New pretrial release law causes concern over Asheville jail overcrowding, burdened courts

ASHEVILLE – A new law changing how conditions of release after arrest are determined is causing concern among some experts over jail overcrowding and an over-burdened justice system.

North Carolina House Bill 813, dubbed the “Pretrial Integrity Act,” places the responsibility on elected judges, rather than appointed magistrates, to set pretrial release conditions for a slew of more serious charges, including statutory rape and sexual offense, arson and human trafficking. In total, the new law outlines 18 violent offenses that will now require judicial review, meaning a magistrate will no longer be allowed to set these bonds.

“North Carolina law has long recognized that in crimes of domestic violence a 48-hour custody hold pretrial can prevent violence and reduce recidivism,” District Attorney Todd Williams told the Citizen Times earlier this month.

“HB 813 centers these public safety concerns by expanding the 48-hour hold to the most serious crimes of violence ― murder, rape, robbery, arson etc. ― and will give prosecutors and law enforcement sufficient time to contact survivors and advise of them of their Constitutional right to be heard in an open court proceeding in front of a district court judge rather than a magistrate in the Buncombe County Detention Center,” Williams added.

Magistrates are independent judicial officers, as well as officers of the district court, who have various duties in civil and criminal cases, including issuing search and arrest warrants and conducting initial appearances. Supervised by the chief district court judge, a magistrate serves an initial term of two years after being nominated for office by the clerk of superior court and appointed by the senior resident superior court judge. Judges are elected by the voters in their district, with district court judges serving a term of four years and superior court judges serving eight years per term.

However, the law has implications for those arrested on non-violent, less serious crimes as well. Oct. 1, when the law goes into effect, individuals arrested on any non-Class 20 vehicle-related charge while on pre-trial release for any other non-vehicle related charge — meaning their first offense is at any point in the judicial process, from before their initial hearing until before the final verdict — they could spend up to 48 hours in jail waiting for a judge to determine their release conditions. If a judge is not available after 48 hours, a magistrate will set the terms of their release.

“It’s a time and accuracy balance,” N.C. House Rep. Eric Ager, whose district covers East Asheville and Eastern Buncombe County, told the Citizen Times July 19 when asked about the benefits of the new law. “Judges are more accountable and are more experienced in the legal system than magistrates, but they are not available every second of every day like magistrates are generally available.”

More crowded jails?

Ager pointed out that if someone is charged on a Friday night, they will be in jail through the 48 hours because no judges are available to set their release conditions over the weekend. He added that Buncombe County and the rest of the state will “have a lot more people in the jails, and this bill doesn’t do anything to relieve the burden on law enforcement who are managing most of these jails.”

The Buncombe County Sheriff’s Office, which runs the county jail in downtown Asheville, has had issues maintaining detention facility staff, according to previous Citizen Times reporting. In 2021 there was a 125% turnover of detention center staff. As of the afternoon of July 27, the Buncombe County Detention Facility has 395 detainees in custody, according to an online inmate database from the sheriff's office. The main facility and annex can hold 604 detainees per the jail inspector and N.C. Division of Health and Human Services, according to Aaron Sarver, spokesperson for the sheriff’s department.

More: After 125% turnover in 2021, Buncombe approves hourly wage raise for jail staff

When asked how many additional inmates the facility can hold before more staffing is needed, Sarver estimated that if they see the number of detainees reach above about 490, they will need to open additional housing units, which would require between three to five more detention officers per shift. Sarver added that the number of female detainees is more of concern than the total prison population currently, and additional housing units for women are needed.

“We are going through a crisis in our state and local government agencies right now as far as employment and filling those jobs,” Mecklenburg County Sen. Mujtaba Mohammed told the Citizen Times July 19, pointing out the lack of adequate staffing in county jails. “You’re going to continue to see staffing shortages, but now you’re going to have more people there because they have to sit there for 48 hours before a judge is available.”

Lindsey Prather, house representative for south and southwest Buncombe County, voted against HB 813 both times in the House and told the Citizen Times that she believes the impact of switching the responsibility of determining pretrial release conditions from the magistrates to a judge “will be a slower, more overburdened justice system.”

“This bill feels a lot like other bills that have come through this session where one or two cases of a problem crop up, like a violent offender bailing out, and an entire state law is written to combat it,” Prather added. “If we have issues with individual magistrates setting low bail, we should deal with those individuals.”

Sen. Mohammed reflected similar concern regarding an overburdened court system, pointing out how courts are “already stretched thin” and have limited resources and time.

“My concern is that you would want judges to pay attention to the most violent criminal offenses and those individuals with the highest needs, but now you’re going to have judges – while they’re dealing with murder, robbery with a dangerous weapon, violent sex offenses – now they are also going to have to deal with very minor, petty things that I would think we wouldn’t want individuals focused on with our limited resources,” Mohammed added.

Under the current law, where magistrates set the terms of release for all charges other than capital offenses, Buncombe County already has a backlog of over 40 murder cases, partly due to turnover in the district attorney’s office.

Court backlog: 40 murder defendants waiting to be prosecuted; 'stretched' Buncombe DA asks AG for help

Jail shootout: No charges for deputy involved in gunfight in downtown Asheville jail: Buncombe DA

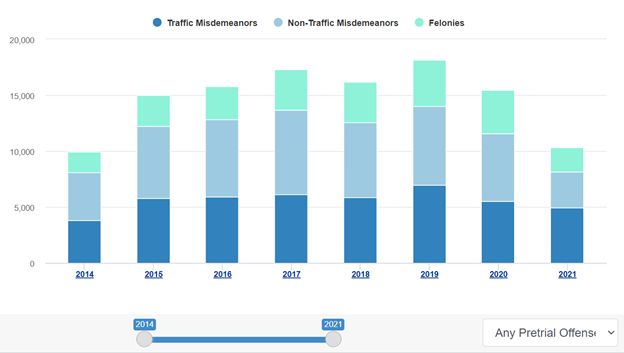

In 2021, there were 5,405 pretrial criminal charges in Buncombe County that would now have to be seen by a judge under this new law, according to data from the UNC School of Government. The number of non-vehicle related pretrial criminal charges in 2021 was much lower than in years past, with 2020 seeing about 10,000 pretrial charges and 2019 seeing about 11,000 pretrial charges that fit the category of judicial review. In 2021, non-traffic misdemeanors accounted for over 31% of all pretrial criminal activity in Buncombe County, with just over 1,000 more charges compared to pretrial felony charges.

“I’ve represented struggling families and parents who have shoplifted diapers for their children, for example, and then have turned around because they don’t have transportation and have been arrested for failure to pay fare,” said Mohammed, stating that people struggling with financial, mental health and substance abuse issues are going to be sitting in jail longer with this new law.

“It’s important for folks to understand that incarcerating individuals, especially for low-level, non-violent criminal offenses, will have severe repercussions in our communities, like losing your job, losing your housing, which reduces public safety for all of us,” Mohammed added. “We’re punishing people before they’ve even been convicted or had their day in court for trial.”

Ryley Ober is the Public Safety Reporter for Asheville Citizen Times, part of the USA Today Network. News tips? Email Ryley at rober@gannett.com. Please support local, daily journalism with a subscription to the Citizen Times.

This article originally appeared on Asheville Citizen Times: new pretrial release law causes concern of Asheville jail overcrowding