Presidential emergency powers can upset constitutional balance | Opinion

Contemporary utilization of emergency powers by American presidents is not consistent with the definition of an emergency — defined as the need for immediate action to confront unforeseen circumstances potentially or actually injurious to the nation — or with the traditional juxtaposition of constitutional authority between Congress and the president in that area.

The imbalance is as much a consequence of presidential aggrandizement as it is legislative acquiescence.

To the extent that emergency powers were contemplated by the Constitution's framers, it pertained to Congress's granted powers, not to those of the newly created executive. Throughout the first century and a quarter of constitutional history, presidential designation of an emergency mostly ensued after Congress had acted first.

However, starting with President Woodrow Wilson, chief executives have employed tools to declare emergencies on their own without initial legislative approval, often relying on previous laws from a different era. The excesses of the Richard Nixon administration in this area and others led Congress to pass the National Emergencies Act of 1976, which requires presidents to request renewal of emergency declarations annually and furnishes a process for congressional cancellation of them.

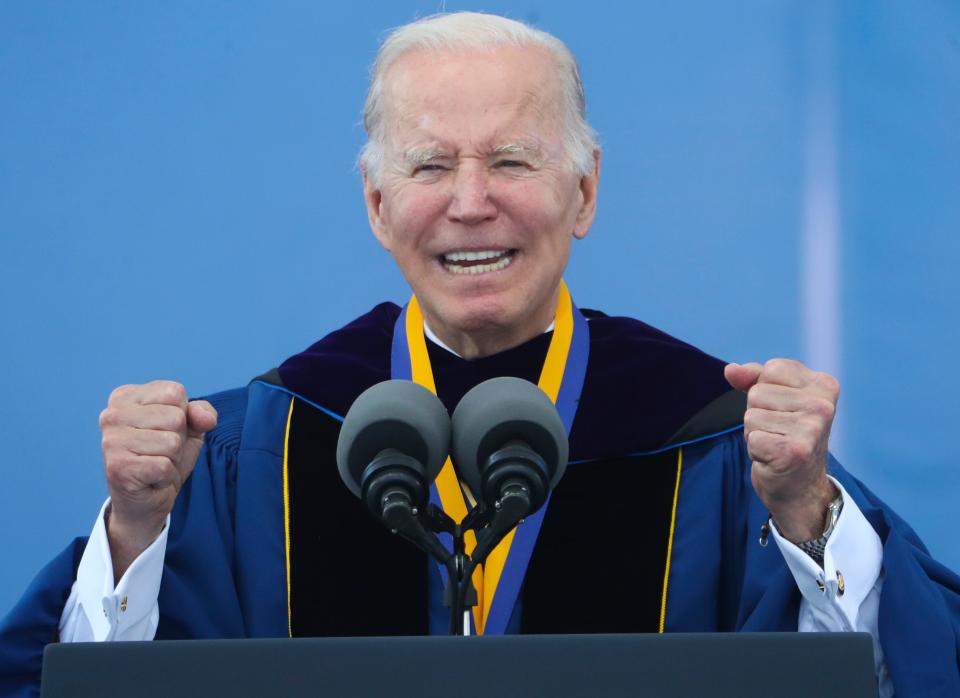

Since the latter act was enacted, every chief executive from Jimmy Carter to Joe Biden has utilized independent emergency declarations, mostly by executive order. The categories of such actions have included economic, military, trade, sanctions, arms, maritime, legal, and public health areas. The problem is that of the 72 emergency declarations issued since 1979, 42 of them are still in effect; only the 11 total emergencies declared by Presidents Ronald Reagan and George Bush have officially legally ended.

Nowadays, presidents increasingly assert extra-constitutional mechanisms to justify actions. When that is combined with a congressional majority of the president's party, there is little that can be done to stem such abuse. However, when a president confronts an opposition-controlled Congress, the result is often a tit-for-tat effort by both branches to augment weapons against each other. Another outcome has been the intervention of the courts. For example, the Supreme Court has already rejected Biden's attempts to invoke emergency powers to justify an eviction moratorium and vaccine mandates.

To the extent that emergency alerts are necessary, they should be transmitted only in an authentic crisis. Further they should serve a limited role at the time enacted. Additionally, they should not be used to address long-term dilemmas. Most importantly, the employment of emergency powers should be a shared function between Congress and the president, in that order. Without that framework, there is neither legitimate authorization nor accountability.

Samuel B. Hoff is George Washington distinguished professor emeritus of history and political science at Delaware State University.

This article originally appeared on Delaware News Journal: Presidential emergency powers can upset constitutional balance