'The World’s Greatest Magician' had Ohio roots and rivaled Houdini

- Oops!Something went wrong.Please try again later.

- Oops!Something went wrong.Please try again later.

- Oops!Something went wrong.Please try again later.

Howard Thurston, the last great stage illusionist, was hailed as “The World’s Greatest Magician” in the early 20th century.

But he has been all but forgotten.

He was a contemporary and rival of Harry Houdini, who was more of an escape artist. It was Thurston who provided the spectacle and showmanship – along with levitating assistants, rabbits pulled out of hats and card tricks – that we have come to associate with magic.

“When you think of the spectacular stage show with animals, costumes, assistants and humongous illusions on these big stages, most people don’t realize they’re imagining Thurston’s show,” said Rory Feldman, who has collected more than 65,000 Thurston artifacts, including posters, props, costumes and illusion cabinets.

Thurston visited Cincinnati annually for 26 years, from 1907 to 1932, for a one-week engagement, most often at the Grand Opera House on Vine Street. The city also played a part in the beginning of his career.

Ohio native Thurston enchanted by magic show

Thurston was born July 20, 1869, in Columbus. His father was a carriage maker and failed inventor who suffered financial difficulties. At age 12, Thurston worked as a newsboy, hawking papers on the railway line between Columbus and Pittsburgh.

In his autobiography (serialized in the Cincinnati Post in 1931), Thurston wrote that he became fascinated by horseracing, so he ran away from home to Cincinnati to become a jockey. But when the races closed at the end of the week, he had no money. He sold his penknife for 10 cents.

“That money paid for a stock of afternoon papers, and I began my career as a newsboy on the corner of Fifth and Vine streets, the busiest corner in Cincinnati,” he wrote.

Around this time, he saw his first magic show performed by Alexander Herrmann, the top magician of his day, and received a gold button that he treasured. “Herrmann the Great was my enchanter,” Thurston wrote.

As a showman, Thurston could spin a good yarn and sometimes the details got twisted.

“Today the record of this event has been muddied by Thurston’s many official accounts, interviews, and adjustments to the legend,” biographer Jim Steinmeyer wrote. “It may have been at the old City Hall Theater in Columbus, or at an unnamed theater in Cincinnati, where the newsboys were working.”

Thurston and his newsboy partner Reddy Cadger hopped trains to travel the Midwest until one day Cadger fell off and died. Thurston went on practicing sleight of hand he learned from a magic book Cadger had given him, doing card tricks and sometimes picking pockets.

He was saved from a life of petty crime by prison reformer William M.F. Round. But when he was headed to study for the ministry, Thurston saw Herrmann perform again in Albany, New York, and decided to dedicate his life to the craft of illusion.

‘The World’s Greatest Magician’

In 1897, Thurston introduced his own version of the Rising Card trick at a saloon in Montana. A member of the audience called out a card, and the named card rose off the deck and levitated about a foot to Thurston’s hand above the deck. “Up, up, up!” he’d say theatrically. (Spoiler: The card was clipped to a thin black thread like an invisible clothesline.) The trick made Thurston famous as the “King of Cards.”

He headlined at the Palace Theatre in London for months in 1900, and did private performances for King Edward VII and the Shah of Persia. In 1905, he toured the world, performing for the crowned heads of Europe and Asia.

He graduated from card tricks to perfecting grand illusions when he succeeded Harry Kellar, the “Dean of American Magicians,” in 1907. The two toured together for a year as Kellar retired and passed the magic wand to Thurston as the era’s greatest prestidigitator.

Like many performers, Thurston borrowed or purchased his illusions from other magicians but then made them famous around the world. Sawing a woman in half, the levitating woman, making an elephant or a Willys-Overland automobile vanish. His real skill was his showmanship.

“It was the first stage show to make extensive use of electricity,” his assistant and first wife, Grace, said. “Electric motors turned on many of the illusions, and sparkling filaments and fountains were part of several tricks.”

At his peak, Thurston traveled with 30 assistants and eight train cars full of props, costumes, animals and machinery.

Enquirer drama editor Herman J. Bernfeld wrote about Thurston’s act before his appearance at the Albee Theater in 1932:

“The magician effectively takes his audience out of the land of reality into the realm of illusion, where impossible things occur.

“Cards appear from nowhere at his behest and return to that same limbo. He does the same with women, as well as countless objects. He makes one of his followers rise from the ground, suspended in midair without any apparent means of support. He causes a woman to disappear into a cannon-like contrivance, sets the gun off, and presto! she slides down a rope from a vantage point atop the theater where she mysteriously appears out of the ether. …

“Thurston’s quiet finesse on the stage is still apparent. He is a great showman, as his presentation of his legerdemain demonstrates. His suavity, patter, certainty, attitude toward the younger element in his audience point out the reason, not for his success, but for his personal popularity. His following is legion.”

Thurston tapped into spiritualism

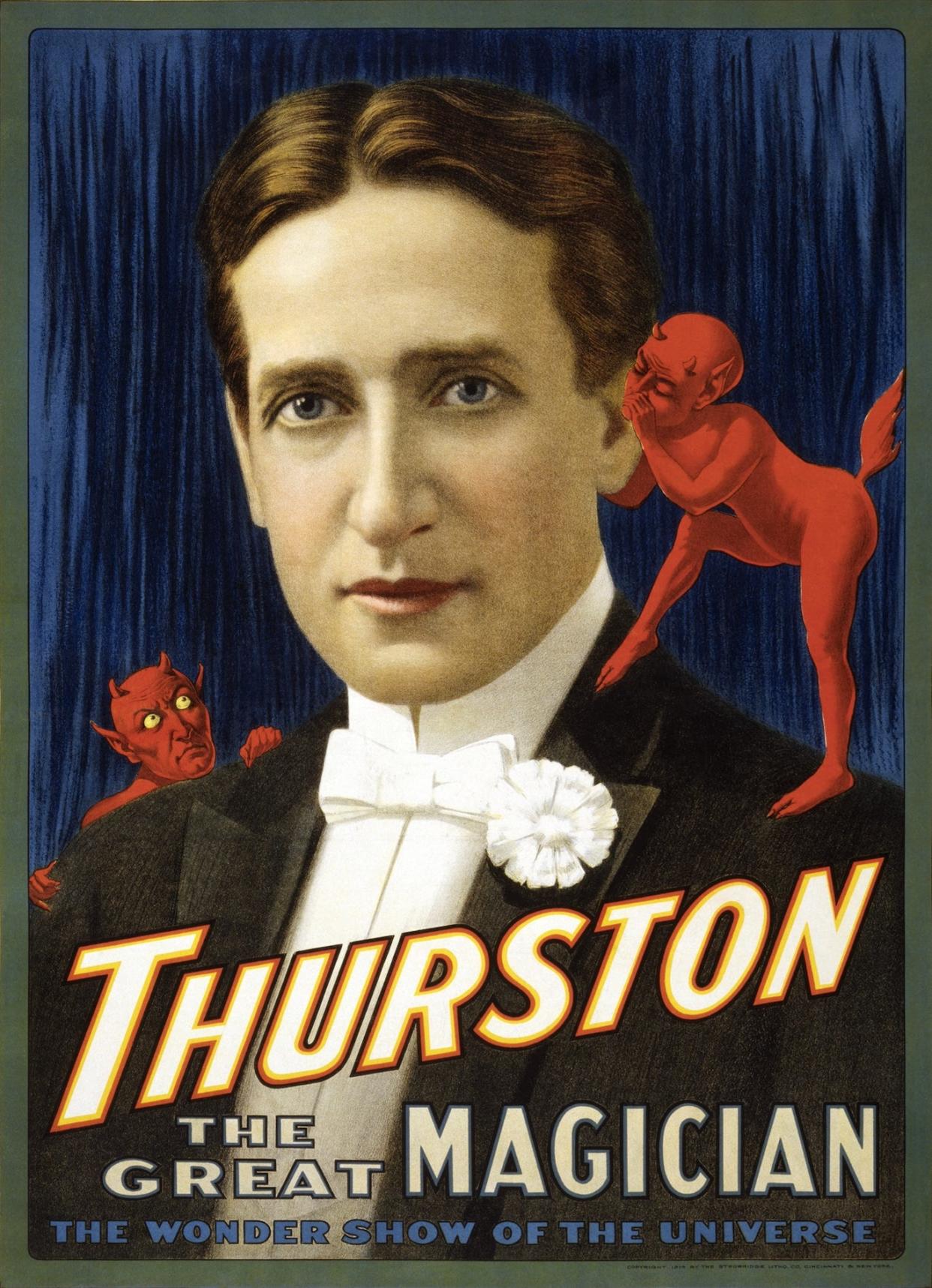

Interest in spiritualism, the belief that psychics and mediums could communicate with the dead, grew following World War I. And Thurston’s act played up to that, suggesting that spirits caused women to levitate, for instance. His posters depicted little devils whispering to him, with the slogan, “Do the spirits come back?”

While Houdini was vocally critical of spiritualism, debunking mediums’ parlor tricks, Thurston took a more nuanced view. At a debate between Thurston and a spiritualist at Carnegie Hall in 1922, The New York Times reported, “The magician said that in his estimation there was ‘an intelligent psychic force which can manifest itself,’ but that ‘everything done at a stated time and for money’ was apt to be trickery.”

Collectors Weekly’s Hunter Oatman-Stanford wrote, “Thurston was aware of the profit to be made by exploiting the murky realm of religion, mysticism, and the supernatural.”

Even as Thurston opened every show saying, “I wouldn’t deceive you for the world,” he knew the veil of mystery was key to the entertainment.

Would Thurston’s spirit return?

Stage magic lost popularity with the emergence of Hollywood. While Houdini was immortalized on film, Thurston was soon forgotten.

He suffered a stroke, then died from pneumonia April 13, 1936, in Miami. He was entombed at Green Lawn Abbey mausoleum in Columbus.

Every year on the anniversary of his death, his friend Claude D. Nobel returned to Thurston’s grave with his magic wand to keep an “after-death pact” in hopes the great magician’s spirit would communicate by vibration.

Cincinnati Post columnist Alfred Segal, writing as Cincinnatus, replied: “But, if Thurston’s ghost didn’t come back, this incident does evoke happy memories among middle-aged people who used to take their children to the Grand on Friday nights when Thurston was there. Oh, that was a great time.”

Sources: “The Last Greatest Magician in the World” by Jim Steinmeyer, “Nothing Up My Sleeve” by Howard Thurston, “The Magician Who Astounded the World by Conjuring Spirits and Talking with Mummies” by Hunter Oatman-Stanford (Collectors Weekly), “Howard Thurston, the Magician Who Disappeared” by Eliza McGraw (Smithsonian Magazine), thurstonmastermagician.com, Enquirer, Cincinnati Post and New York Times archives.

This article originally appeared on Cincinnati Enquirer: The tale of 'The World’s Greatest Magician' who vanished from history