no matter the cause,” Lallinger said. He called on the state to take measures to address it. “Now more than ever, the Murphy administration must … adopt a new posture toward segregation, rather than its prior defense that it was blameless and helpless to do anything about it,” he said.

The ruling was not as far-reaching as some advocates might argue, said Neal McCluskey, director of the Center for Educational Freedom at the libertarian Cato Institute in Washington, which looks at educational solutions that involve less intervention from the government.

Even though the court agreed that segregation in schools is real, the judge’s decision was “unenthusiastic” about either side's case, he said, by granting fewer claims for the plaintiffs than the state.

The ruling also clearly says the state has not violated a student’s right to be educated by implementing its own residency laws. That “suggests home rule is a sufficient defense against state-level segregation charges,” McCluskey said. He was referring to New Jersey’s prideful tradition of granting local control to its boards of education, as long as they comply with state laws.

The state has 674 schools districts that vary in size, demographics and income, with very wealthy, tiny districts just a stone’s throw away from large, low-income ones.

Offering parents choices

Efforts to balance schools by race are likely to succeed when parents and families are offered choices, McCluskey said, unlike older integration efforts that relied on busing children between districts.

People tend to gravitate naturally toward groups that are similar to them, so integration works better when there are incentives, such as magnet schools with educational themes, or in controlled choice systems where parents can rank schools according to their preference, he said.

More: NJ has failed to address 'persistent racial imbalance' in schools, judge rules

More: Will New Jersey desegregate its schools? Ruling in 2018 lawsuit expected

Lallinger, of the Century Foundation, also suggested some form of choice to drive integration efforts. Regional or cross-district magnet schools, merging districts in segregated and contiguous municipalities, and stricter oversight of within-district zoning to prevent segregation were options the state can begin to consider, he said.

Micah Rasmussen, director of the Rebovich Institute for New Jersey Politics at Rider University, said he was bused to an inner-city middle school as a student in South Jersey through a program that ran in the 1970s and '80s.

“When I graduated from Vineland High and began college, many of my classmates had never been to school with students who didn't share their skin color,” he said. “So I'm a big believer that everyone misses out in a school system that keeps apart students of different views, perspective and backgrounds.”

People tend to get over their discomfort with change pretty quickly, Rasmussen said, “and begin to see the value there.”

But politicians are likely to be “gun-shy” about implementing a “statewide mandated fix,” he said, meaning the odds are that little will happen by way of big changes and that the process will take a long time.

Fear of losing home rule

The Murphy administration has not issued a statement on Lougy's ruling other than the Office of the Attorney General saying it is reviewing it. But state Sen. Jon Bramnick, R-Union, tapped into fears around the residency question.

The decision may “take away” New Jerseyans’ right to send their children to neighborhood schools when the case goes to trial, Bramnick said in a statement.

Lougy, however, commented on the residency issue in the ruling, saying the state could not be accused of violating the law by following another one and “complying with the residency statute.”

Neither side made a compelling case that it was clearly right, including the plaintiffs, who established segregation but could not prove it was statewide, said McCluskey, of the Center for Educational Freedom.

"Given the geographic interplay and the wide range of district sizes, configurations, and racial composition, plaintiffs’ broad, generalized non-geographic data set fails to establish that, if public school children were able to go to another district, and doing so was feasible and practicable, they would receive a diverse education. In some districts, that may be the case; in others, it may not be," the ruling said.

Bramnick is pushing a constitutional amendment that prohibits “any student from being compelled to attend public school other than one nearest to student's residence.” The bill, introduced in 2022, is sponsored by three fellow Republicans.

The state has to provide equal and equitable protection to its students, said Kim, of the Education Law Center. "It has a duty to figure out what that means and implement those laws. It's not helpful when there are individual pronouncements that individual districts or areas will not do certain things.

"I think we have to wait and see how this progresses," Kim said. "It's very clear that it would be desirable for remedies to be voluntary … but it's not helpful to put up walls when we are trying to make schools more diverse.”

This article originally appeared on NorthJersey.com: Some praise ruling criticizing NJ school segregation. What's next?