How President William McKinley and his native Ohioans responded to war with Spain

- Oops!Something went wrong.Please try again later.

On February 15, 1898, — 125 years ago — the armored cruiser USS Maine was destroyed in an immense explosion in the harbor of Havana, Cuba. Approximately 355 American sailors and marines died. Of 94 survivors, only 16 were unhurt. It was the worst loss of military lives since the battle on the Little Big Horn River in 1876 shattered George Armstrong Custer’s Seventh Cavalry.

The USS Maine had been sent to Havana to protect American lives and economic interests. Its loss propelled a reluctant President William McKinley of Ohio toward a war he did not want, but was persuaded to undertake.

The relationship between the United States and Cuba was a long and deeply involved one. Conquered by Spain, Cuba had been a Spanish colony for more than four hundred years.

Even as Spain had declined as a colonial power because of Napoleonic occupation, the loss of colonies to revolution and internal conflicts at home, Spain had held onto Cuba as an integral part of its national identity.

It was an identity increasingly challenged by the United States, located just 90 miles from its shores.

Over the years after the American Civil War, American investors had become increasingly the purchasers of Cuba’s main export – sugar. By 1898, America was receiving 90% of Cuba’s exports and sending the country 40% of its imports. Cuba may have belonged to Spain politically, but economically it belonged to the United States.

It was to protect those investments that the Maine had been sent to Havana.

There had been many revolts by the Cuban people against Spanish rule over the years. In general, they had been brutally suppressed by the Spanish government. But in 1895, Cuban revolutionary Jose Marti had launched a three-pronged liberating invasion of the island. Initially successful, the assault soon became bogged down in a long guerrilla struggle. Spain responded with the activities of General Valeriano “The Butcher” Weyler, who hadno problem placing whole villages he did not like in “reconcentration camps.”

All of this was carefully followed and reported by the new, inexpensive “yellow journalism” of Joseph Pulitzer at the The New York World and by William Randolph Hearst at The New York Journal. Both papers and many more across the country attacked the Spanish in editorials and called for the U.S. to go to war.

In 1898, Assistant Secretary of the Navy Theodore Roosevelt saw conflict coming and called for America’s newly built steel warships of the Atlantic and Pacific Squadrons to prepare for war. Strikingly superior to Spanish warships, they did just that.

President McKinley and House Speaker Tom Reed, a Republican from Maine, did not want a war. Both felt, along with most American business leaders, that a peaceful solution to Cuba’s problems could be found. But the explosion of the Maine, blamed by yellow journalism on intentional Spanish activity but now believed to be the result of a loose unattached Spanish mine, pushed McKinley and his cabinet into action. On April 14, 1898, he went to Congress and asked for action against Spain in Cuba as the battle slogan "Remember the Maine! To hell with Spain!" echoed across the nation. Spain responded with a Declaration of War and the U.S. reciprocated.

At the outbreak of the Spanish American War, the United States' armies consisted of about 25,000 men. McKinley called for a volunteer army of militias and federalized national guards of 50,000 men. The United States was a country that had not seen a major conflict since the Civil War, and a lot of young men wanted a war of their own. In the end, more than 200,000 young men volunteered.

A significant number of them came from Ohio and were mobilized in a camp on the east side of Columbus.

Ohio Governor Asa Bushnell was a Civil War veteran, as was his Attorney General Henry Axline. They and their subordinates immediately took control of a 500-acre tract east of Alum Creek called Bullitt Park and worked with the City of Columbus to bring water lines and electric power to the area. An army camp was laid out and was called Camp Bushnell.

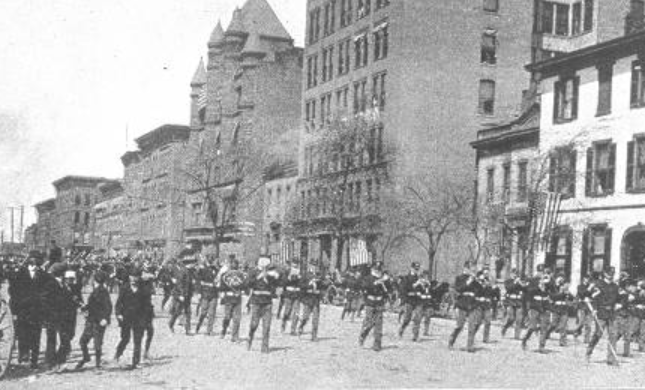

For a period of several weeks in the spring of 1898, it became the home of more than 8,000 members of Ohio’s militias and its National Guard. In May 1898, the 14th Ohio National Guard became the Fourth Ohio Volunteer Infantry and marched proudly to trains that took them to Chickamauga, Tennessee, and eventually by boat to Puerto Rico. Other men from Columbus were sent to Cuba, where they fought with Teddy Roosevelt’s Rough Riders and others went to the Philippines.

While some men died fighting, more men died from disease – yellow fever, malaria and cholera. The war was over in less than 90 days. The U.S. by treaty received control of the Philippines. Puerto Rico, Guam and other islands. The United States in less than a few months had become a colonial power.

Ohio’s soldiers came home to parades and welcomes. The soldiers and sailors formed their own organization called the United Spanish War Veterans, and with a little legislative help placed a statue of one of their own by the front door of the Statehouse in Columbus. He is still there today.

Local historian and author Ed Lentz writes this " As It Were" column for The Columbus Dispatch.

This article originally appeared on The Columbus Dispatch: The sinking of the USS Maine 125 years ago led to short war with Spain