When presidents get primaried

- Oops!Something went wrong.Please try again later.

- Oops!Something went wrong.Please try again later.

- Oops!Something went wrong.Please try again later.

- Oops!Something went wrong.Please try again later.

- Oops!Something went wrong.Please try again later.

There are two years to go before the next presidential election and already there's an effort underway to replace Joe Biden at the head of the Democrats' ticket. RootsAction, a progressive group, announced this week it will run an ad campaign aimed at blocking his renomination. "Our immediate goal within the Democratic Party is to 'dump Biden,' much as the anti-Vietnam-War forces among Democrats set out to 'dump [Lyndon] Johnson' in 1967, which led antiwar candidates Eugene McCarthy and Robert Kennedy to enter the race," the group says on its website.

It's true that Johnson withdrew from the 1968 race in the face of massive intra-party opposition, famously declaring: "I shall not seek, and I will not accept, the nomination of my party for another term as your president." But the eventual winner of the White House in that election was neither McCarthy nor Kennedy, who was assassinated after the California primary: It was Richard Nixon, the Republican nominee. Sitting presidents don't face primary opponents very often, but it does happen. How has it worked out in the modern era? Here's everything you need to know.

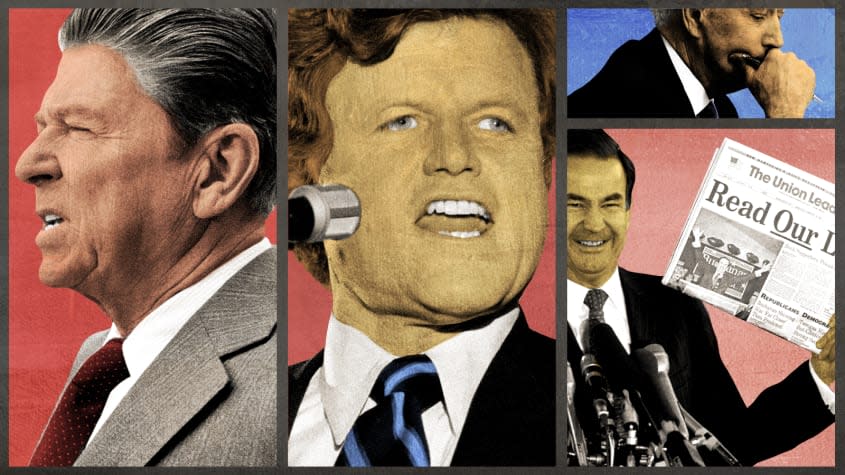

1976: Ronald Reagan challenges Gerald Ford

Gerald Ford was an extremely unusual incumbent coming into the 1976 presidential race — he hadn't been on the GOP ticket four years earlier when Nixon won re-election. But he replaced Vice President Spiro Agnew in office in 1973 after Agnew pleaded guilty to tax evasion and money laundering charges, then ascended to the top spot the next year when Nixon resigned over the Watergate scandal. He was an accidental president, for whom nobody had voted.

Enter Ronald Reagan. The longtime Hollywood actor had become a conservative superstar and made the switch to politics, serving as governor of California from 1967 to 1975. He saw the opening to challenge Ford, and the contest was extremely close: The two men entered the Republican National Convention in Kansas City in a dead heat — Ford held a slight lead, but was short of a majority of the delegates needed to secure the nomination. The result: The last (so far) contested convention by a major political party.

"Contested" might be an understatement: The convention featured brazen, even bare-knuckled politicking by the two camps: "The RNC awarded Ford delegates hotels close to the arena; Reagan delegates were assigned motels as far as 70 miles away, across the state line in Kansas," Craig Shirley wrote for The Washington Post in 2016. At one point, Vice President Nelson Rockefeller "ripped a Reagan sign out of the hands of a North Carolina delegate" and in retaliation "a Utah delegate tore New York's phone out of its base." In the end, Ford managed to eke out a few extra delegates and won the nomination. To no avail: He narrowly lost to Jimmy Carter that fall.

1980: Teddy Kennedy challenges Jimmy Carter

Carter came into the 1980 election season with challenges on every front: American hostages in Iran, high unemployment and rampant inflation at home, and a sense that the country was in crisis. Sensing vulnerability, Sen. Edward Kennedy (D-Mass.) — the younger brother of President John Kennedy and Senator Robert Kennedy, both felled by assassins — made a move to extend the family dynasty: He challenged Carter. One early poll even showed him beating Carter among Democrats by a two-to-one ratio.

And then Kennedy stumbled. Asked during a TV interview why he wanted to be president, the senator stammered, seemingly caught off-guard by the simplest of questions. "Well, I'm — were I to — to make the, the announcement and to run, the reasons that I would run is because I have a great belief in this country," he stammered. His campaign — already struggling under the legacy of the 1969 Chappaquiddick scandal — never quite recovered: Four days after the interview, Carter won a straw poll among Iowa Democrats with 70 percent of the vote.

But that wasn't the end of the story. At that summer's Democratic National Convention, Kennedy was called to the stage with Carter — and conspicuously avoided shaking hands with the president. "Carter is chasing Kennedy around the stage," journalist Jon Ward later said, describing the scene to NPR. "This is after he's just accepted the nomination. It's the pinnacle of his success in the primary. He's won. But after this humiliation on national television, he's kind of lost. It's just bizarre." That fall, Carter lost to Reagan.

1992: Patrick Buchanan challenges George H.W. Bush

The first President Bush was briefly on top of the world: Around the time American forces chased Saddam Hussein's Iraqi army out of Kuwait during the 1991 Gulf War, his approval rating stood at an astonishing 89 percent. But things quickly went downhill after that. One reason: During his 1988 run for president, Bush had memorably vowed never to raise taxes. Two years later, facing a growing budget deficit, he signed a bill that "cut $500 billion from the deficit in five years, in part by raising 'luxury taxes' on items including yachts and pricey cars, among other tax hikes," according to Reuters' Elizabeth Barber. Anti-tax Republicans were furious.

Patrick Buchanan, a "paleoconservative" activist who had worked as an advisor to Presidents Nixon and Reagan, ran against Bush in the 1992 primaries. Bush won handily — capturing nearly three-quarters of GOP voters — but invited his challenger to speak at the Republican National Convention. Buchanan went before a nationwide audience and delivered a startling jeremiad. "There is a religious war going on in this country," Buchanan told Americans. "It is a cultural war, as critical to the kind of nation we shall be as was the Cold War itself, for this war is for the soul of America." The speech is remembered as a pivotal moment in American politics, one that set the stage for Donald Trump's later campaigns. And Bush? He lost to Bill Clinton that fall.

The final scorecard: Over the last 60 years, intraparty challenges to sitting presidents have succeeded mostly in damaging those presidents. But they haven't led to short-term electoral success for the challengers: Their party lost the White House each time.

You may also like

Amazon's epically expensive Lord of the Rings show gets a stunning new trailer

The newly-resurfaced debate on Biden's age and mental fitness

Ukraine strikes behind Russian lines with long-range launchers from the West