‘Pretty personal’: How the politics of health care could affect the midterm elections and control of Congress

Hunter Sego was at a CVS recently in Greencastle, Indiana, when the 26-year-old graduate student did a double take: The cost of filling his insulin prescription and test strips totaled $1,800.

“He goes: ‘Mom, this cannot be right. We have insurance, right?’” his mother, Kathy Sego, recalled. “And I go: ‘Yeah, that’s normal. Go ahead and pay for it.’”

The Segos have been struggling with the soaring cost of insulin and diabetic supplies since Hunter was diagnosed at age 7 – especially with a high deductible on their health insurance. Hunter, who calls the price “absolutely asinine,” has rationed his insulin in the past to stretch out his supply.

So when Kathy Sego saw GOP lawmakers this summer block an effort to cap insulin costs for those on private insurance, the former registered Republican decided that was enough: She would vote Democratic this fall.

"I just don’t want to be so political, but this is not the Republican Party that I grew up with,” she said. “If you’re a Republican and you’re going to vote for (lowering insulin costs) and I know you’re going to vote for that – by gosh – I’ll vote for you.”

Although polls suggest the economy, abortion and crime remain top of mind among many midterm voters, health care remains a motivating issue for some voters, like Sego. In several battleground states, the question could help determine whether Republicans wrest back control of Congress or whether Democrats expand their narrow grip.

Democrats hold a commanding lead – 51%-27% – among voters who prioritize health care, according to a Pew Research Center survey released Oct. 20. The problem for the party in power is that other issues – inflation, the economy, gun violence, abortion, immigration and climate change – all rank as higher concerns among midterm voters, a recent Reuters/Ipsos survey shows.

Though inflation does dominate voter headspace, health care is still a top “second tier” issue to voters, said Bob Blendon, a professor of health policy and political analysis, emeritus, at Harvard University's T.H. Chan School of Public Health.

It might be hard for most voters to isolate rising health care costs when the price of other daily necessities such as food, gas and utilities has skyrocketed in the past year. And when they do, it's all about the effect on their bank accounts, Blendon said.

“They are not interested in long-term problems. They’re talking about high prices of doctor charges and pharmaceuticals,” he said. “Everything is very short-term, and that’s true about the health care cost issue. People are worried about paying their bills in an inflationary time."

Democrats’ health care advantage might not save their majority

When Congress passed the Inflation Reduction Act in August (a slimmed-down version of President Joe Biden's Build Back Better proposal), the White House touted victories on health care:

As many as 7 million Medicare beneficiaries could see their prescription drug costs drop beginning in 2026 because of the provision allowing Medicare to negotiate prescription drug costs.

Pharmacy costs for some of the 50 million Americans with Medicare Part D will be capped at $2,000 a year. That would directly benefit about 1.4 million beneficiaries each year who pay above that amount.

About 3.3 million Medicare beneficiaries with diabetes will benefit from a guarantee that their insulin costs are capped at $35 a month.

About 13 million Americans will continue to save an average of $800 a year on health insurance premiums through the extension of Affordable Care Act subsidies.

The administration estimates an additional 3 million more Americans will have health insurance.

All of that might not matter, said Jarrett Lewis, a pollster at Public Opinion Strategies: It’s a lot harder to campaign on legislative victories such as the Inflation Reduction Act than obvious price differences at the grocery store and the pump.

“It’s tough to sell legislative wins when there’s just so many other things going on right now,” Lewis said.

And relief from the act isn’t immediate: The insulin cap for Medicare patients won’t take effect until next year; the $2,000 cap on pharmacy costs doesn’t kick in until 2025; and Medicare won’t start negotiating lower drug costs until 2026.

Wendy Rzasa, 51, an independent voter from West Lebanon, New Hampshire, isn’t buying what Democrats have to offer.

Rzasa is suffering from long COVID-19 after being diagnosed in January 2021.

“It got my heart, it got my lungs, it got my brain, my whole body,” Rzasa said. “I can give my dog her medicine and forget that I gave it to her. Two minutes later, I don’t have a memory. I can’t read for more than 15-20 minutes.”

She was a medical assistant but was let go because she can’t do direct patient care anymore. Now she pays monthly for COBRA costs to keep her health insurance from work. It costs her $874 a month – almost half of her $1,874 disability check. And her illness forces her to sleep with a CPAP machine that provides her oxygen, which only further raises her electricity bill costs.

Combined with rent, she can’t keep up. She’s going to food pantries now when she never had to before.

She attributes her health costs to overall inflation – and blames the Democrats.

Rzasa plans to vote for Republican Don Bolduc in New Hampshire’s competitive Senate race. Republicans have been eager to flip incumbent Democrat Sen. Maggie Hassan’s seat red on their road map to reclaiming the Senate majority.

"I vote either way. I voted Democrat before, too," Rzasa said. But after seeing two years of full Democratic control in Washington, she's voting for Republicans to change things up.

"The electric bill right now, it's ridiculous," she said.

Races for governor also carry health care implications

The battle over health care isn’t being waged only on Capitol Hill.

When Democrats passed the Affordable Care Act in 2010, states were promised millions in federal aid to expand Medicaid programs for lower-income Americans. Most states took the federal government up on its offer, but 12 mostly Republican-led states have yet to do so, leaving more than 2 million Americans without coverage. (The dozen includes Wisconsin, which hasn't expanded Medicaid but has no coverage gap because its Medicaid program already covers all legally present residents with incomes under the poverty level.)

Costs force rationing: More than 1.3M Americans ration life-saving insulin due to cost. That's 'very worrisome' to doctors.

Expanding access: Biden's COVID-19 relief bill includes an expansion of Obamacare. Here's how it would work

Another of those dozen is Alabama, where Callie Greer said the “Medicaid gap,” as it’s called, cost the life of her daughter, Venus. Her lack of insurance meant she couldn’t get a mammogram to detect the breast cancer she didn’t realize was spreading within her.

One day, though, while sitting in the emergency room on another one of her visits, a doctor walked by her and smelled something awful. Venus lifted her shirt to show the doctor her breast.

“It was literally rotting off,” Greer said, choking back tears. “They sent her to a cancer center in Montgomery. She had Stage 4 cancer, did chemo and radiation. She went back for a six-month checkup, and the cancer had spread to other parts of her body.”

Venus died in Selma in February 2013 after one of two brain tumors burst.

Nearly 10 years later, Alabama has yet to expand Medicaid. GOP Gov. Kay Ivey is a solid favorite to win reelection Nov. 8 in the deep red state, and Republicans are expected to maintain their supermajorities in the state Legislature,

Greer, who now lives in Montgomery, told USA TODAY she's supporting neither Democrats nor Republicans but instead focusing on each candidate. And health care is front and center for her.

“To me, this is the fight, because if you’re not healthy, how do you work and how do you take care of your children, do all the things you’re supposed to do?” Greer said. “My daughter literally died because of this.”

The number of states deciding to expand Medicaid might grow by one this fall.

In North Carolina, House and Senate Republicans this summer reversed longtime opposition to join Democratic colleagues in backing expansion. The House and Senate passed different versions of expansion in June, but all 50 Senate and 120 House seats in the state will be up for grabs Nov. 8. The new Legislature then will decide whether to send an expansion bill – and what that legislation will look like – to the governor for his signature

“North Carolina is a swing state, and this election matters because it’ll determine how Medicaid is going to look like in our state,” said Maya Nair, senior at the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill and a Raleigh-Durham Fellow at the women’s political advocacy organization IGNITE.

More than 1.6 million of the more than 2 million Americans in the coverage gap are in North Carolina, Florida, Texas and Georgia, the latter three of which have gubernatorial elections this year.

Students on the cusp of losing Medicaid insurance on their parents’ plans when they turn 21 are particularly vulnerable, advocates say. And income from work-study programs or excess money from student loans transferred into their bank accounts to help with living expenses, for example, can affect Medicaid eligibility in states without expansion.

“A lot of millennials don’t understand until they’ve lost their insurance,” Nair said.

Even though North Carolina isn't Alabama, Greer realizes every win is a step further. "I may get two victories and 25 losses, but I've still got two victories," she said. "You've got to eat this elephant a bite at a time."

Hot topics: With the midterms two weeks away, what are candidates talking about in political ads?

Ever-rising health care bills: More inflation is on the way, and your health care bills are set to rise. Here's why.

SUBSCRIBE: Help support quality journalism like this.

In Florida and Nevada, retirees grapple with the high cost of staying healthy

Even having government health insurance is no guarantee of affordability.

Burt Scholl, who is 90 and lives in an assisted living facility in Lantana, Florida, found that out when he had cataract surgery recently.

The retired municipal worker who hails from New York describes his living situation as “fortunate,” especially when it comes to his Medicare coverage. But his plan barely fell short on the eye operation. He now faces a hospital bill of $7,500 he'll have to cover completely.

“I discovered to my distress that Medicare only covers a small fraction of the cost of cataract surgery, and so I’m facing a whopping bill now," he told USA TODAY.

It's why health care is the biggest motivator behind Scholl’s vote in the midterm elections.

“I’m not happy about much of the politics here and that politics has unfortunately impacted the health care that is afforded to many people who are in need of it,” Scholl said, noting he is included in that group. “That distresses me a lot.”

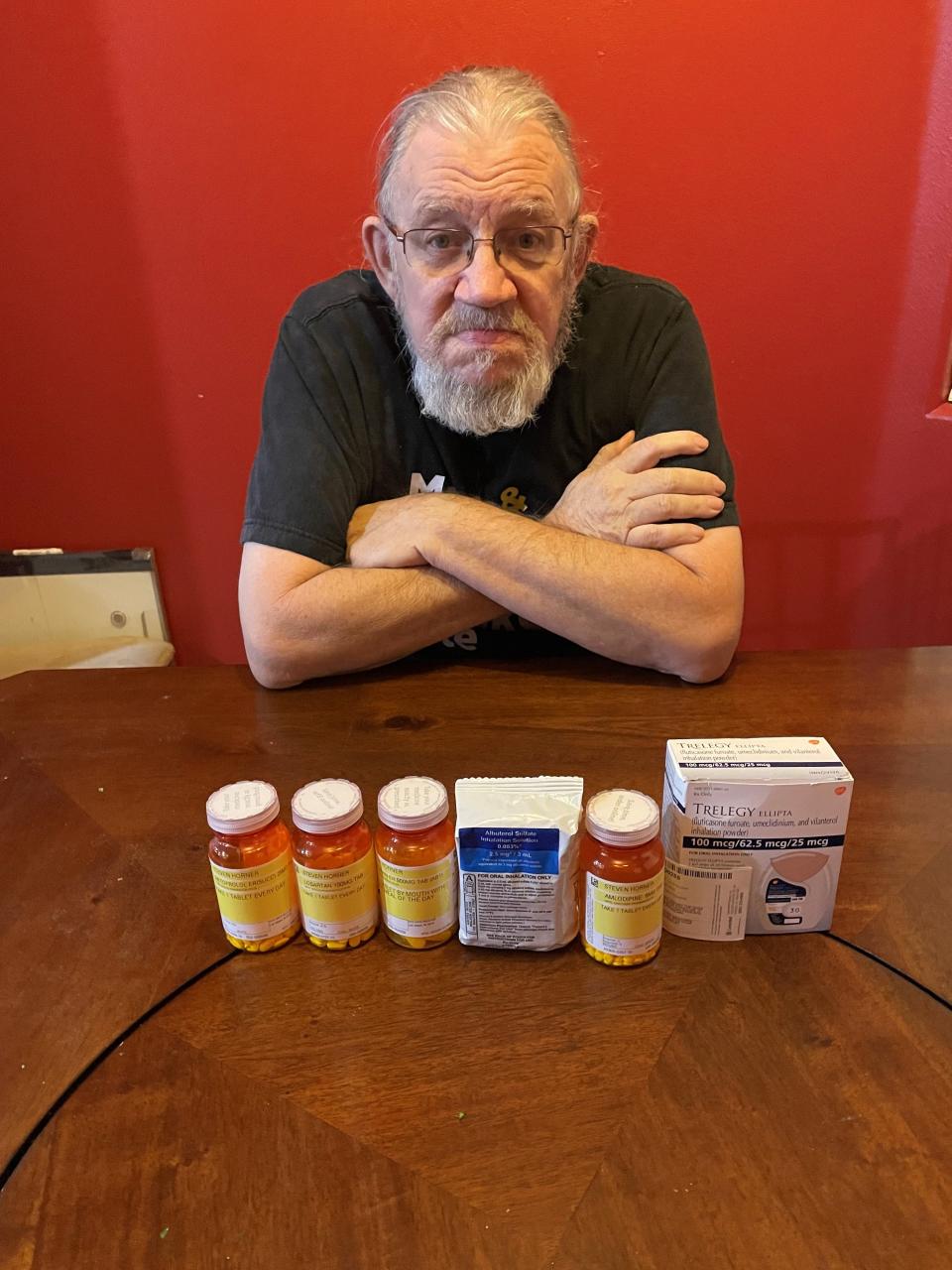

Steven Horner, 71, considers himself “lucky” despite spending nearly $4,000 on out-of-pocket medical costs in 2021 because through his pension and Social Security payments he can afford supplemental insurance along with Medicare, which offset some of his medical costs.

“This isn’t just about me,” said Horner, an Army veteran and retired public school teacher from Las Vegas. “I have heard stories and witnessed stories of people who cannot afford their medication, who cannot afford their insurance, cannot afford the basic health care I believe should be universal.”

Traveling through his home state of Nevada as an advocate for other seniors facing health challenges, Horner witnessed more voters interested in the November elections than he has in a while. Yes, it’s about inflation and abortion rights, he said, but also about health care costs.

Horner, a lifelong Democrat, is more motivated this election cycle because he doesn’t think government is working fast enough to address rising health care costs.

As he considers his vote in a few races, Horner knows he will be voting for Democratic Sen. Catherine Cortez Masto and Democratic Rep. Susie Lee – both rated as toss-up seats – in part because of their support of Biden’s legislation to cap pharmaceutical costs and extend the Affordable Care Act.

GOP: Insulin cap on private insurers part of Democrats’ ‘socialized medicine’ agenda

When it comes to health care, the GOP has given the opposition talking points over the past decade with their flat opposition to enactment of the Affordable Care Act (also known as Obamacare) and their relentless – but unsuccessful – efforts to repeal it.

Earlier this year, Florida Sen. Rick Scott, head of the campaign arm of Senate Republicans, called for requiring all federal legislation be renewed every five years, including entitlement programs. Democrats accuse Republicans of wanting to “sunset” Social Security and Medicare. Scott has said he wants to “fix and “preserve” those programs, without providing details.

Then came the largely party-line vote in August to strip out of the Inflation Reduction Act a provision capping monthly insulin costs at $35 for private insurers. (The act does include a $35 cap for Medicare patients.)

Republicans argue that insurers would have raised premiums to compensate for the loss of revenue from capping insulin. In addition, they argue the insulin cap is part of the "socialized medicine" agenda Democrats are pushing that will ultimately lead to higher costs for consumers overall.

"Today, it's the government fixing the price on insulin. What's next? Gas? food?" Washington State Rep. Cathy McMorris Rodgers, top Republican on the Energy and Commerce Committee, said on the House floor in March. "History tells us that price fixing doesn't work. It shifts the problem someplace else so the powerful has the excuse for more subsidies, more spending and more control."

Kristin Thompson-Lerberg, who's from Holmen, Wisconsin, and has diabetes, said she could use some relief.

“Things are a little bit scary,” said the 42-year-old high school English teacher. “Specifically with regard to insulin costs and diabetes care.”

At her home, she uses insulin, an insulin pump and a continuous glucose monitoring system that constantly reads her blood sugar levels. That all runs about $500 a month.

“Sometimes I don’t really know what my insurance pays for,” Thompson-Lerberg said.

She has been paying attention to local state and national politics. In both, she saw Republicans block a $35 co-pay cap on insulin for private insurers, which was enough to persuade her to vote for Democrats this year.

She’s voting for Mandela Barnes in Wisconsin’s Senate race against GOP incumbent Ron Johnson, a tight race that could determine which party controls the Senate next year. She’s a Democratic-leaning independent but says she has seen enough on what Republicans have to offer when it comes to health care costs.

“For me, that’s pretty personal. They had an opportunity to curb the cost for diabetics and they chose not to,” she said.

Paying for health care: ‘You squeeze one side and it just comes out the other’

GOP lawmakers, led by House Leader Kevin McCarthy, have threatened to repeal the Inflation Reduction Act if they win control of Congress in November – not so much for its health care provisions but for a provision restoring 87,000 agents, clerks and tax assistance positions to the IRS.

Still, the result of repeal would be the same: an elimination of health care benefits for millions of Americans.

"Health care is such a key issue, in the past, that senior voters have decided election outcomes based on threats to overhaul Medicare or to raise Medicare costs,” said Mary Johnson, policy analyst at The Senior Citizens League and a senior herself. “Older voters will vote against candidates whom they perceive as threatening their pocketbooks.”

Seniors are famously the most reliable voters. In the last midterm election in 2018, their group turned out the highest percentage of voters. Sixty-six percent of voters 60 and older cast ballots, followed by voters ages 45 to 59 with 56% according to AARP. Bringing up the rear were those ages 18 to 29 with 33%.

These are all important issues to seniors, but few people are paying attention, said Jenny Chumbley Hogue, an insurance broker near Dallas and an analyst at medicareresources.org, which helps seniors navigate the program.

“I think incumbents will need to show older voters what legislation they have supported will be worth to them,” Johnson said. “I think they need to show voters their records on how they protect beneficiaries from higher costs.”

Even so, skepticism runs deep. “Prescription caps will be helpful, but I guess it just depends on how all this is being paid for,” said Gillian Forsyth, a small-business owner who is over 50 and needs insulin for her diabetes. “It's like a balloon. You squeeze one side and it just comes out the other. I am always pretty skeptical when it comes to anything political.”

For those who have been paying attention and have an opinion, though, “we are reminding Congress that seniors are a huge part of their voting block!” Johnson wrote in a Facebook comment in September to her fellow seniors.

Lessons learned: I didn't vote in 2016. Young, liberal voters: Don't make my mistake with the midterms.

Voting access: Pennsylvania is about to vote. Here's what to know about voting and ballot access in 2022

This article originally appeared on USA TODAY: Insulin, drug prices: How healthcare could decide control of Congress