Preservation of Neosho school attended by George Washington Carver gets national grant

- Oops!Something went wrong.Please try again later.

For decades, historians have worked to preserve and restore the Neosho school where the prominent Missouri-born scientist George Washington Carver and hundreds of other Black children were educated.

The project, largely reliant on donations, received a boost Tuesday with a $70,000 grant from the African American Cultural Heritage Action Fund, a program of the National Trust for Historic Preservation.

The 1872 Neosho Colored School, listed on the National Register of Historic Places, was one of 30 projects selected this year from among 660 proposals. It was the only recipient in Missouri.

Lawana Hollard Moore, a historic preservation expert and storyteller with the national fund, said there is an urgent need to "protect, preserve and interpret these valuable American assets."

The two-room, 380-square-foot wooden structure on Young Street opened in 1872, just seven years after the end of the Civil War, and remained in use until 1891. It is a rare surviving example of a Reconstruction-era African-American school.

"What makes it special is that it was the first school attended by Black agricultural scientist and inventor George Washington Carver," Holland Moore told the News-Leader.

"It was important to us because for far too long sites of African-American history such as this have been overlooked and undervalued and we believe that African-American historic sites deserve to be thoughtfully stewarded and invested in and cared for at the same level of Thomas Jefferson's Monticello."

By elevating the school and other historically significant sites, Holland Moore said lessons of the past live on.

"Our grants provide the support and the capital that is necessary to ensure that these African-American sites are preserved and recognized and the story behind is told to a broader audience," she said.

"This makes such a transformational difference for so many of these sites."

Since 2017, the national fund 5,638 proposals requesting $655 million. Since 2018, the Action Fund has supported 242 grantee projects through its investment of $20 million.

Past grant recipients from Missouri include the Satchel Paige House and the Sarah Rector Mansion in Kansas City and The Ville, a historic African-American neighborhood, in St. Louis.

Brent Leggs, executive director, African American Cultural Heritage Action Fund, said: “The history embodied in these places are emblematic of generational aspirations for freedom, the pursuit of education, a need for beauty and architecture, and joys of social life and community bonds."

'Next step is rehabilitation of the interior'

Carver was born in Diamond — home of the 240-acre George Washington Carver National Monument, established in 1943 — but he was not allowed to enroll in school there.

To pursue an education, he moved to Neosho and into the home of Andrew and Mariah Watkins in 1876. Neosho, at the time, had a Black population of 130.

Carver is a noted inventor, scientist, humanitarian and educator who taught for 47 years at the Tuskegee Institute in Alabama.

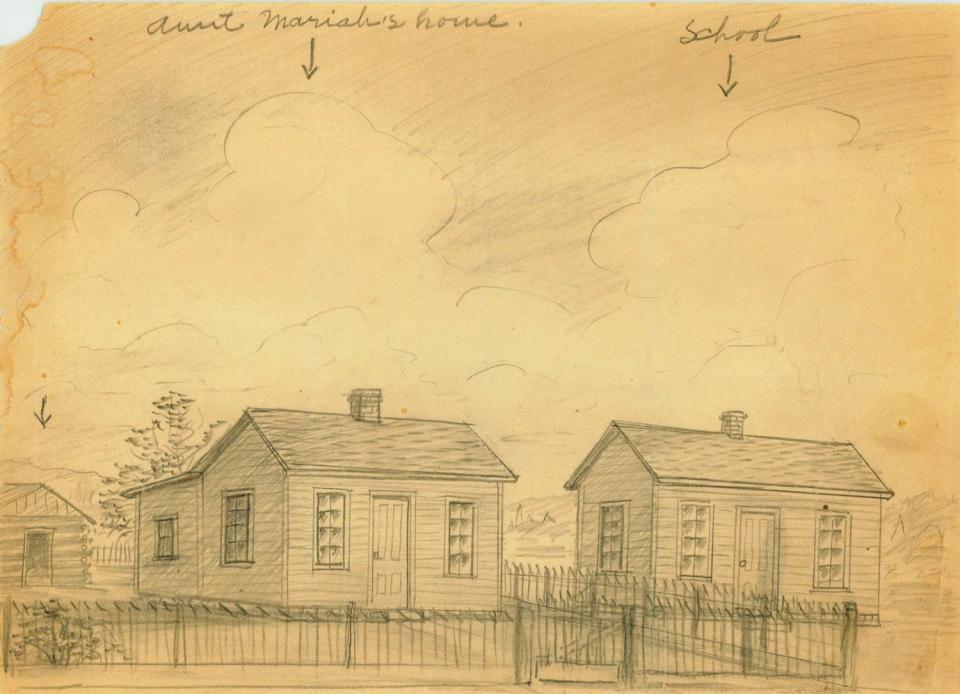

He captured his memory of the school and the nearby home in drawings, depicting the school's gable roof and small interior chimney.

Often referred to as the Carver School House, the structure became a private home in the 1890s and remained that way for a century.

The wooden structure became fragile and was slated for demolitions when historians led a fight to save the school.

Over the decades, the building had been renovated and added onto but many of the original materials remained intact. The horizonal board wainscoting, plastered walls and ceilings, window framing and early or original flooring were uncovered.

Lana Henry, president of the Carver Birthplace Association, said it took decades to get the structure added to the National Register.

Other work included removing non-historic add-ons to the building, stabilizing the structure and rehabilitating the exterior.

"The next step is rehabilitation of the interior of the schoolhouse," Henry said. "While it was been a long process, the support just keeps showing up as we continue to pursue the finish line."

More: Celebrate Black history during Springfield's first city-wide Juneteenth weekend festival

In applying for the grant, the association said outlined what it hoped to accomplish from March to September of 2024, including:

Repairing historic lath and plaster ceilings, interior trim and wainscoting;

Repairing and refinishing the historic wood floor;

Replicating the bracketed wood board chimney cabinet;

Upgrading the electric system;

Adding a security system, interior and exterior lighting and HVAC;

Installing an antique pot belly stove and stovepipe;

Constructing an ADA-compliant ramp and concrete walkway to the east door.

In the project description, the association said every effort will be made to preserve the original features but where those are missing, replicas will be used or sections will be rebuilt to reflect historic features.

The grant application described the school as "a valued tangible historic resource directly connected" with Carver's life.

To interpret the significance of the site, the association and the National Park Service completed a 180-page study called "Thirst for Knowledge: Historic Context for the 1872 Neosho Colored School" that included data about slavery in Missouri, the impact of major civil rights laws and related historical accounts.

One example from 1894 showed the racial volatility of the times. A Neosho man named Hewlett Hayden — who likely attended the school a few years before Carver — was arrested for allegedly shooting a man near Monett. On the way to jail, a lynch mob overpowered the men guarding Hayden and hung the man from a telephone pole near the tracks.

A newspaper account noted "50 to 100 in the lynching party and none were disguised," indicating little fear of reprisal for such violence.

The study also described the impact Andrew and Mariah Watkins had on Carver. In exchange for a place to stay, Carver helped Aunt Mariah, a former slave, with chores. She reportedly taught him about herbal medicine and domestic skills.

Future plans for the Carver school

A planning workshop conducted by the Carver Birthplace Association and the national park identified priorities beyond restoring and preserving the 1872 Neosho Colored School. They include:

Using the school as an educational satellite to the George Washington Carver National Monument, integrated into the programming;

Acquiring adjacent properties to develop a museum;

Working with a consortium of higher education institutions, which support the project with fundraising;

Raising funds for an independent restroom, separate from the school.

Claudette Riley covers education for the News-Leader. Email tips and story ideas to criley@news-leader.com.

This article originally appeared on Springfield News-Leader: Grant aids preservation of Neosho school of George Washington Carver